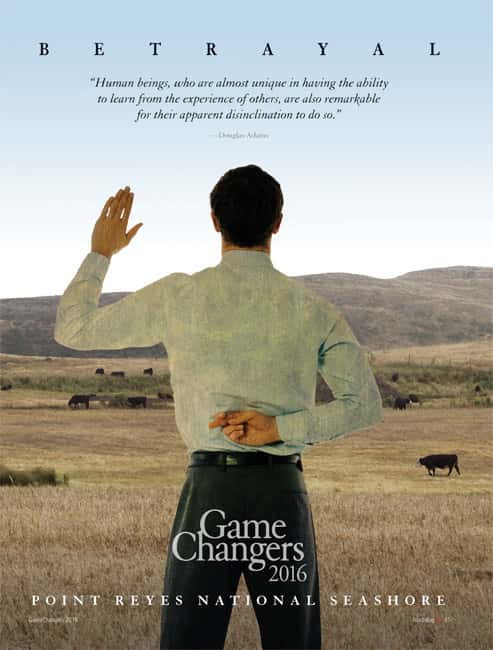

“Human beings, who are almost unique in having the ability to learn from the experience of others, are also remarkable for their apparent disinclination to do so.” —Douglas Adams

The other shoe dropped February 10.

The other shoe dropped February 10.

If you ask the ranchers and dairy farmers who make their living inside the bucolic confines of Point Reyes National Seashore, they’d tell you the shoe was a Ferragamo wingtip owned by one of the lawyers who filed the lawsuit against the National Park Service (NPS) essentially questioning whether ranching should continue in the park.

On the other hand, if you asked Huey Johnson over at Mill Valley’s Resource Renewal Institute, one of the folks who brought the lawsuit, he’d tell you it was more like a hiking boot.

No matter what style kicks they might be, ranchers and farmers have been waiting for this lawsuit—or something like it—ever since Kevin Lunny and the Drake’s Bay Oyster Company were given the boot. That action, years in the making, made it official that neither the NPS nor the courts were going to let Drake’s Bay continue operations after its 2012 agreement expired.

That fight made the dairy farmers and ranchers nervous, worried that their days in the National Seashore were numbered. So then-Interior Secretary Ken Salazar ordered his staff to fashion 20-year lease extensions for the ranches in the park—but those leases didn’t happen. By 2014, tensions between the ranchers and the NPS had grown to the point where the Park Service began what it called a “truth and reconciliation” campaign in an attempt to mend fences with the ranchers and make the lease extensions a reality.

This year, a couple days before Cupid’s traditional visit, Johnson, the Center for Biological Diversity and the Western Watersheds Project sent their own type of valentine to the National Park Service and Marin native Cicely Muldoon, superintendent for the Point Reyes National Seashore. The lawsuit essentially alleges that the working of livestock in the park damages the land, impairs the quality of water and air, threatens wildlife and limits recreational use. It questions whether ranching should take place in the seashore and demands the NPS revise or create a new General Management Plan to examine the ranching issue. A general plan amendment hasn’t taken place since 1980.

The park service undertook a Ranch Comprehensive Management Plan in 2014 following Salazar’s order and a draft plan was due last year. Needless to say, the ranchers and dairy farmers want a look at that plan. The folks suing the feds maintain the problems with the yet-to-be released management plan is that it assumes ranchers will be granted leases to continue their operations. It’s an assumption they say is wrong, since the NPS never established what the impacts of ranching and farming are in the park.

Without the 20-year lease extensions that Salazar ordered, ranchers have been working on one-year agreements, making operating businesses challenging. “Running a dairy is capital intensive,” says Bob McClure, who operates one of the historic “alphabet” ranches, I Ranch, in the seashore. He’s also president of the Point Reyes Seashore Ranchers Association. Wearing a ball cap, Ben Davis work shirt and jeans, he’s tall and quiet: “My wife works for a bank, and without a long-term lease, they won’t make a loan.”

