SSU economists interpret data regarding North Bay business trends.

The School of Business and Economics at Sonoma State University (SSU) has, as its vision, to be a catalyst for regional economic prosperity. In pursuit of this vision and to support the North Bay’s business development activities, the School of Business and Economics has launched an Economic Development and Innovation Accelerator as part of the North Bay iHub. Its goal is to increase the velocity of economic development initiatives focused on job creation and business growth by aligning existing efforts, and by launching new programs to complete the value chain for regional economic development. In this article, we describe three projects that will help gauge how well the North Bay is generating new businesses, its labor market stability and the means by which new ideas and business get launched and begin to generate high-value jobs.

Regional labor market monitoring

SSU’s School of Business and Economics has produced a regional labor market analysis for the North Bay. Sonoma State’s labor market expert, Dr. Steven Cuellar, has analyzed the latest information from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and the Employment Development Department of California (EDD) and has developed the infrastructure for a regional forecast for labor markets. This data will help those concerned with an economic outlook of the North Bay economy make well-informed business decisions. This is more than just a snapshot of the North Bay economy, as it identifies trends that provide important and actionable insights for existing firms as well as potential firms and entrepreneurs. This detailed analysis looks more closely at each of the six North Bay counties (Lake, Marin, Mendocino, Napa, Sonoma and Solano) and delves more deeply into the sub-sectors of the economy that are driving the economic growth, as well as those sectors that are declining. Additionally, trends among the highest and lowest paying sectors are also identified. The following is an excerpt from the upcoming report.

The Sonoma County labor market

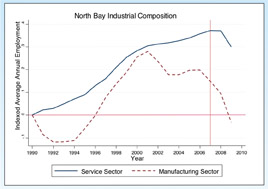

In Sonoma County, private sector employment was approximately 124,564 in 1990 with the service sector employing the majority of workers (approximately 70 percent) or roughly double (2.27 times) what the goods sector employed (86,529 for the service sector and 38,035 for the goods sector).

By 2009, private sector employment had grown to 150,314, with the service sector now making up approximately 76 percent of the labor force. This increase in the service sector share of the local labor force began in 2001 when the goods producing sector began to experience a decrease in employment while service sector employment continued to grow.

While the service sector continues to employ the majority of workers in Sonoma County, service sector earnings on average continue to lag behind that of the goods-producing sector, with average annual earnings in the service sector of $39,386 compared to average annual earnings in the goods-producing sector of $51,239. Analysis of the trend in wages indicates that this difference has not, however, increased over time.

The highest-paying industries (with incomes of more than $60,000 per year) in Sonoma County are currently utilities, professional and technical services, management of companies and enterprises, finance and insurance, public administration and mining. Unfortunately, these are not high-employing industries. Of the sectors paying more than $50,000, only retail trade and health care provide employment of more than 20,000 people.

The industries that employ the largest number of people—retail trade, accommodation and food services, health care and construction—unfortunately aren’t high-paying industries. All except construction, which lost more jobs than any sector during the past recession, pay less than $50,000 per year with accommodation and food services paying less than $20,000.

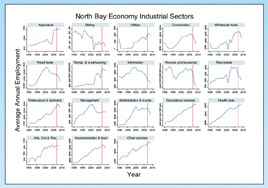

The intersection of high-paying and high-employing sectors in Sonoma County include wholesale trade, information, finance and insurance, professional and technical services, management of companies and enterprises and health care. These sectors can be categorized as growing sectors and shrinking sectors.

Wholesale trade, while losing jobs during the recession, is a relatively high-paying sector, paying more than $50,000 per year, and has been growing since 1995.

Professional and technical services, which lost some employment due to the recession, is another high-paying sector, with average annual income of more than $60,000, and has been growing since 1990.

Health care and social assistance is a relatively high-paying sector, with an average annual income of more than $50,000, and is one of the few sectors that was relatively unaffected by the recessions. It’s seen growth since 1990.

Management of companies and enterprises, with an average annual income of more than $60,000, had seen negative employment growth since 2001 but is one of the few sectors that experienced marginal growth since the recession.

Information, a relatively high-paying sector, with an average annual income of nearly $55,000, is an industry that’s been shrinking since 2001.

Finance and insurance, with an average annual income of just more than $60,000, has seen negative employment growth since 2002.

A closer look (four-digit NAICS)

Examining high-paying sectors at the four-digit NAICS code allows a closer look at which sectors are growing and which are shrinking.

Electrical equipment and manufacturing is a high-paying sector, with an average annual income of more than $75,000, and was relatively unaffected by the recession.

Software publishing is another high-paying sector, with an average annual income of more than $100,000, and has seen resurgence since 2003.

