NorthBay biz shines a spotlight on the economy and culture of Marin County.

Tucked between San Francisco and Northern California’s Wine Country, Marin County could be just a place on the map for people passing through. Instead, it’s extraordinarily diverse. Among its assets are fishermen who make their homes along 72 miles of Pacific coastline, farmers who’ve brought organic agriculture into the mainstream, artists and inventors working in the shadow of Mt. Tamalpais and sophisticated scientific research that draws attention from around the world. Measuring just 520.31 square miles, Marin County is small but unique; one reason for this, beyond geographic diversity, is that many of its residents tend to think big regardless of the pursuit. Their combination of an adventurous spirit and the gift of innovative thinking make anything seem possible.

Tucked between San Francisco and Northern California’s Wine Country, Marin County could be just a place on the map for people passing through. Instead, it’s extraordinarily diverse. Among its assets are fishermen who make their homes along 72 miles of Pacific coastline, farmers who’ve brought organic agriculture into the mainstream, artists and inventors working in the shadow of Mt. Tamalpais and sophisticated scientific research that draws attention from around the world. Measuring just 520.31 square miles, Marin County is small but unique; one reason for this, beyond geographic diversity, is that many of its residents tend to think big regardless of the pursuit. Their combination of an adventurous spirit and the gift of innovative thinking make anything seem possible.21st century agriculture

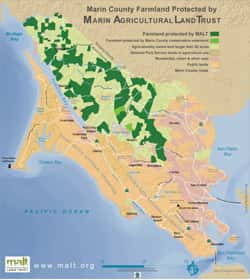

Agriculture is a presence in West Marin thanks to some remarkable vision. In 1980, biologist Phyllis Faber and the late Ellen Straus, concerned about the threat of development and the decline of family farms, founded the Marin Agricultural Land Trust (MALT), a pioneering model that lets farmers sell their conservation easements to the nonprofit organization, thus preserving the land for agricultural use forever. To date, MALT has preserved 73 family farms on 46,000 acres of farmland, almost half the county’s agricultural land. And with more than 20 families also holding leases for agricultural use in the Point Reyes National Seashore’s 18,000-acre pastoral zone, Marin’s rural character is here to stay.

Organic production is at the heart of agriculture In Marin and Sonoma counties, where the majority of dairy farms are certified organic and GMOs are banned. Albert Straus, owner of the Straus Family Farm in Marshall and the Straus Family Creamery in Petaluma, was a leader of the transition to organic practices. After studying dairy sciences at California Polytechnic Sate University, he returned to the family farm in 1977 to work with his late father, Bill. In 1993, he achieved organic certification for the dairy, making it the first farm west of the Mississippi River to earn the designation. The concept was so new at the time that he helped write the regulations. “It’s a model that’s worked out well,” he says, observing that the practices involved respect the land, animals, people, employment and products. With 75 percent of Marin’s dairy farms now certified organic, “It’s no longer a niche market,” he says. “I think it is the way of the future.”

Organic production is at the heart of agriculture In Marin and Sonoma counties, where the majority of dairy farms are certified organic and GMOs are banned. Albert Straus, owner of the Straus Family Farm in Marshall and the Straus Family Creamery in Petaluma, was a leader of the transition to organic practices. After studying dairy sciences at California Polytechnic Sate University, he returned to the family farm in 1977 to work with his late father, Bill. In 1993, he achieved organic certification for the dairy, making it the first farm west of the Mississippi River to earn the designation. The concept was so new at the time that he helped write the regulations. “It’s a model that’s worked out well,” he says, observing that the practices involved respect the land, animals, people, employment and products. With 75 percent of Marin’s dairy farms now certified organic, “It’s no longer a niche market,” he says. “I think it is the way of the future.”Today, Straus’ mission is to revitalize farming and make it sustainable, and his new goal is finding ways to use technology to make it more efficient. “We’re trying to make a new business model for organic farming,” he says. At his farm, each cow has an ID chip, calves drink from a computerized feeder that tracks how much they’re drinking, and computers monitor how much milk cows produce, keep track of how much the animals are eating and determine when it’s necessary to reorder feed (and how much). In addition, a methane digester generates energy from the cows’ waste and uses it to produce electricity and heat water for use in washing milking equipment. Straus is also working on a design for an electric feed truck that’s powered by the cows’ methane waste and says, “The idea is about closing the loop; the cows would power the truck that feeds them.”

The dairy is also using reclaimed water wherever possible. Straus explains that during the drought in 1976, his family had to haul water for nine months, until they found a well. Thus, water conservation has long been a priority. “Water is a very limited resource for us,” he says, so the operations reuse water for flushing down the barns and put it through five different ponds to recirculate it. The recycling accounts for 15,000 gallons of water per day, a substantial amount in water-challenged California. “We close the loop wherever we can,” Straus says.