Lunny not surprised

The ghost of the Drake’s Bay Oyster Farm controversy still hangs in the crisp coastal air. To say the struggle over whether or not Lunny and company should have been allowed to keep farming mollusks was divisive is like saying that Trump versus Clinton has caused a stir. The oyster fight set environmentalists against each other, split some advocates of the park and ruptured the community.

Kevin Lunny, whose family runs an organic cattle operation on G Ranch, says he was surprised at the timing of the lawsuit but not the filing itself. Sitting around a kitchen table at H Ranch in the park, with McClure and Julie Rossotti of H Ranch, Lunny tugs on his gray goatee and looks a little wistful. “The Park Service is in the middle of doing the RCMP [ranch comprehensive management plan],” he says, “and the lawsuit says it has to drop that to do the general plan.”

McClure’s great grandfather came to the seashore in the late 1880s and worked for various dairies in the area until he was able to purchase G Ranch in 1919. The family purchased I Ranch 20 years later. The Lunny family leased G Ranch in 1947. Rossotti’s family has been ranching in Marin County for four generations (and in the seashore for three generations).

Like any good tale, there are more than two sides in the lawsuit brought by Johnson and company. Grab a cup of coffee at Toby’s Feed Barn in Point Reyes or a beer at Smiley’s in Bolinas, and you’re unlikely to hear anybody boo-hoo for the NPS. West Marin is truly the last bastion of what this county was like even 50 years ago, meaning distaste for the government doesn’t bubble just below the surface around here, it runs deep among its residents. While the locals love their seashore, that love doesn’t extend to the bureaucracy that the Park Service has in triplicate. There’s a school of thought in the community that even though the NPS has made a public statement supporting the ranches and is fighting the legal action, the agency would honestly like the ranchers and dairy farmers to vacate the land. There will be more on the roots of this theory a little later.

While the flow of visitors to West Marin pleases merchants and feeds the local economy, those same visitors makes life harder on locals, who live in along the coast for its pastoral environment and peaceful lifestyle. And folks blame the NPS and the park for the tourists toting cameras and asking for directions.

A community in peril

A community in peril

People talk about how the lawsuit could wind up pushing the ranchers and farmers out of business, and while the economic impact isn’t a minor part the story, there’s much more. The visceral reaction has more to do with the tearing of the community’s fabric just a short time after Drake’s Bay shredded those threads. These farmers won’t just lose their paychecks if the lawsuit ends agriculture in the park, they’ll lose their way of life and the place they call home—and the community will change.

“If the lawsuit succeeds, it will be devastating,” says Laura Watt, a cultural resource management professor at Sonoma State University, where much of her research has been done on the interaction between the NPS and ranchers in Point Reyes. “It’s a very tight knit community, everybody seems like they’re related.”

The scars of Drake’s Bay are still fresh and, to a few observers, the lawsuit is simply inviting an infection that will make the coast sick all over again.

Most of the cattle or dairy operations in the park have been there since 1858. The ranches—18,000 acres worth—were purchased by the federal government for $50 million in 1962 to help create the park. The deal was that the feds would lease the land back for agricultural use to the families until the patriarchs died or the family gave up the business. In recent years, families have continued on the land under agreements lasting one, five or 10 years. The terms of land use for grazing calls for ranchers and farmers to pay as little as $7 per cow and calf, a rate critics say is well below what West Marin land outside the park would cost. The ranches make up 25 percent of the land in the 71,000-acre park.

Environmental royalty

Huey Johnson is regarded as a true warrior for the environment. He was the president of the Nature Conservancy, a co-founder of the Trust for Public Lands and secretary of resources for Governor Jerry Brown the first time around when he was dating Linda Ronstadt (Brown not Johnson). In 2009, he won the Armory Pugsley Medal for the promotion and development of parks, a substantial honor in spite of the name (which sounds like a cross between a military facility and a character from the old Addams Family TV series). He’s the sole local bringing the lawsuit against the NPS; the Center for Biological Diversity (CBD) hails from Tucson, Ariz., and the Western Watersheds Project (WWP) calls Hailey, Idaho, home.

