NorthBay biz celebrates its 40th anniversary with a look at how the local food and restaurant scenes have changed over the years.

“The lifetime of most restaurants isn’t long,” says author, teacher and chef, John Ash. “Things are changing so quickly that either the owner goes on to something else or the concept gets tired. The demand to remain on the cutting edge is more important now than it’s ever been.” Still, some restaurants have been going strong, under the same ownership, for many years. We talked to a few owners who know all about longevity in this volatile business.

“The lifetime of most restaurants isn’t long,” says author, teacher and chef, John Ash. “Things are changing so quickly that either the owner goes on to something else or the concept gets tired. The demand to remain on the cutting edge is more important now than it’s ever been.” Still, some restaurants have been going strong, under the same ownership, for many years. We talked to a few owners who know all about longevity in this volatile business.Eat at Joe’s

Marin Joe’s is your quintessential neighborhood Italian restaurant. Adolph Della Santina opened it in 1954 after he sold Original Joe’s, the restaurant he started in San Francisco when he first came over from Lucca, in Tuscany. (In 1948, his nephew, Romano Della Santina, had immigrated and joined the Adolph’s San Francisco business; he came with his uncle north to Marin.) The marketing plan Great Uncle Adolph laid out, and which is still followed today, is simple, says chef Paul Della Santina, who now owns the restaurant with his father, Romano, and his brother, Ralph: “Put good food on the table.”

The food at Joe’s is classic. “Good, comfortable food that works,” says Paul. “No gimmicks.” He has a mesquite broiler and is famous for his steaks, chops and especially burgers. “I always do a lot of fairly traditional Italian dishes, too. Our menu is pretty much all over the board. You can come in and have a bowl of soup, a nice piece of French bread, some Parmesan cheese and a glass of wine and call it a meal; or you can have a Caesar salad, split a pasta and have a double porterhouse—and everything in between.”

The food at Joe’s is classic. “Good, comfortable food that works,” says Paul. “No gimmicks.” He has a mesquite broiler and is famous for his steaks, chops and especially burgers. “I always do a lot of fairly traditional Italian dishes, too. Our menu is pretty much all over the board. You can come in and have a bowl of soup, a nice piece of French bread, some Parmesan cheese and a glass of wine and call it a meal; or you can have a Caesar salad, split a pasta and have a double porterhouse—and everything in between.”With a few exceptions, the menu has remained pretty much the same over the years, “We haven’t lived by any trends, so we’re not going to die by a trend, either.” Nevertheless, he does acknowledge that, in recent years, people have begun to ask for different things.

He’s aware of the trend toward organic produce and antibiotic-free beef, for example, but he maintains the price standard his customers are comfortable with. “I’m not in the upper tier of prices. I’ve bought my hamburger from the same company forever,” he says. “People love it and they’re comfortable with the price.

“I try to stay true to me,” he adds. “It’s not to say I don’t watch trends. Over the last 15 years, I’ve added more chicken because people are eating more chicken. But steaks never went out of style at Joe’s. Just like hamburger never went out of style at Joe’s.” Bottom line? “I think the main thing is it’s still fun!”

For Joe’s, it’s about giving people what they want—what will make them feel good, feel special. The oddball vegetarian in the steakhouse need not feel bad, laughs Paul. “If you’re a vegetarian, I can fix you up one heck of a meatless pasta dish,” he says. “If you’re gluten free, I can fix you up one heck of a vegetable plate, because I have numerous fresh vegetables every day. If you have a peanut thing, just tell me, and I’ll use olive oil.” He laughs. “We wouldn’t have been here 60 years if we couldn’t accommodate!

“Back when Ralph and I were kids, there were just a few restaurants up the freeway,” he remembers. “We’d see our friends here. We’d go away to school and then come home for the holiday, and our parents would bring us in here and we’d see each other again. Now I have buddies who moved away and are coming back for family reasons. I see it come full circle.”

The restaurant’s core values have stayed the same, but Paul isn’t oblivious to changes in the culture. “Work ethics have changed over the years. People now are more willing to move to another job for a few more bucks, where people years ago liked the stability of staying in one place for a long time. But I have a steady workforce that’s gotten to know customers and customers know them, and it gives everyone a homey feeling.”

Organic produce in West Marin

Organic produce in West Marin

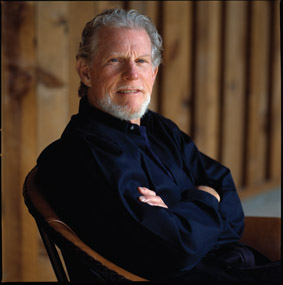

Back in 1974, when the job market for English Ph.Ds was close to nonexistent, Warren Weber migrated from Berkeley to Bolinas to do what a lot of creative people at the time were doing: trying to make an alternative living in a beautiful area. He knew something about farming, saw organic as the way to go and founded Star Route Farms. “We did it organically because that seemed the right thing to do,” he says, “and it took off!” Weber started with five acres. He now has 100 acres in Bolinas and another 80 in Coachella Valley.