Straus Family Farm is a Marin Carbon Project demonstration farm. As such, it’s implementing carbon-farm methods, such as applying compost, intensively grazing the animals and promoting growth of the pastures and crops, which, in turn, captures carbon in the soil, preventing its emission, which is healthier for the environment. In addition to the environmental benefits, Straus points out that there’s a potential for farms to get carbon credits, and farmers will earn money from cap and trade. “We’re looking at what we should do in the future,” he says, explaining that, in addition to trying out new methods, they’re showing others how it’s done. “We want to make it an economic model as well as environmentally sustainable. We’re looking at the long-term viability of farms,” he says. He believes the research is important for local farms but that it can have a global impact as well. “It’s important that we’re in the forefront and help mitigate climate change,” he says.

Another key participant in the Marin Carbon Project is Marin Organic, a Point Reyes Station-based nonprofit founded in 1999. Its mission is to promote organic agriculture and provide educational opportunities for farmers and school children. It also helps people with economic challenges gain access to fresh, organic produce through efforts such as National Gleaning Week, which took place in October and included Green Gulch Farm, Star Route Farms and Countyline Harvest. Like MALT, Marin Organic is a model that others emulate. Executive Director Jeffrey Westman says it’s had an impact on Northern California and, to varying degrees, many different parts of the world. He reports 40,632 acres of Marin farmland is certified organic, 42 farms are members of Marin Organic and more than 40 restaurants carry the organization’s designation, demonstrating their commitment to using local, organic products.

Westman describes a two-pronged approach to creating awareness of organic agriculture. Farming 101, a program of monthly workshops at the Petaluma Seed Bank, addresses topics such as small-business practices, tractor repair and irrigation, and includes onsite follow-up so participants can apply the lessons hands-on. The second approach, school field trips, gives children from other parts of the county a taste of rural Marin. In 2014, more than 2,000 students visited farms, giving kids a chance to meet the farmers and find out where their food comes from. “Children are future consumers,” says Westman, and the intent is to instill in them a value for local, sustainable agriculture.

Kids count

Field trips are a learning experience in a county where residents place a high value on education, as one might expect in an area where 92 percent have high school diplomas, and 54.6 percent hold bachelor’s or advanced degrees. The county’s k-12 public schools have scores that are among the highest in the state on the annual Academic Performance Index, with Reed School in Tiburon topping the charts with a score of 960 out of 1,000 and Novato Charter School and Old Mill School in Mill Valley following closely with scores of 945.

Marin County Superintendent Mary Jane Burke believes the outstanding performance Marin schools consistently achieve is a result of a supportive community with an understanding that investing in students is a way to keep the economy strong. “You can’t have great schools without unprecedented community support,” she says. “We have a community that holds very high expectations for public schools. What we did yesterday might be good, but it’s not good enough for today.” She points out that schools get substantial backing from businesses willing to provide financial support and members of the community, who’ve approved parcel taxes and school bonds over the years. In addition, each school has parents working together to raise funds to pay for the extras that create a quality curriculum, as well as parent-teacher associations and school volunteers, who add vibrancy.

Marin County Superintendent Mary Jane Burke believes the outstanding performance Marin schools consistently achieve is a result of a supportive community with an understanding that investing in students is a way to keep the economy strong. “You can’t have great schools without unprecedented community support,” she says. “We have a community that holds very high expectations for public schools. What we did yesterday might be good, but it’s not good enough for today.” She points out that schools get substantial backing from businesses willing to provide financial support and members of the community, who’ve approved parcel taxes and school bonds over the years. In addition, each school has parents working together to raise funds to pay for the extras that create a quality curriculum, as well as parent-teacher associations and school volunteers, who add vibrancy.“What’s unique about our schools is that we provide a well-rounded education,” says Burke, explaining that arts, nutrition and physical activity are part of the structure, and all schools pay attention to social and emotional development as well as academics. Parent-run school foundations make much of that possible and are on a constant quest to raise the money necessary to pay for the missing pieces school districts can’t afford, such as art, music, technology, library support and credentialed physical education teachers. Kiddo! in Mill Valley is one of the most successful, raising $3 million per year through a variety of programs, including a family-giving campaign and business partnerships.

Not all school foundations can raise such a large amount, however, so the individual school foundations banded together three years ago to create SchoolsRule Marin, a collaborative effort designed to benefit every child in every public school in the county, thus launching an innovative model that was the first of its kind in the United States. Burke explains that the inspiration for the Schools Rule effort came when the Marin Independent Journal offered MCOE free advertising space on a regular basis if it could find a way to benefit every public school student, regardless of economic differences. She approached the Marin Alliance for Public Schools (MAPS), a group composed of all Marin’s school foundations, which provided opportunities for networking and a way for them to share information and ideas. They didn’t hesitate, and SchoolsRule Marin was on its way.

