NorthBay biz checks in with local real estate and mortgage agents for an update on the housing market.

“In the upper end, homes priced at a million-plus, the activity’s been surprisingly good,” she says. “We’ve seen a lot of people coming in from out of state and out of the county, buying second homes, retirement homes—with all cash.” She smiles at our lifted eyebrow. “Yes, all cash! Getting loans these days can be difficult.”

There, in short, is the good and the bad of it.

Ask anyone in real estate, and they’ll tell you it’s a great time to buy. But whether you’ll be successful depends on who you are, where you’re looking and how much time you have. If you want to sell, that’s another story entirely.

What’s selling where?

“In risky markets,” says Eric Drew, owner of two Sotheby’s International Artisan agencies—one in Fountaingrove and one in Healdsburg—“money goes toward quality and scarcity.” Healdsburg, which is nestled in Wine Country, with a small-town, agricultural feel and reasonable proximity to a major city, excels on both counts. “Being a slow growth town, we have a high ratio of quality and scarcity.”

A typical client, he says, is coming for the quality of life. “I had a lady call today who’s 53, was raised here, went off and raised her family and had a career in New York, and is now thinking of coming back. When that’s your story, you don’t come back to Santa Rosa or Cloverdale. You come back to Healdsburg.”

Or, you go to the city of Sonoma, as Bill Dardon would say, easing back in his chair at the desk he’s occupied for 15 years at The Real Estate Company, a friendly, 24-year-old office with green shutters that looks out onto the lawn of the Plaza. “Sonoma,” he says, “is still one of the best places to invest your dollar.”

Over in West Marin, in the idiosyncratic town of Bolinas, known for its dim view of outsiders, broker Flower Fraser of Seashore Realty wishes she could see a few more of them. “We’re having a very sluggish year,” she says. “There just aren’t many buyers.” The little town, with its fiercely defended building moratorium, has scarcity and unparalleled coastal charm. But right now, if prices seem to be holding, it’s because owners are holding on to them. “We have listings,” says Fraser, “but the sellers are holding on to their asking prices. They don’t seem to be very motivated in this market.”

Claudia Coury, director of marketing at Frank Howard Allen Realtors in Marin County, agrees. “Unfortunately, even with the barrage of information that’s been out for the last couple of years about the economy and the housing market, some sellers are resistant to price at the market rate!” They can do it, if they don’t have to sell.

“If you don’t have to sell, it’s probably a good time not to sell,” says Wendy Lynch, a real estate adviser for Prudential California Realty in Napa Valley, where the prices range from the extreme high end to blue collar communities. Across the spectrum, what everyone wants to know is: Is it time to buy? Is time to sell?

For every neighborhood and for every price range, the answer may be different.

Location, location, location

Jeff Lester, an agent for Artisan Sotheby’s International Realty, learned his real estate philosophy from his grandmother, who prospered in real estate in Coastal California. Buy low, sell high, she taught him, and remember the real estate cycle is slow and predictable. As a student of cycles, Lester rates all areas on an A, B or C level. Homes in the “C” level, which he describes as “not really great homes or in great locations,” would be in the $500,000 and under range. Homes in the middle-of-the-road, “B” level areas would be in the $500,000 to $1 million range. “A” level homes are priced from $1 million and up. “When you’re in an “A” area, or an “A” home, you can feel it,” he says. “It makes sense. It’s just right, all the way around.”

In a downturn such as we’ve just experienced, the “first wave” of distress is always in the lower price range, the “C” level, where people acquired homes thanks to the lending policies. As rates rose or they lost their jobs, they couldn’t afford them and the banks foreclosed. Then the cycle works its way into the “B” area, where people can usually hold on a little longer, perhaps because they have more equity or still have their jobs and maybe better advisers.

In the “A” range, the upper end, there’s a surprise. “The myth,” says Lester, “is that ‘A’ level homes are never affected, or that the cycle won’t get to them. Then it does! But those people have the most ability to hold on to their properties longer. They have better consultants; they have attorneys and financial advisers who can help them. But some got caught up in the overpricing, too. So you do have foreclosures and short sales at this level—you just don’t have as many.”

According to Lester, that’s where we are now. We’re in the last phase before we go into stability, something he doesn’t foresee happening for three to five years.

The dreaded other shoe

Brian Connell, broker/manager of Frank Howard Allen in Santa Rosa, says he sees a trend toward stabilization in the low- to middle-price ranges, with prices still soft in the mid-upper to upper-end range. But, he notes, the deflation has lowered the price bar so that now, mid-upper is “anywhere from $600,000 on up the ladder.”

Higher-priced properties have taken longer to show stress, but now it’s starting to happen. “The nature of the real estate market is, you just have fewer buyers in the upper end than in the lower end. Now we’re starting to see some foreclosures in the upper end.