Weber originally sold his produce to the few local natural food stores, such as Good Earth in San Rafael and Our Store in San Anselmo, and to distributors who sold produce all over the country. The farm-to-table culture had not awakened yet in Marin when, in the early 1980s, he got a call from Sibella Kraus at Chez Panisse, Berkeley’s mecca for local, organic cuisine, and he started selling to it and other Bay Area restaurants.

A decade later, his marketing model changed. Suddenly, the really big shipper-growers (those growing 5,000 plus acres) got into the organic industry, knocking out the smaller growers like Weber, who were selling to distributors. In response, he says, “We shrunk our operation in the desert and decided to rely only on the restaurants.” It was an adjustment. Whereas distributors would take what you have in-season, restaurants wanted the same thing year-round. “Basically, we just wanted to sell to people who wanted what we had and who understood the value of organics.”

In 1999, farmers’ markets boomed and Krause called again, this time with news she was running the farmers market at the San Francisco Ferry Building. Weber now sells to that market and also the Marin Farmers Markets on Thursday and Sunday at the Civic Center in San Rafael; the rest of his produce goes directly to restaurants.

“We’re really doing it for the customer,” he says. “We want to have good customer relations and give people what they want.” He thinks for a moment. “It’s kind of ironic that we’re still here. Restaurants come and go—that’s a tough business, but so is farming.”

Establishing a classic

Establishing a classic

In 1979, Bill Harlan was looking to create a great wine estate and found a beautiful property in St. Helena. It wasn’t the ideal vineyard property he was hoping for, but it had been an old private country club, and he and his partners thought it could be a perfect place for a signature resort. They named it Meadowood.

“This valley is about three things,” says Harlan, “wine, hospitality and food. Our goal was to create not only the wine and food, but also the level of the service people would expect—and for the three to come together to create a whole experience.”

To launch the restaurant, which has always been excellent and today, under executive chef Christopher Kostow, boasts three Michelin stars, Harlan took a chance on an emerging chef named Cindy Pawlcyn. “She was young, she was bright, had a great attitude and good relationships that gave her excellent support,” remembers Harlan.

Pawlcyn put Meadowood’s restaurant on the map before moving on to another Napa chef position. In 1983, she went on (with partners) to start Mustards Grill, which has been a mainstay of Wine Country cuisine since.

“Cindy has certainly made a contribution to our valley over the last 35 years,” says Harlan. “She’s supported the community in many different ways. She’s donated her time, helped other young people who’ve come to the valley; she genuinely cares about the people she works with as well as her patrons. I feel she’s made a great difference in our valley.”

Cuisine in the middle of nowhere

Cuisine in the middle of nowhere

In 1983, Napa Valley was a different place, says Pawlcyn. “There were only 90 wineries. There were cattle ranches, walnut orchards, prune orchards. Now it’s all vineyards,” she says. “It’s always stayed beautiful. I’m always grateful for that—and for our ag preserve, which has kept part of it in woods so it’s not completely taken over.”

For Pawlcyn, staying in business over time is a matter of pleasing her evolving customer base. “You have to keep the clients who started with you happy, and then always be doing exciting things for the new clientele,” she says. Right from the start, she’s worked her menu to pair beautifully with the great wines available in the area. “The wineries have been very generous and supportive of us,” she says. “We fit a niche in the valley very well: We cook things that go well with wines.”

How have diners’ tastes changed over the years? “I think good taste is good taste,” says Pawlcyn, “but I think people are actually becoming more adventuresome.” With accessibility to so much more media and information, younger people are open to experiencing exciting new cooking, new chefs, new concepts, “like pork belly and tongue,” she says, and new styles of cooking. For example, “You see more Asian influence than you used to.”

As for her menus, there are some things her customers simply won’t let her change, such as her Mongolian Pork Chop (see recipe below). It’s been on the menu from the start. Now lamb is big as well. “We used to do one or two lambs in a week. Now we do five, maybe even six. We use Don Watson Napa Valley lamb. And we use the whole animal and serve them many different ways.”

Country French in Glen Ellen

Country French in Glen Ellen

After working up from the deli counter to director of operationsat Viansa Winery in Sonoma County, since 1993, Sondra Bernstein decided to start her own restaurant in 1997. She found an affordable place in Glen Ellen not far from where she lived and brought John Toulze with her from Viansa as a “jack-of-all-trades; a few years later, he became chef at the restaurant. Together, they’ve made the girl & the fig (now in Sonoma) and the fig café & winebar in Glen Ellen local institutions.