Paul Venables, a Marin parent who’s the founder and executive creative director of Venables, Bell & Partners, donated pro-bono advertising and created the organization’s distinctive identity. In its first year, SchoolsRule Marin collected $29,000, which it divided equally per student. The concept caught on quickly with businesses, and “We now have businesses coming to us,” says Burke. SchoolsRule’s newest partner is Redwood Credit Union, which recently announced it would donate a percentage of every debit card transaction to the nonprofit, with no limit.

In October, SchoolsRule Marin distributed checks totaling $440,000 to all the public school foundations in the county, including Dedication to Special Education, an all-volunteer parent organization that serves children with special needs. It was a festive event, with members of the Miller Creek Middle School Jazz Combo Band wearing SchoolsRule T-shirts and playing trombones and trumpets that the school had purchased with the previous year’s funding. Business supporters were on hand to gain recognition, but also to celebrate the results of their largesse.

SchoolsRule Marin is just getting started. “Our goal is $1 million in 2016,” says co-chair Christina Bosch, who explains that the group did short-term and long-term strategic plans to define and reach its goals. “We’re going to accept collective responsibility for every child’s education in Marin County.”

Even with successful fund-raising, however, Marin’s schools have challenges. Almost every school district is struggling with overcrowding as more families move to the county, driving up the number of children attending public schools. “One of the effects of having great schools is that people want their kids to attend them,” says Burke. Adding to the issue is limited revenues in community-funded districts, which depend on local property taxes rather than state funding. It’s the downside of affluent communities, because while expenses increase as enrollment grows, income is fixed, thus reducing the amount school districts can spend per child. Compounding the problem are reductions in state funding and property taxes that didn’t increase as projected during the recession. “It may be 15 years before we’re back to where we were in 2007-2008,” says Burke.

Development dilemma

Dr. Robert Eyler, CEO of the Marin Economic Forum, describes Marin’s schools as a natural magnet for people across the bridges, and those from other areas who want to live in the Bay Area, so he believes the population will continue to increase, creating the demand for more housing. With little land left for development, going vertical is a solution, but Marin residents tend to be vocal opponents of high-density development. Consequently, “We’re going to have to think creatively,” says Eyler. “The demand is never going away.”

Opposition to multifamily development is increasing largely as a result of the Tam Ridge Residences, a six-building, three story complex in Corte Madera, which shocked citizens with its bulk and size and mobilized resistance to any further proposals for construction deemed not in keeping with the county’s character. “It may have taken density to the limit of what Corte Madera and Marin County will tolerate,” says Eyler. He finds that developers are reticent when they face opposition, which has an economic impact, slowing down construction as well as related jobs and employment.

Eyler points out that the vacancy rate for rentals is just 1 percent in Marin County, so the lack of new housing means betting on the local population to support the economy. He believes multifamily housing would likely draw younger, professional people and create a better demographic mix. “If you build it, I think they’ll come,” he says, although he adds that it’s important to find the right target market.

“The conversation around density is a charged one,” says Rick Wells, CEO of the Marin Builders Association. He believes, however, that it’s an opportunity for his organization to step in with a balanced approach to find creative solutions for Marin’s residents and the county’s economy. He points to Habitat for Humanity’s Mt. Burdell complex in Novato as an example of multifamily housing that satisfies almost everyone. The 10-home, affordable housing development near downtown got support from residents and approval from Novato City Council with minimal opposition. The density is acceptable to most, and it’s transit-oriented; Wells believes Marin should look more closely at that type of infill development. He adds that the purpose of the public process is to work out issues, and he sees this as an opportunity for Marin to prioritize the need for a professional and respectful discourse around the topic.

“The conversation around density is a charged one,” says Rick Wells, CEO of the Marin Builders Association. He believes, however, that it’s an opportunity for his organization to step in with a balanced approach to find creative solutions for Marin’s residents and the county’s economy. He points to Habitat for Humanity’s Mt. Burdell complex in Novato as an example of multifamily housing that satisfies almost everyone. The 10-home, affordable housing development near downtown got support from residents and approval from Novato City Council with minimal opposition. The density is acceptable to most, and it’s transit-oriented; Wells believes Marin should look more closely at that type of infill development. He adds that the purpose of the public process is to work out issues, and he sees this as an opportunity for Marin to prioritize the need for a professional and respectful discourse around the topic.In October, however, in response to protests, Corte Madera enacted a moratorium on building on Tamal Vista Boulevard, where the Tam Ridge Residences are under construction and another developer proposes replacing an aging cinema on the next block with housing. “We have yet to see how long it’s going to last—and if other communities adopt similar ‘cool-down’ strategies,” says Wells, who considers the moratorium a test and adds, “We’ll monitor to see how it develops as time goes on.”