“The big question everybody’s asking is whether there’ll be another shoe dropping with distressed properties and/or mortgages. And I think the best answer we have is that it remains somewhat uncertain. We believe that, with the historically low financing, the low mortgage rates driving demand and with an improving job situation—but not improved enough to really lend support to our market—we’re going to have another 24 to 36 months of dealing with distressed properties [short sales and foreclosures] in this mid-to-lower bracket.”

This means those needing to sell will probably still be suffering, and with properties going at bargain rates, at least in those categories, buyers should be ecstatic.

So who’s buying?

Lester sees a pyramid. “On the top level, we have sort of an elite, astute bunch of people, sort of like my grandma, who actually are quite well-to-do and know a lot about real estate, and those folks are bargain shopping,” he says. “For the first year or so, they weren’t participating at all. But recently, they’re seeing significant price drops in the very large, very nice ‘A’ properties, and they’ll say, ‘Hey, I can buy this 300-acre parcel with three houses on it for $2.2 million right now—and those were selling for like $6 or $8 million during the boom. These are bargains.’ So that segment is coming out and buying.”

“Smart money is back!” says Connell. “Investors see things going down and come in, sometimes with cash. We see investors from all over the place making offers on all categories, whether on luxury price points or down in the starter-home area. Buyers are willing and able to close on escrows if there’s true value reflected in the property.”

The consensus is that it’s a great time to buy. “If you have everything aligned right now, you have motivated sellers, low prices and low interest rates—what else could you ask for?” says Ken McCoy, branch manager at Petaluma Home Loans. “Those are the three things you’re always looking for, so why wouldn’t it be a good time to buy?”

Lenders, lenders, lenders

“If anything is holding all of this up from being a good market,” says Lynch, “it’s the banks and the lenders. You have to be overly qualified, and they’ll run a credit check the day before closing to make sure you’re still the person you said you were.”

Houses in this market—the short sales, the REOs—are priced to sell, explains Debby Benson-Miller, an agent with Prudential California Realty, like an auction or fire sale. The point is to get as many offers as possible, pick the highest and

unload the property, retaining as much money as possible for the bank. [A “short sale,” for those who haven’t kept up, is a seller’s alternative to foreclosure. The bank gets something as opposed to nothing, and the owners walk away, still liable for the unpaid amount, but without the lethal word “foreclosure” on their credit report. An REO, or real estate owned, is a foreclosure.]

There are deals to be had in all price ranges. “If you’re looking at the REO market in Sonoma Valley,” says Bill Dardon, “there are 21 [at this writing] that are either short sales or REOs. There’s one for $1,355,000—and that’s a short sale. Can you imagine?” This is less than last year and the year before. “When we started this craziness, we had about 190 total inventory, and 30 of them were short sales.”

In the lower end, buyers seem to be swarming over each new short sale or REO, presenting multiple offers with all cash or impeccable credit, and still the deals take forever to close. “I’m seeing a lot of buyers in that $200,000 to $275,000 range,” says Benson-Miller. “There’s a lot of competition in that range, mostly first-time homebuyers, not all investors, but with all the foreclosures and short sales, everything is taking longer.”

“I have buyers out there who’ve been putting in offers for six to eight months and haven’t gotten one yet,” adds McCoy, explaining that most properties receive multiple offers or, in the case of short sales, it can often take a bank months to approve an offer (or even respond).

Liz Smith, a legal secretary working for a firm in St. Helena, can vouch for that. She was looking for a bargain house for her grown son, in Vallejo, and for every house her realtor showed her, there would be 12 offers already ahead of them. She and her husband finally signed up for email alerts and changed realtors to one who was located in the same city and worked full-time as a realtor. When she did succeed in closing on a house, it was because she had great credit, determination—and time. The house she wanted had been purchased for $440,000 and the bank was selling it for $135,000. Her realtor advised her that, since it’s “a frenzy,” to offer more. They offered $145,000, and the bank accepted, but it took months to close. “The banks are looking at everything and being more stringent than they normally would,” she says. Buyers have to compete hard.

Weep not for the banks

The current practice of encouraging the selling of properties for more than the asking price, or even the appraised value, causes some concern. “Sometimes you feel the banks should be held to a higher standard,” says Benson-Miller, “and they’re not.”

She recently closed on an REO, in which the buyer, in order to get the property, ended up having to pay not just more than the asking price, but more than the actual appraised price. “We were up against others,” she says, “so we came in strong. The buyer said, ‘I want to go a little over the asking price to see if I can get this.’ I said I didn’t know where it was going to come out, appraisal-wise, but we checked the appraisal box, meaning the contract would be subject to appraisal. The bank accepted the offer only if we would forego the appraisal.”