Bernstein says the menu is totally to her taste. “I knew I wanted to do French. There wasn’t a lot of French at that time.” Their rustic French menu features local produce, much of it raised in the biodynamic gardens they sharecrop at Imagery Estate Winery, and local meats and cheeses. The wine list is all Rhone varietals, mostly from California, which go particularly well with the food.

In 2000, she relocated the girl & the fig restaurant to a busy corner on the Plaza in Sonoma, and reconstituted the original restaurant in Glen Ellen first as the girl & the gaucho and, later, as fig café. The café, after 17 years, has just reopened after a complete renovation.

In Sonoma, the girl & the fig serves a high percentage of visitors, especially in the summer, but in Glen Ellen, the clientele is predominately local. “A lot the same people have been coming since we were opened,” she says. “They came with their babies. Some of their kids had their first jobs with me. Now we’re doing their wedding rehearsal dinners. We’ve also built some very long-term relationships with local wineries, farmers and growers.”

During her tenure, the community has changed to reflect the times. “Now, it’s very vibrant,” she says. “We have a lot of restaurants now, and there are more tasting rooms than we’ve ever had. The area is in more disrepair—there are more homeless—but the core people who’ve been living here since I can remember still come in. They still like what they like.”

She doesn’t remember the year, but there was a time when they (Bernstein and Toulze) thought they might have to sell the business. “We were really struggling, so we added complimentary corkage to the mix. That saved our business. More people came in.” And they’re still coming.

“My philosophy is that, as long as people are coming, we have one job to do. That’s to make them happy. There’s no other reason to be in the business.”

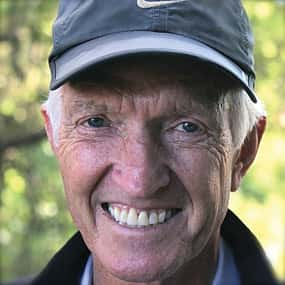

40 years of cooking

When he started in the cooking business 40 years ago, Chef John Ash found the best food in America was French-inspired cuisine. “It didn’t matter where you went in America, if you went to the best restaurant in town, it was French. Now, the French are coming to us for inspiration, and we’re looking to other cultures for inspiring, authentic tastes.”

He calls the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s, the “golden age of the discovery” of wine in America. “Now,” he says, “we’re in the next beverage revolution. Whole restaurant themes are being developed around beverages—craft beers and artisan spirits—the part of the restaurants that make the most money. At the same time, there’s been a push-back against commodity wineries and a growing interest again in small producers making great varieties that most of us don’t know much about.

“It’s a little bit of a cliché,” he says, “but still very much alive and growing is the farm-to-table movement focusing on local, seasonal ingredients. It’s fun to go to the restaurants for the young chefs who say they won’t serve anything from further than 50 or 100 miles from their restaurant. It’s a challenge [for them], but it’s fun.”

While a few great, traditional fine dining restaurants, such as Meadowood in Napa and Madrona Manor in Sonoma, will prosper thanks to their long-established clientele, a new breed of sophisticated diners (including millennials), who’ve often traveled all over the world, are seeking cuisines that are new and different. “It’s getting us all outside of our comfort zones,” Ash says, with a laugh that suggests he enjoys it.

Summing up

“It’s a chef’s heaven,” says Pawlcyn. “The North Bay has the best producers, the best growers and the best weather. There’s such a broad range of ingredients. Every year, there are more things we can grow in the garden at Mustards. Every year, there are more things people are looking for and wiling to try.”

“There’s no question, the consumer is much more savvy, smart and entitled,” agrees Bernstein. “I think people work hard for their money and, when they go out, they deserve to have a quality experience.”

“We’re so lucky to be here!” enthuses Ash. “Overall, I can’t think of a better place to be.”

Mongolian Pork Chops

By Cindy Pawlcyn

By Cindy Pawlcyn Serves 6

6 (10-ounce) center-cut double pork chops

Mongolian Marinade

1 cup hoisin sauce

1 tablespoon sugar

1 ½ tablespoons tamari soy sauce

1 ½ tablespoons sherry vinegar

1 ½ tablespoons rice vinegar

1 scallion, white and two-thirds of the green parts, minced

1 teaspoon Tabasco sauce

1 ½ teaspoons Lee Kum Kee black bean chile sauce

1 ½ teaspoons peeled and grated fresh ginger

1 ½ tablespoons minced garlic

¾ teaspoon freshly ground white pepper

¼ cup fresh cilantro leaves and stems, minced

1 tablespoon sesame oil

Chinese-Style Mustard Sauce (see below; prepare prior to cooking the pork)

Trim the excess meat and fat away from the ends of the chop bones, leaving them exposed. Put the pork chops in a clean plastic bag and lightly sprinkle with water to prevent the meat from tearing when pounded. Using the smooth side of a meat mallet, pound the meat down to an even 1-inch thickness, being careful not to hit the bones. Alternatively, have your butcher cut thinner chops and serve two per serving. To make the marinade, combine all ingredients in a bowl and mix well. Coat the pork chops liberally with the marinade and marinate for three hours (up to overnight) in the refrigerator.