Eyler suspects Corte Madera’s action could start a trend. “My take is that it may lead other cities to establishing moratoria on building multifamily housing,” he says. People are still going to want to live in Marin, either for access to good schools or to live closer to work, but occupancy is unpredictable. In the case of Tam Ridge, he says, “It will be interesting to see how quickly it rents and to whom.” He says it will have a residual economic impact, but without knowing who will rent the apartments—it could be aging professionals or young families—it’s impossible to know what it will be. “We’re going to continue to have traffic and housing debates,” says Eyler. But, he adds, “We need a collective voice instead of polarization.”

New frontiers

Meanwhile, says Eyler, housing and income are up, and “All the metrics look good.” He predicts continued growth in the life sciences sector, which will create new jobs and draw more people to Marin. He explains that life sciences businesses are beneficial from the standpoint of economic development, because they bring scientists and create jobs for people in an array of support services and administrative positions. They also provide opportunities for young people who are pursuing scientific careers, particularly those who grew up in Marin and want to return. “We have to support life sciences,” he says. “It gives us the best competitive advantage.”

BioMarin Pharmaceuticals, Inc., a Novato-based developer of treatments for ultrarare diseases, and the Buck Institute for Research on Aging in Novato are well established, and businesses with similar interests tend to cluster, so Marin has the potential for growth. “It’s a good play for Marin County’s economy,” says Eyler, who also observes that members of the biotech workforce are more mature, so they’re at a point in their careers where they’re often more able to live in Marin. “After age 35, the game changes,” he says, pointing out that BioMarin is located north of the Golden Gate because the company’s leaders don’t want to commute.

He gives XCell Science, Inc., a neural product and service company that was incorporated in 2010 and leases laboratory space at Buck, as a classic example of a new business. “XCell is one of the businesses that spun out of the Buck Institute,” he says, explaining that life sciences businesses are usually near academic institutions.

Andrzej Swistowski, associate director of operations overseeing XCell’s production, did his postdoctoral training at the Buck institute with XCell founder and Chief Scientific Officer Dr. Xianmin Zeng. “It’s pretty cutting edge,” says Swistowski, who described XCell’s work in his keynote speech at Marinnovation 2014, an event focusing on entrepreneurs, designers and inventors.

One of the company’s long-term goals is to generate revenue to support research into treating neurodegenerative disorders with cell-based products. One promising cell source is pluripotent stem cells, which can be reprogrammed from adult cells (such as skin or blood cells) and differentiated into any cell type in the body, thus avoiding the controversy of embryonic stem cells. “You can literally do genome editing on any genes,” says Swistowski, explaining that the procedure involves gene correction at the molecular level, which can replace diseased genes. “We obtain nondilutive financing like federal grants and contracts, and license our IP and materials,” he says, “along with selling products and providing services.”

Getting down to business

Although much of the excitement revolves around big businesses that make headlines, 93.7 percent of Marin’s businesses have 25 employees or fewer—and they’re a resource for filling all kinds of niches. “Small business is huge in having a vibrant economy,” says Eyler, who stresses the importance of creating an environment in which people have opportunities and a chance for success.

The Renaissance Center for Entrepreneurship and the Small Business Development Center on Third Street in San Rafael offer an array of classes and support services for individuals planning to launch small business, and a revitalized Venture Greenhouse, also located at the Renaissance Center, has resources to help as well. Executive Director Paul Bozzo, who spoke at Marinnovation, points out that 50 percent of small businesses fail within the first four years, and it’s the goal of Venture Greenhouse to reduce that failure rate. “It’s an incredible challenge,” he says, but “everything we need to be a successful entrepreneur is right here in the North Bay.” Among the services Venture Greenhouse offers is a 12-month intensive program to help future business owners develop the skills they need to be successful. “Entrepreneurs solve the world’s programs,” says Bozzo, and it’s important to offer opportunities when the time is right.

Once a business is up and running, the local Chamber of Commerce is one of its best resources. The San Rafael Chamber of Commerce advocates for business and meets monthly with the economic development department, the city manager and mayor to discuss issues that concern its members. In 2014, a cadre of volunteers interviewed more than 100 businesses and identified issues that can impact business’ ability to grow in San Rafael, including transportation, traffic and congestion, lack of workforce housing and regulations. The chamber presented a study summarizing the issues to the city, and “It was really well received,” says Chamber President/CEO Joanne Webster.