Scientific research, with an average annual income of approximately $135,000, has receded since the recession but had been a booming industry since 1993.

Communications equipment manufacturing, with an average annual income of more than $120,000, has been declining steadily from its peak in 2001.

Electrical instrument manufacturing, with an average annual income of $100,000, was a growing sector throughout the 1990s but has seen a steady decline since 2001.

Medical equipment and supplies manufacturing, with an average annual income of nearly $90,000, has also experienced a steady decline since 2000.

The data reported here are parts of SSU’s ongoing research, which include other counties within the North Bay. The School of Business and Economics will be providing comparisons and analysis for the changes to the North Bay counties and the implications of those changes for the labor force in this region and the types of businesses that may grow and thrive here with that resource.

The North Bay

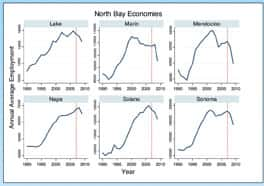

Since its high in employment of just less than 550,000 in 2007, prior to the onset of the “Great Recession” in late 2007, the North Bay economy has lost nearly 36,000 jobs, or about 6.6 percent, of its labor force. While job losses were felt across all six North Bay economies, not all economies were affected equally.

In percentage terms, Sonoma (the largest of the North Bay economies) and Mendocino (the second smallest of the North Bay Economies) experienced the greatest job losses, with each losing 8.6 percent of their pre-recession levels of employment. In terms of jobs lost, that equals 16,606 and 2,820 jobs, respectively. The remaining North Bay county economies fared better: Lake lost 6.2 percent (959 jobs), Marin lost 5.5 percent (6,023 jobs), Solano lost 5.1 percent (6,500 jobs) and Napa lost 4.3 percent (2,949 jobs).

Just as the job losses weren’t felt equally across counties in the North Bay, the industrial composition of North Bay was not affected neutrally. The number of private service sector jobs lost was 18,528, and the number of private manufacturing jobs lost was 16,521. While the absolute number of jobs appears relatively similar, the percentage of jobs lost was roughly three times as great in the manufacturing sector than in the service sector, at 5.2 percent and 15.7 percent, respectively.

Industry-specific studies

Community impact reports (CIRs) have become a requirement or a request of many new projects in the North Bay economy. Some cities, including Petaluma, require a CIR for any new development that goes before its planning commission. These reports provide summary information about the economic, social and fiscal impacts of the expansion or entry of a company into the local market. An environmental impact report (EIR) is a classic necessity for new or expanding companies going before planning commissions and city councils. A CIR provides estimates of net job gains from the new firm, the tax impact on local government, the change in so-called “urban blight,” and many other factors of how a community is affected by a changing business footprint. The CIR and EIR together provide a “three E’s” look at new projects: economic vitality, social equity and environmental balance.

In 2010, the School of Business and Economics performed a CIR for Clubsource, Inc., the owner of Club One Fitness Centers. Clubsource is considering an expansion in the North Bay and wanted to look at the economic impacts: jobs created/sustained by the construction and operations of the club; business revenue generated as a result of construction of a new facility and operations of a new club; and the tax impacts of both these events. The following is a summary of the economic impacts of the construction and operation of that facility, assuming the following:

• A construction project of $25 million;

• 5,000 members (households) served within two years’ time; and

• Each member/household spends an average of $150/month, equaling $9 million in revenue annually.

The construction phase creates more than 114 new jobs in Novato in an industry that’s hurting for new job creation (construction), $860,000 in local and state taxes and $20 million in new business revenue. For ongoing operations, more than 154 new jobs are created in Novato, with annual increases in business revenues and new state and local taxes of $9.1 million and $557,000, respectively.

Such information is just one part of a CIR and other community aspects of entry into a new market can also be explored. For example, Clubsource has looked to partner with local municipalities on providing an extension or a substitute for local parks and recreation to reduce the squeeze on fiscal budgets for maintaining facilities and programs while providing equitable recreation and promoting fitness and wellness in the community. Such additional impacts are the essence of the value of CIRs.

Future research projects

The School of Business and Economics is also monitoring the wine industry in the North Bay, the growing tourism sector and different technological segments. Each of these areas is important because they are export industries, provide a wide breadth of jobs for this region and feed off of each other in terms of how economic and community development interact.

That the North Bay needs a coherent economic development focus no longer seems to be an item to be debated. But there are different visions of what economic development means and how to best build a foundation of sustainable business practices and healthy economic growth. One way to move beyond debate and into action is to recognize that regional economic prosperity begins with smart business decisions based on data. The research projects summarized here are illustrations of the faculty and students at SSU’s School of Business and Economics are supplying the information needed to support data-driven decision making in business and economic development.