Lest these plaintiffs be branded by opponents as carpetbaggers, the lawsuit states that CBD has “3,000 members and supporters in Marin County,” and Jeff Miller, an environmental advocate for the center, calls Marin his home and works out of its Oakland office. WWP has 1,500 members, some of whom live in the Bay Area.

These environmental advocates have a successful record of speaking on behalf of Mother Nature. CBD reports a 93 percent rate of favorable outcomes in their legal battles, and WWP counts a 2007 case in which grazing regulations across 11 states were tossed out by a federal court.

Johnson and the two nonprofits are represented by a pair of law firms, Keker & Van Nest from across the Golden Gate in San Francisco and Advocates for the West, out of Boise, Idaho. Keker’s lead attorney is Jeffrey Chanin, a Tiburon resident. The Idaho firm has a long track record of challenging the NPS on a wide variety of environmental issues.

Those who brought the lawsuit adamantly deny being anti-ranching—or anti-business, for that matter. They simply want the park service to examine the impact of ranching and dairy operations on the park. In a statement at the time the action was filed, Johnson said, “The lawsuit is the last resort to try to get the Park Service to do its job.”

The issues behind the lawsuit have been incubating for a while. In September 2014, CBD’s Miller issued a press release criticizing the Point Reyes ranchers over the tug of war regarding Tule Elk and grazing cattle in close quarters. Miller and Karen Kliz of Western Watersheds published a May 2015 story in Bay Nature titled “Cattle Grazing Is Incompatible with Conservation,” which used Point Reyes as an example of failed public policy harming undomesticated animals and the park.

Miller says his organization has been watching ranching at the seashore for 10 to 15 years. “The reality is, the National Park Service was going to issue 20-year leases without adequate environmental review of its ranch management plan or determining whether ranching is compatible with the purposes of the national seashore. It assumed ranching would continue and expand, and we’re simply asking the park service to determine what the impacts are,” he said. “There’s been overgrazing, and we’re actually quite concerned with chronic violations of existing leases by the ranchers.”

He says that ranchers sometimes have more cattle than they’re allowed, and that the demands of ranchers endanger the Tule Elk that the NPS introduced at Point Reyes in an effort to keep the species going. It’s the health of the Tule Elk that finally pushed CBD, Johnson and WWP into filing the legal action. During the drought, 250 Tule Elk that were confined to a 2,600-acre preserve within the park died, while the free roaming elk, which sometimes end up in the same pasture land as the ranchers or farmers cows, increased their population by one-third. “The deaths of the Tule Elk and rancher demands that the elk be removed were the last straws for us,” Miller said.

Miller rejects the idea that the closure of Drake’s Bay Oyster Farm was in any way tied to the February lawsuit. “The oyster farm had an agreement that ended. That was straightforward. But the National Park Service has made it abundantly clear it thought ranching should continue even though no specific agreement exists anymore. [The NPS] has been very arbitrary in how it’s proposing to expand ranching, but it doesn’t get to just decide to promote commercial activities over protecting natural resources.”

Miller was also very clear that the lawsuit his organization signed on to is not about getting rid of agriculture at the seashore, but Watt and other locals don’t buy Miller’s claim. “They have made it very clear their intent is to get rid of the ranchers, plain and simple,” she says. “Plenty of work has been done on the environment in Point Reyes and nobody ever brought a lawsuit.”

Though Johnson didn’t return calls requesting an interview for this story, in the past he’s shared his opinion in other venues, and it’s plain that the ranchers aren’t the only group that causes him upset these days. He labeled those who side with the ranchers as “a funny little cabal of dairy lovers out there. They’ve gotten well-rooted, the local press often favors them, they’re nice people and it seems like a good idea,” Johnson told the North Bay Bohemian in March. “I would say that there’s been something of a public relations war, not really a war but an ongoing struggle, and a handful of well-meaning elderly environmentalists have long ago fallen in love with the dairy cattle.”