“We have a sense the business climate is improving,” she adds, and cites as indicators BioMarin’s acquisition of property in downtown San Rafael, the desire of EO Products to expand and Marin Academy’s plan to add a science wing. In addition, the chamber is working to attract more life sciences businesses. “We’re working with that sector to see what their needs are,” says Webster, observing that those types of companies require access to high speed Internet and enjoy the proximity to amenities. “I thinking banking and financial is going to grow,” she adds, and she sees businesses moving north to Marin from San Francisco because “It’s a little less expensive,” she says.

Education is also a priority, says Webster, who reports that, among the chamber’s initiatives, it connected Redwood Credit Union with San Rafael High School to facilitate a financial literacy program for the students, called Bite of Reality. “It’s amazing how little these kids know about finances,” says Webster.

Marin’s Hispanic Chamber of Commerce is also active in the community as a resource for Latino businesses, a diverse mix ranging from restaurants to dog groomers to larger businesses such as Mi Pueblo Food Center, a supermarket in East San Rafael that offers Hispanic products such as nopales (cactus leaves). Among the new trends, “We’re seeing an increase in home-based business, such as strategic planners, accountants and lawyers,” says Cecilia Zamorra, president of the Hispanic Chamber of Commerce and executive director of the Latino Council. She also sees the younger generation—often children of immigrants—going to college and returning to the community in positions where they can help others, often in social work or law. She points to Mark Talamantes, Marin County’s first Hispanic judge; public defender José Varela; and Dr. Graciela Carranza, a chemist at Dominican University who mentors Latino students, as examples.

A healthy outlook

To thrive, a county needs healthy residents, and Marin has three major hospitals to serve their needs: Kaiser Permanente San Rafael Medical Center, Sutter Health’s Novato Community Hospital and Marin General Hospital in Greenbrae.

Marin General Hospital (MGH) returned to local control in 2010 after the Marin Healthcare District, a public entity, broke its lease with Sutter Health. In 2013, voters approved a $394 million general obligation bond to cover the cost of rebuilding the aging hospital to make it earthquake-safe, as required by the state. “We’re in design development,” reports Marin Healthcare District and MGH CEO Lee Domanico, and the next step is construction documents. The first stage of construction is a parking garage, slated for early 2015, and the hospital replacement project work will start later in the year. The site is challenging because it’s smaller than desirable for a hospital of MGH’s size, but, says Domanico, “We’ve come up with an outstanding solution,” part of which is building the parking garage to cut into the hill next to the campus. The new hospital will be four stories, close to the height it is now, to make it compatible with the neighborhood.

Marin General Hospital (MGH) returned to local control in 2010 after the Marin Healthcare District, a public entity, broke its lease with Sutter Health. In 2013, voters approved a $394 million general obligation bond to cover the cost of rebuilding the aging hospital to make it earthquake-safe, as required by the state. “We’re in design development,” reports Marin Healthcare District and MGH CEO Lee Domanico, and the next step is construction documents. The first stage of construction is a parking garage, slated for early 2015, and the hospital replacement project work will start later in the year. The site is challenging because it’s smaller than desirable for a hospital of MGH’s size, but, says Domanico, “We’ve come up with an outstanding solution,” part of which is building the parking garage to cut into the hill next to the campus. The new hospital will be four stories, close to the height it is now, to make it compatible with the neighborhood.

Domanico describes the new hospital as a state-of-the-art facility combined with a healing environment, which is in keeping with the culture of Marin. It incorporates green building standards, and the interior separates the in-patient flow from the public, providing more privacy and infection control, while the design includes lots of natural light with gardens everywhere. “We hope every patient will have a view of nature,” says Domanico.

Striving to provide the best care for its patients, “We have the latest robotic technology; it’s quite phenomenal,” says Domanico, who explains that robotic surgery is better for the patient, because there’s less blood loss, it leaves smaller scars, is less painful and the recovery time is shorter. Some procedures can even be done through a single incision—like gallbladder removal. The Center for Integrative Health and Wellness takes a holistic approach that focuses on the whole person by weaving integrative therapies into the patient’s overall healing plan, such as massage, jin shin jyutsu, nutritional counseling and guided imagery. “The hospital is an intersection of highly complex technology and healing, and the integrated program is part of that,” says Domanico. Safety is also a priority, and a unique initiative aims to make MGH one of the safest hospitals in the country. “We’re putting all our employees through safety training,” Domanico reports.

The implementation of the Affordable Care Act has brought some changes, but mostly to the bottom line. “Our bad debts have gone down somewhat,” says Domanico, but he doesn’t see any notable increase in the number of patients seeking treatment as a result of the ACA. “Our emergency department visits have increased year after year,” he says, while the number of inpatients has decreased, probably because the hospital has more observation patients, who fall between inpatient and outpatient care, receiving treatment for one day and then going home.