Prepare the mustard sauce, coordinating the timing so it will be ready when the chops come off the grill.

Place the chops on the grill and grill for five minutes on each side, rotating them a quarter turn after two to three minutes on each side to produce nice crosshatch marks. It’s good to baste with some of the marinade as the meat cooks. As with all marinated meats, you want to go longer and slower on the grill versus shorter and hotter, because if the marinated meat is charred, it may turn bitter. The pork is ready when it registers 139 degrees on an instant-read thermometer. Serve with the mustard sauce.

Chinese-Style Mustard Sauce

Makes about 2 cups

½ cup sugar

¼ cup Colman’s mustard powder

2 egg yolks

½ cup red wine vinegar

¾ cup crème fraîche or sour cream

Put the sugar and mustard in the top of a double boiler and mix with a whisk. When well combined, whisk in the egg yolks and vinegar. Cook over simmering water, stirring occasionally, for 10 to 15 minutes, until it is thick enough to form ribbons when drizzled from the spoon. Remove from the heat and let the mixture cool. When cool, fold in the crème fraîche. Keep refrigerated until needed.

Source: Mustards Grill Napa Valley Cookbook (Ten Speed Press)

Fig & Arugula Salad

By Sondra Bernstein and John Toulze

By Sondra Bernstein and John ToulzeServes 6

Vinaigrette

3 dried Black Mission figs

1 cup ruby port

¼ cup red wine vinegar

½ tablespoon minced shallots

¼ cup blended oil

Salt and pepper to taste

Pour the port in a bowl, add the figs and rehydrate until soft. Transfer the port and figs to a saucepan. Reduce the port over medium heat to ½ cup, about five to seven minutes.

Transfer the port mixture to a food processor and add the vinegar. Purée until smooth. Add the shallots and slowly whisk in the oil. Season to taste with salt and pepper.

Salad

½ cup pancetta, diced

12 fresh figs, halved (see Food for Thought)

6 bunches baby arugula

1 cup pecans, toasted

1 cup goat cheese, crumbled (preferably Laura Chenel Chévre)

Freshly ground black pepper to taste

Sauté the pancetta in a small sauté pan over medium heat until the pancetta is crisp. Set the pancetta aside, reserving the “oil.” Brush the figs with the pancetta “oil.” Grill

the figs for 45 seconds on each side. In a stainless-steel bowl, toss the arugula, pecans, pancetta and goat cheese with the vinaigrette.

Divide the salad among six chilled plates and surround each plate with the grilled figs. Grind the pepper over each salad.

Food for Thought

If fresh figs aren’t in season, substitute good-quality, moist dried figs (Orchard’s Choice figs are a favorite). We don’t recommend grilling dried figs; just cut them into small pieces and toss with the other salad ingredients.

This is the original Fig & Arugula Salad from 1997 that we still serve today!

Miso Marinated Black Cod

By Chef John Ash

Serves 6

Black cod (also known as sablefish or butterfish) is a sustainably caught fish. much of which comes to us from the Pacific Coast from Northern California up to Alaska. Miso is the traditional Japanese fermented paste made commonly with soybeans but also with rice and/or barley. Its best-known use in America is as the base for Miso soup. It also makes a wonderful marinade and the following can be used on all kinds of fish, chicken or pork. If you can’t find black cod, use salmon or halibut.

3 tablespoons mirin*

3 tablespoons sake wine*

1/2 cup white shiro miso*

1/3 cup sugar

6 skinless, 6-ounce cod fillets cut 1-inch thick

3 tablespoons canola or other vegetable oil with a high smoke point

Garnishes: seaweed salad or sweet pickled sushi ginger, daikon sprouts and toasted sesame seeds, if desired

Add mirin, sake and sugar to a small saucepan and bring to a simmer. Stir until sugar is melted. Whisk in miso until smooth. Transfer to a bowl and cool. Add fillets, turn to coat well, cover with plastic and refrigerate for at least six hours or overnight.

Preheat oven to 400 degrees. Add oil to an oven-proof sauté pan large enough to hold the fish in one layer. Heat the oil over moderately high heat. Scrape the excess marinade off the fish and cook until lightly browned on one side, about two minutes. Turn fish and place in oven until cooked through and flaky, about six minutes. Serve on warm plates topped with garnishes.

*available in Asian markets and some supermarkets.