Johnson, at 83-years of age, knows something about elderly environmentalists to be sure—and, truth be told, he doesn’t have much regard for environmentalists no matter their age. “Anybody can say, ‘I’m an environmentalist’ and pay their $10,” Johnson told E&E Publishing in March. “The environmental movement has gotten very passive in recent years. Organizations have just sunk into the landscape. Rather than defending the environment, they spend a lot of time quivering under their desks. It’s the fear of not being invited to cocktail parties.”

Manhattans, appetizers and pithy conversation aside, Johnson sees his lawsuit having an impact on other national parks if it’s successful. He says there are a number of other parks with cattle operations, and his efforts aren’t just about agriculture in Marin, because there are “powerful special interests that promote grazing on federal landscapes.” Johnson went as far as saying that ranching in national parks amounted to “welfare ranching.”

As many as 30 parks across the country, including Pt. Reyes, allow commercial grazing—not to be confused with grazing on public lands, which is administered by the Bureau of Land Management, like those made famous by Tea Party favorites the Bundy family.

NPS in the cross-hairs

NPS in the cross-hairs

One of the arguments made during the Drake’s Bay controversy, and resurrected with the new lawsuit, is that private businesses have no place in national parks. But in reality, this discussion doesn’t have much in the way of legs. According to the NPS website, there are 10 different national parks looking for businesses to operate concessions or services within their boundaries, including Point Reyes, where the agency is casting about for an operator for Five Brooks Stables and guided horseback rides.

Moreover, there are more than 500 private businesses that contract with the NPS, so a better argument might be to question the agency’s business acumen. It was recently locked in a legal action with Delaware North Corp., the former concessionaire at Yosemite Park that operated the Ahwahnee Lodge as well as Curry Village. Delaware claims ownership of those iconic names as well as Yosemite National Park, which explains why folks are now making reservations for non-smoking rooms at The Majestic Yosemite Hotel.

That rolls right off the tongue, doesn’t it?

In a cruel bit of trivia, the gentleman who made the decision to change the names in Yosemite is Yosemite Superintendent Don Neubacher, who held the superintendent post in Point Reyes during the Drake’s Bay controversy.

As you can see, the NPS is no stranger to the courtroom. Hell, the ranching lawsuit isn’t even the only one going on locally. The park service was sued in April by a group called Save Our Recreation over new regulations it intends to roll out over where dogs will be allowed in the Golden Gate National Recreation Area.

A little free advice for the NPS: You can piss off plenty of groups in the North Bay and live to tell the tale. Dog owners? Not so much.

Melanie Gunn, a spokesperson for the park, declined to comment on the February lawsuit. But at the time the legal action was filed, she said, “Ranching is here to stay at Point Reyes National Seashore. It’s an important part of our history and an active part of the seashore. The seashore wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for the ranchers.”

There are no reliable numbers that break out the value of the 13 family ranches and dairy operations in the Point Reyes National Seashore. According to the University of California Extension, Marin County agriculture production was valued at almost $101 million in 2014, the last full year of data available. That includes $73.6 million in livestock products, livestock and related goods. It’s said that 25 percent of the milk flowing out of Marin dairies comes from cows grazing at the seashore.

Though Marin agriculture has faced pressure from suburban encroachment, increasing land costs, drought conditions and a generation uncertain it wants to stay down on the farm, farmers, ranchers and marketers have succeeded at putting forth the county as a launch pad for boutique ag and food brands. Straus Family Creamery, Niman Beef and Cowgirl Creamery are solid examples how artisan food and an organic culture have teamed up to put Marin on the foodie map.

But the dollars only tell part of the story in terms of agriculture’s value in Marin and in the park. The “Farm to Fork” movement is well illustrated by local products being readily available in grocery stores, farmer’s markets and on menus in Bay Area restaurants. “Our family tradition is to produce quality food for our community,” says Rossotti. “We’re proud of the contribution we make to the local food movement in the Bay Area.”

Besides the H Ranch, Rossotti and her husband, Tony, also work their own ranch in Petaluma where they raise African Boer goats and pasture-raised Pekin ducks.