With new concepts in health care and plans for a new hospital underway, MGH is moving forward, and even though it’s just four years into local control, its efforts appear to be paying off. Among its honors, in 2014 MGH was ranked as one of the top 100 hospitals in the country for coronary care and coronary intervention, and it received a Distinguished Hospital Award, putting it in the top 5 percent nationally for outcomes.

Wide open spaces

Fresh air and nature are an integral part of a healthful lifestyle for Marin residents. Open space accounts for 18,500 acres, and an abundance of parks provide recreational opportunities galore, from disc golfing at Stafford Lake Park in Novato to fishing and picnics at Paradise Beach Park in Tiburon. Even dogs have their own parks. At Mill Valley’s Bayfront Park, dogs can play with canine pals and chase tennis balls, and they also have a place to swim and a spectacular view of Mt. Tamalpais.

People put a high value on open space and are always fearful of losing it, but in April 2014, the opposite happened in Novato, when a backhoe scooped up a load of mud and breached a levee on the former airfield at Hamilton Air Force Base, letting water from San Pablo Bay flow into the wetlands for the first time in a century. Former runways and traces of the farms that had been there before them disappeared into history, wildlife discovered a new habitat, and outdoor lovers found new recreational activities on a path along the perimeter of the wetlands that adds 2.7 miles to the San Francisco Bay Trail.

Tom Gandesbery of the State Coastal Conservancy reports seeing avocets, black-necked stilts, white pelicans and winter-migrating duck and geese, along with mammals like raccoons, deer, coyotes, river otters and harbor seals in the area. “These animals came onto the site the day we allowed water to flow back,” he says. He expects the wetlands, which occupies about one square mile, to change rapidly over the next decade, and a comprehensive monitoring plan will track the progress.

The Hamilton Wetlands Restoration Project was a collaborative effort involving the city of Novato, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the Coastal Conservancy and a huge cadre of volunteers. Christina McWhorter is responsible for the project’s nursery and the growing and planting of thousands of native plants, with species such as Coast Live Oak, Gumplant and Pickleweed among them. “All of the plants we grow and plant are local, native plants, representing local genetic diversity,” she says. Hundreds of volunteers, including individuals, students from local schools and community groups, helped plant the site in 2014 and continue to collect seed, grow native plants and monitor the survivability of the vegetation as the project progresses. Currently, a team of 12 AmeriCorps members is helping establish 11,700 plants in the site’s north seasonal wetlands.

Something for everyone

Something for everyone

Marin County is fertile ground for eclectic tastes, and it’s rich in the arts, with a wealth of galleries, theaters and music venues, including the county-owned Marin Center, which has its own cultural programs. The complex includes the 2,000-seat Veterans Memorial Auditorium, the 22,500-square-foot Exhibit Hall, the 315-seat Showcase Theater and the fairgrounds, with a 14-acre lagoon, walking paths, lawns and gardens. “I really see this entire campus as the cultural center for the county of Marin,” says Gabriella Calicchio, director of cultural and visitor services.

The Marin Center’s programming at the auditorium runs the gamut, from Mummenschanz, a Swiss company that does magic onstage using recycled materials, to Hal Holbrook’s one-man show Mark Twain Tonight. Calicchio, who stepped into the director’s position after longtime director Jim Farley retired in 2014, explains that the focus is on world culture. “Our programming is global, with international classic and contemporary artists,” she says. The auditorium is also the venue for a popular speakers’ series, and it’s available for rent to other organizations, such as local dance schools and the Marin Symphony, which began performing at the Veterans’ Memorial Auditorium when it opened in 1971. “They consider us their home,” says Calicchio.

The Exhibit Hall is also for rent. “It’s used for all sorts of events, from the Gem Faire to fund-raising galas to the annual Bioneers Summit Conference. The space can be transformed into almost anything,” says Calicchio.

The center’s biggest, most spectacular annual event is the Marin County Fair, which takes over the entire campus for five days at the beginning of summer and features exhibits, performances, a barnyard, a carnival with rides and games and fireworks every night of its run. “The fair is amazing. It’s one of the most innovative, creative and exciting fairs in the country,” says Calicchio. She particularly likes the competitive exhibits and finds the fine art exhibit in the Redwood Foyer of the Veterans Memorial Auditorium special. “Family fun at the fair means families can work together on competitive exhibits, such as the Art Chairs and Art on the Spot, in addition to our traditional fair offerings.