The problem with that, she explained, is that the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), which was the loan they were seeking, will only grant a loan based on the appraised price. Buyers who are going for a 3.5 percent down payment FHA loan—“which is most buyers right now”—are doing so because they don’t have a lot of extra funds. “So if the client offers $290,000 and the appraisal comes in at $270,000, then the buyer has to come up with the extra $20,000 if they waive their appraisal contingency, because FHA won’t lend over the amount of the appraisal.”

Benson-Miller told the client she absolutely did not recommend they forego appraisal contingency, and they agreed. “So we went back to the seller, and they accepted the offer anyway. Then the appraisal came in low, and the bank said they wanted us to pay $5,000 more than the appraisal price—which had to come out of the buyers’ pockets.”

Somehow, to her, that seems wrong. “It’s not holding the bank to a higher standard if they can ask you to pay more than it’s actually worth.”

Who determines a property’s worth?

“Appraisals are cash cows for the banks right now,” says Ken McCoy. That’s because, in an attempt to discourage inflation of property values, banks now require mortgage brokers to choose from randomly assigned appraisers from national appraisal companies—which may be owned by the bank. The result is that, unlike the good old days, when the appraiser would be a local who knows the neighborhoods and properties, now, for an exclusive property in St. Helena or Bolinas, say, you may get an appraiser from Stockton, who hasn’t a clue about the area. What’s more, appraisal fees have increased an average of $100 in the last 12 months because of all the new requirements. The process has gotten better over the last year, says McCoy, but there’s still room for improvement.

Wendy Lynch had such an appraisal on a property in Napa. “They said this property is ‘close to a railroad,’ and that’s a ding against the property. But it was the Wine Train! In Napa, trains are different.”

Also, adds Cherniss, the banks can ask for second appraisals, sometimes right before scheduled closing—“in case the value of the property has changed during the time of escrow.” It’s another thing that increases the time and cost of the sale—and the wear and tear on the agent.

The crisis has taken its toll

“Everybody’s been affected by this mess,” says Dardon, “whether you’re rich or poor. Pets Lifeline, the Sonoma shelter, has gotten more strays because people will abandon their dogs and cats because they can’t take them when they move out [because of a foreclosure or short sale]!”

“It’s hard, unless you’re a real positive person,” says Lynch. “The other side of this is, it’s changed our jobs. We now see a lot of people who need emotional counseling and support.”

“You do a little bit of counseling with people,” says Benson-Miller, “because it’s very hard on them. And you have to be very sensitive.” She notes that agents are kinder these days. “People are trying to make things work. It’s like, ‘We’re human beings, let’s do our best to make this happen.’ I would rather someone walk away from a purchase if, in the long run, it’s going to give them problems. You don’t want to encourage people to make bad decisions just to help yourself.”

“I think the people who don’t like helping people have stepped away,” says Lynch. “I’ve heard it said by a lot of realtors: We’re working three times harder to make half as much money.”

The tough get creative

The best managers work hard to help their agents help their clients—and technology is the new best friend. All use the Internet, most have set up individual websites for the various properties, and some raise the website to a level of aesthetic delight. Visiting Eric Drew’s Healdsburg Sotheby International website is an “A” experience in itself. Drew, an amateur photographer, insists on professional photography, and his website draws you in to each home, from high end to modest cottage. The map, a smaller version of the amazing Google real estate map, lets you see what’s selling, where and for how much, and to virtually visit each. He’s recently bought a couple of iPads for his Healdsburg agents, and has oriented them to real estate. “The iPad will be a transformational tool for people in the field,” he says. “It’s great if you’re in a strange town, working with a realtor. The clients understand where they are and what they’re doing.” To him, the best client is an informed client, and he and his agents are dedicated to helping them find the house that works for them.

Words to the wise

Other than getting an iPad or hooking into Google’s real estate map, what advice—aside from the obvious “getting your credit in shape”—resounds out of all of this?

For buyers, “If you’re going to invest, the day of the ‘flipper’ is over,” says Dardon. “You’re going to need to invest your dollars long term, anywhere from five to seven years.”

For sellers, “Listen to your agents,” says Coury. “People will listen to their doctor, their lawyer and their accountant, but they hire a real estate agent and won’t always listen to what they tell them about price. It’s too hard a pill to swallow.”

For everyone, from Benson-Miller, “Real estate is always going to be a part of our life. It’s always been the American dream to own a home. I think we’ll get through this. It just takes patience.”

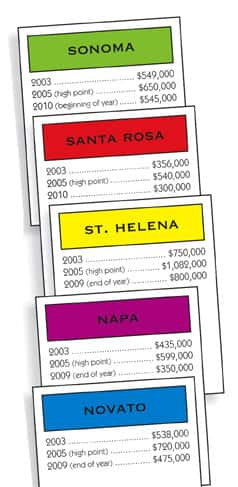

Home Prices at a Glance