Farm fold-up fallout

Should the lawsuit succeed, one outcome could be the shuttering of the ranches and dairy farms. The animals would be removed, the families displaced and the culture of agriculture shut down in the park. “West Marin is like a tapestry,” says Sam Dolcini, president of the Marin County Farm Bureau. Dolcini’s head was made for a cowboy hat and his mustache looks like cartoon character Yosemite Sam might have had a hand in trimming it. “The thing is, agriculture and environmentalists have come from opposite directions to preserve family farms around here. But if this lawsuit ends ranching in the park, that tapestry will come loose.”

While the NPS won’t comment on the lawsuit, it did file an answer in court. It asked the court to dismiss the action, saying the suit seeks to force the agency to update its plans in a “timely manner,” but congress has never defined what a timely manner means where the NPS is concerned. The feds also took issue with the notion that the NPS erred in issuing new agreements to the ranchers without an environmental review, stating that the suit is simply a general challenge to ranching in Point Reyes. U.S. attorneys also claim that the environmental review the lawsuit is seeking would be accomplished by the ranch management plan that the lawsuit demands must be stopped in favor of a General Plan.

Lawyers for the trio of nonprofits who brought the action say the filing merely seeks to delay the legal process.

While there’s no escaping the parallels between this lawsuit and the Drake’s Bay saga, there’s one notable difference. When Drake’s Bay was fighting for its life, the community was split. While there were certainly locals firmly in the oyster farm’s camp, there were also Marinites making the vocal argument that the parks service was right and Drake’s Bay had to go.

This time around, some critics who praised the agency for sticking to its guns and ousting Drake’s Bay are siding with the ranchers. One of the most outspoken organizations in the oyster fight was the West Marin Environmental Action Committee, which was relentless in saying Lunny’s operation needed to depart. This time around, with a new executive director, the EAC is backing the ranchers. The National Parks Conservation Association, a national organization that advocates for the parks, is also advocating for the ranchers. Neil Desai, the director of field operations for the Pacific region, says ranching in the park should continue and that the oyster farm situation was far different from the lawsuit facing the ranchers. “We don’t agree with the lawsuit,” Desai says, adding that the park service was engaged in a process that would examine how ranching impacts the park, and that the legal action disrupts that work.

The axe that was used in the oyster fight is still sharp enough for Desai, however. He blames the oyster farm’s pursuit of further action in the courts for setting back the park service’s progress on the ranch management plan.

The county of Marin is also backing the ranchers and plans to join the NPS in the legal battle. Congressman Jared Huffman (D-San Rafael) has been vocal in his support of agriculture in Point Reyes, calling the lawsuit “wrongheaded” and a “fringe action.” He also said that he would stand by the county in fighting the lawsuit. Marin Agricultural Land Trust is also supporting the ranchers in the lawsuit fight, saying the future of agriculture in the county is at stake.

Democratic Senator Dianne Feinstein, who sided with the oyster farm as well, sent a March letter to Interior Secretary Sally Jewell urging the agency to move forward with the ranch management plan as well as efforts to issues 20-year leases.

Horns of a dilemma

No matter the outcome of the lawsuit, one issue that’s sure to cause controversy is how the NPS handles the Tule Elk at the seashore. The agency has a 2,600-acre preserve for the animals, fenced from the rest of the park, but from 2012 to 2014, the elk population in the fenced portion plummeted from 540 to just 286. The elk were introduced to the park in 1978 in an effort to revive the endangered species, which hadn’t existed in the area for more than 100 years. They made an impressive comeback and in 1998, the agency relocated 28 Tule Elk, let them roam free and the animals made their way to Drake’s Bay. The elk are now on the same lands inhabited by cattle, foraging the same pastures.