The center’s biggest, most spectacular annual event is the Marin County Fair, which takes over the entire campus for five days at the beginning of summer and features exhibits, performances, a barnyard, a carnival with rides and games and fireworks every night of its run. “The fair is amazing. It’s one of the most innovative, creative and exciting fairs in the country,” says Calicchio. She particularly likes the competitive exhibits and finds the fine art exhibit in the Redwood Foyer of the Veterans Memorial Auditorium special. “Family fun at the fair means families can work together on competitive exhibits, such as the Art Chairs and Art on the Spot, in addition to our traditional fair offerings.“I’m thrilled to be here,” says Calicchio, a Marin resident who was with Marin Theatre Company and the Walt Disney Family Museum before taking on her new position at the Marin Center. She sees it as an enormous opportunity and would like to collaborate with businesses and members of the community to make it an even more robust place.

On the tourist trail

Many of the things that make Marin County a desirable place to live are also attractive to tourists. Mark Essman, president/CEO of the Marin County Convention and Visitors Bureau, observes that Marin is small, laid back and has lots of outdoor activities—and that’s why people visit. Increasingly, visitors are using technology to find the places they want to experience, and to meet the need, the bureau offers an interactive iMap software program, which people can use on their portable devices or computersto get a taste of Marin and plan their itineraries.

Marin’s most popular spots are Muir Woods, Point Reyes National Seashore, the Golden Gate National Recreation Area and Mount Tamalpais. The diversity of Marin’s communities is also a plus. “Each area is a totally different world,” says Essman. Marin’s reputation for food and the farm-to-table movement continues to grow, and the Sonoma Marin Cheese Trail is a hit with its colorful map for self-tours. “We go through those things like crazy,” says Essman.

Sporting events are also big. The Dipsea, an annual foot race over Mt. Tamalpais from Mill Valley to Stinson Beach draws people from all over, and the San Rafael Pacifics offer baseball fans a chance to see games live. “They’re fantastic games if you want to see great professional ball,” says Essman.

Signature events, such as the Mill Valley Film Festival and the Sausalito Arts Festival, also put Marin on the map. “They give us an identity. Marin can wear many hats,” says Essman, who observes that [events like these] result in revenue for restaurants, hotels and retail stores. He reports that the average day-tripper spends $100 to $150 in the county.

In the spotlight

One of the year’s biggest events is the Mill Valley Film Festival, which draws people from all over the world for an extravaganza of film, parties, music, awards and the chance to spot celebrities and experience the buzz of a major film festival first-hand. MVFF37, in October 2014, broke records with attendance tallying 61,000, and cinemophiles even had a chance to discuss their favorite films while on an organized group hike to Tennessee Valley Beach.

Demonstrating strong community partnerships, MVFF has a long list of sponsors, supporters and volunteers. In 2014, for the first time, it embarked on a partnership with the Latino Council and the Marin Hispanic Chamber of Commerce to produce ¡Vive el cine! and showcase the best films from Spanish and Portuguese-speaking filmmakers. The goal was to add a new element to enrich audiences. “We’re interested in the success of a multicultural community,” says Cecilia Zamorra, who hopes the program will continue next year.

It’s a community partnership that’s typical of Marin County, with its zeal for innovation and enthusiasm for new ideas. Thinking big is part of the environment, and when people collaborate to make life better, they are the county’s best asset.

Rallying for a Cause

Shifting Gears made its debut with a car rally, gala and auction in 2013 and raised $400,000 for the rare genetic disease Myotonic Dystrophy. On the road again in October 2014, it netted $167,000 for San Rafael-based Roots of Peace. The three-day drive through the countryside of Marin, Sonoma and Napa counties began with breakfast at Hilltop 1892 in Novato on Thursday, October 9, where a representative of the U.S. State Department was on hand to announce that the agency would match whatever Shifting Gears raised, so the final tally was $334,000.

Marin resident Heidi Kuhn founded Roots of Peace in 1997 to remove land mines from farmland in war-torn countries and return the land to productive use. “We try to find organizations that are somewhat smaller and need help,” says Shifting Gears founder Charles Goodman, who explained that, in addition to raising money, one of the goals was to increase awareness of Roots of Peace and its mission. The funds will pay for the removal of land mines in Vietnam, which is especially meaningful to the classic-car aficionados who participated in the rally, because many of them are from the Vietnam War era.

Marin resident Heidi Kuhn founded Roots of Peace in 1997 to remove land mines from farmland in war-torn countries and return the land to productive use. “We try to find organizations that are somewhat smaller and need help,” says Shifting Gears founder Charles Goodman, who explained that, in addition to raising money, one of the goals was to increase awareness of Roots of Peace and its mission. The funds will pay for the removal of land mines in Vietnam, which is especially meaningful to the classic-car aficionados who participated in the rally, because many of them are from the Vietnam War era.2015’s event is already in the planning stages and will benefit Beyond Differences, a Mill Valley-based organization dedicated to addressing social isolation in middle school and creating an inclusive culture.