If Miller is unhappy about the NPS assumption that ranching should continue in the seashore, he’s beside himself over how the agency has dealt with the Tule Elk issue. In an email to NorthBay biz, he wrote about the NPS killing a number of the animals on purpose: The park service shot 20 elk from the Drakes Beach and Limantour herds last fall, ostensibly to test them for Johne’s disease. However, it hasn’t yet explained whether it could have tested the herd for disease without killing one-tenth of it—and it isn’t requiring the ranchers to test their dairy cattle for the disease, which is the most likely source of transmission of the disease to the elk. We suspect the park killed the elk to placate the ranchers. NPS also happened to kill a large number of bull elk, which are the elk most likely to have conflicts with the ranchers. We’ve submitted a Freedom of Information [FOIA] request to the park to get answers about why it’s deliberately killing elk and if the shootings will continue.”

Miller says he originally learned of the shooting of the Tule Elk in a 2014 Point Reyes Light story, and the NPS referenced the "culling" of the elk in a posting on its website pertaining to the comprehensive ranch management plan. He says his organization made its FOIA request in April and the agency says it will respond by August 31.

The National Park Service did not respond to a request for comment on the killing of the elk for this story.

CBD’s Miller says the ranchers and the NPS have the situation wrong—that the agency is obligated to manage for wildlife and natural resources in the park, not protect the bottom line of the ranchers. The center issued a press release in April 2014 faulting the agency for keeping elk fenced in an area without access to water during the drought. Miller and the CBD want the elk to roam free and for the NPS to take down fences limiting the animals, not build new ones to placate the ranchers.

The ranchers say they have a tough enough jobs keeping the cows pastured and watered without the elk helping themselves. The Point Reyes Ranchers Association has been calling for the NPS to erect fences to keep the elk from mixing with the cattle or to kill or evict free-roaming elk. For their part, McClure, Rossotti and Lunny says the elk are a problem for all the ranchers but they’re content to wait to see what the NPS propose to try to solve the problem.

The trio also said they trust the agency to defend the suit and, thus, their livelihood. This statement was somewhat surprising coming from Lunny, who engaged in a protracted knife fight with the NPS over Drake’s Bay. If any rancher has a reason to doubt the NPS’s rectitude, it would be Lunny.

That expression of faith also runs counter to an open secret in the community—that trust for the park service is not universal. SSU’s Watt says the NPS has regularly played one rancher off another in negotiating new agreements, a tactic that not only put the agency in a better position to elicit terms it wanted but also sowed some distrust among the ranchers for each other and animosity toward the federal agency. “The ranchers aren’t likely to talk about it, because they have to live with what the park service does and coexist, but this has been an issue for years,” she said. In researching her book on the park’s history, Watts found that efforts to eliminate agriculture in the park began surfacing more than 20 years ago.

Watt, Phyllis Faber (a well-respected Mill Valley environmentalist, co-founder of MALT and a former board member of the Point Reyes National Seashore) and attorney Peter Prows authored a piece in the Point Reyes Light in January 2014, putting the rumor on display. Prows is one of the attorneys that represented the oyster farm against the NPS.

The story alleged that Faber had been told by the park’s then-supervisor Neubacher that the NPS had a plan to end ranching in the park, and it started with getting rid of the oyster farm. With that operation out of the way, environmental groups would bring legal actions alleging the agricultural operations created environmental harm for the park, and that the ranchers, with limited resources, would go away.

NPS, predictably, has denied the allegation.

It remains to be seen how or even whether this current lawsuit will move forward and, if it does, what the outcome will be. But in the meantime, dairy farmers and ranchers will continue to care for their animals and the land. Looking around, Lunny begins to smile. “This place,” he repeats. “My whole life has been lived in and out of this house.”

The remark just floats in the air.

Bill Meagher is a contributing editor for NorthBay biz. He writes the monthly column Only in Marin. He is an associate editor in The Deal’s west coast office in Petaluma and has called Marin his home for almost 25 years.

Author

-

Bill Meagher is a contributing editor at NorthBay biz magazine. He is also a senior editor for The Deal, a Manhattan-based digital financial news outlet where he covers alternative investment, micro and smallcap equity finance, and the intersection of cannabis and institutional investment. He also does investigative reporting. He can be reached with news tips and legal threats at bmeagher@northbaybiz.com.

View all posts