Pictured: Tom O’Neill, a member of the board of directors of Marin philanthropy Shifting Gears, with his classic 1956 Austin Healey 100 at the Pacific Coast Air Museum at the Charles M. Schulz–Sonoma County Airport in Santa Rosa. O’Neill’s car appeared with a similar aircraft in a magazine ad to promote the model in 1955. [Photo by Peter Herley]

Marin County Office of Education

“When it’s good to be big, we’re big, and when it’s good to be small, we’re small,” says Marin County Superintendent of Schools Mary Jane Burke, listing the array of services MCOE provides, which include:

• Special Education programs for individuals from infancy to 22 years

• School-to-Career Partnership, with more than 200 businesses providing internships for high school students

• County Community School, an alternate school for high school students who’ve been expelled or have problems with the law, drugs or alcohol

• Education program at Marin County Juvenile Hall

• Regional Occupational Program so students can engage in hands-on learning, letting them learn skills such as those offered in a small-engine class at Tamalpais High School in Mill Valley

• Collaboration with Homeward Bound on its Fresh Starts Culinary Academy to prepare students for jobs in the food industry

• Walker Creek Ranch Outdoor School to give 7,000 students per year the chance to spend a school week experiencing nature and observing a working ranch up close

• Programs in technology in partnership with the Workforce Investment Board

• School-Law Enforcement Partnership

• Professional development for all school staff, including classified employees as well as teachers

• Oversight of district budgets

• Payroll services for every district (except Novato Unified School District)

• Monitoring of credentials

• Acting as an intermediary between the state and local school districts

The numbers

Student enrollment 2013 to 2014: 32,192

Number of school districts: 19

Largest school district: Novato Unified School District, 8,000 students

Smallest school district: Union Joint School District in rural Marin, 11 students

Trends in the Hotel-Motel Business

Mark Essman of the Marin Convention and Visitors Bureau says tourism is up, and lots of people are walking into the Bear Valley Visitors Center in Olema. “This has been a very, very strong year,” he says, with good weather, no fires, no catastrophic events and an economy that’s improving. Most of Marin’s visitors are day-trippers, but people come for a variety or reasons, so hotel occupancy is also up and was 93.4 percent in August.

Market mix for Northern California (not including San Francisco)

Leisure 36.5 percent

Commercial 28 percent

Group 27.8 percent

Other 7.8 percent

Source: NoCA Trends in the Hotel Industry, July 2014

College of Marin

The College of Marin offers a two-year program leading to an associate degree and the opportunity for students who complete the requirements to transfer to a school in the University of California system. The college has two campuses, Kentfield (77 acres) and Indian Valley (333 acres), and both are in the midst of facilities modernization, upgrading existing buildings and building new ones with funds generated from a $249.5 million bond that voters passed with a 60 percent majority in 2004, demonstrating their support for upper education.

Marin residents have a passion for learning, which is reflected in COM’s diverse student population. In spring 2014, COM offered 935 classes; the youngest student was 11, while the oldest was 80. The average age of credit students is 34 years.

In addition to the credit program, COM’s Community Education program offers a variety of classes, including computers, foreign language, art, physical education and artisan cheesemaking. In spring 2014, 24 percent of participants were men, while 74 percent were women (3 percent didn’t report).

The college received an anonymous donation of $50,000 in 2014, allowing the emeritus program to provide scholarship for students over age 55 who can show financial need.

COM in Spring 2014

Credit Classes

Total students enrolled 6,305

Full time 1,489

Part time 4,816

Age 20 or younger 1,540

Students 21-24 1,095

Students 25-34 1,295

Students 35-44 718

Students 45-54 661

Students 55 and over 996

Students with bachelor’s degrees or higher 1,386

Non-credit classes

In spring 2014, 1,273 students were enrolled in noncredit classes. The majority were studying English as a second language (ESL).

Community Education

Total students enrolled 1,859

Students under 19 29

Students 20-29 79

Students 30-39 68

Students 40-49 147

Students 50-59 317

Students 60-69 630

Students 70+ 587

Source: College of Marin Student Characteristics, Spring 2014

Marin County Snapshot

Estimated population, 2013 258,365

Residents under 5 5 percent

Residents under 18 20.6 percent

Residents over 65 18.9 percent

White 86.2 percent

Hispanic 15.7 percent

Asian 6 percent

Black or African American 2.8 percent

Females 51.1 percent

Housing units 111,547

Housing units/multi-unit structures 26.9 percent

Home ownership rate (2008-2012) 62.6 percent

Number of businesses (2007)41,712

Source: United States Census Bureau