One step through an enchanting brick entryway leads to the refreshing sounds of a mesmerizing waterfall, preceding a luscious, flowery wonderland that resembles only what children read about in fairy tales. However, this nature-filled estate is in no part a fairy tale, but captures one very real story. This is the Luther Burbank Home & Gardens, an estate located in the heart of Santa Rosa Avenue that preserves the legacy of one man that not only helped put Sonoma County on the map, but changed the history of plant science. And this year, Sonoma County will celebrate the 170th anniversary of Luther Burbank’s birthdate.

The early days

Luther Burbank was born on March 7, 1849, in Lancaster, Mass., to Samuel and Olive Burbank. He was the 13th of 15 children and his mother’s first surviving child. Burbank’s father was a brickmaker and his mother was a homemaker. He became enthralled by the world of nature at a young age. His fascination was originally inspired by his cousin, a curator at a Boston museum, and his uncle’s friend, naturalist Louis Agassiz, though it’s not known whether the two ever met.

Though Burbank attended high school, he never had the opportunity for formal scientific career training at  a university. However, he didn’t let the lack of academic preparation stop him from creating his own experiments, producing his own inventions and forming his own theories. Instead of looking to professors for knowledge and inspiration, Burbank’s main influences included the works of Charles Darwin, especially The Variations of Animals and Plants Under Domestication. “He found that if plants were changing over time, he wanted to use some of those natural laws to help better plants,” says historian Rebecca Baker, an archivist who has worked at Luther Burbank Home & Gardens for 20 years.

a university. However, he didn’t let the lack of academic preparation stop him from creating his own experiments, producing his own inventions and forming his own theories. Instead of looking to professors for knowledge and inspiration, Burbank’s main influences included the works of Charles Darwin, especially The Variations of Animals and Plants Under Domestication. “He found that if plants were changing over time, he wanted to use some of those natural laws to help better plants,” says historian Rebecca Baker, an archivist who has worked at Luther Burbank Home & Gardens for 20 years.

At age 21, Burbank purchased his own 17-acre property in Massachusetts, where his plant-breeding career officially took flight. “In general, he was a very keen observer, and had a good eye for identifying useful and novel phenotypes,” says Rachel Spaeth, plant geneticist and garden curator for the Gardens. “He did a lot for advancing plant-breeding technique and opening people’s eyes to other things that were available.” Burbank’s keen eye soon led him to his “Burbank seedling” potato strain, one that he is most widely known for propagating from a rare seedball. However, he sold the rights to his famous potato for $150, earning enough for him to move from Massachusetts.

California bound

“His brothers knew he loved plants, so they would write home to him (after moving to California themselves) and embellish quite a bit. They were telling him we have a 12-month growing season, which we don’t,” adds docent Ron Powers with a laugh. “So, they enticed him into coming out [here].” He relocated to California, living in Marin and Sonoma counties before permanently settling in Santa Rosa in 1877.

Burbank bought the four-acre property in Santa Rosa for a mere $2,000 in 1877, sharing the house and property with his mother and sister. In 1885, he bought another 18-acre property in Sebastopol, which became known as the “Experiment Farm.” That property now consists of about 5 acres, run by volunteers of the Western Sonoma County Historical Society. He married his first wife, Helen Coleman Burbank, in 1890. The two remained married for six years before divorce. According to Powers, the couple simply did not get along, resulting with Burbank sleeping in his office room much of the time. They eventually parted ways.

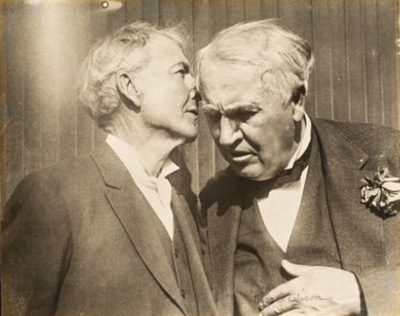

In 1916, he married Elizabeth Waters, who was once his assistant. Then, in 1906, just before the earthquake, he built another house on his property. He and Elizabeth resided there until Burbank’s death. The house was removed during an urban renewal in the 1960s. Throughout his horticulture career, Burbank met and befriended multiple prestigious historical figures while living in Sonoma County such as Thomas Edison, Jack London and Henry Ford, all of whom spent time in Burbank’s home. Photographs of their gatherings are displayed throughout the living room in his home. One picture illustrates Burbank handing a bouquet of his Shasta daisies to Helen Keller beneath his beloved Cedar of Lebanon tree.

Burbank often referred to Santa Rosa as the “Chosen Spot,” for the city was amidst the perfect environment for plants to flourish. According to Powers, Burbank wrote home often before his family came to California, raving about the enchanting climate. Oddly enough, he didn’t want them to spread the word, fearing less desirable folks would move to Santa Rosa.

During his career, Burbank used hybridization and selection with tens of thousands of distantly-related plant varieties to create favorable genetic anomalies. His results came from his self-taught theory and principles. “Some of his experiments were not well received by the scientific community,” says Spaeth. [For example,] they didn’t believe he cross-bred a plum and an apricot, until after he died.” Aside from introducing new plant species, Burbank also helped further establish the use of imports, bringing new crops to California’s rich soil. In fact, he was an early importer of kiwi.

During his career, Burbank used hybridization and selection with tens of thousands of distantly-related plant varieties to create favorable genetic anomalies. His results came from his self-taught theory and principles. “Some of his experiments were not well received by the scientific community,” says Spaeth. [For example,] they didn’t believe he cross-bred a plum and an apricot, until after he died.” Aside from introducing new plant species, Burbank also helped further establish the use of imports, bringing new crops to California’s rich soil. In fact, he was an early importer of kiwi.

In 1893, the publication of his plant catalog, New Creations in Fruits and Flowers, made him well known around the globe. Though the majority of Burbank’s accomplishments were underestimated by the professional science community during his lifetime, he received one of the nation’s highest honors by earning a large-scale grant—$10,000 a year—from the Carnegie Institution of Washington in 1906. Unfortunately, this great achievement turned into Burbank’s greatest failure after losing the grant halfway through its tenure, due to insufficient written reports of his findings.

In the second half of his career, Burbank collaborated with producers of a 12-volume publication of Luther Burbank: His Methods and Discoveries and Their Practical Applications, which was released to public in 1914. Today, the scientific community continues to discover the value of some of Burbank’s work. The 12-volume set is not considered “scientific” writing, but it explains some of his plant experiments, successes and failures in an easy-to-understand way for everyday horticulturists.

A career based on experimentation

Burbank’s entire career was based on experimentation, as opposed to playing by set rules. By cross-pollinating both native and invasive species, he created hybrids to contrast certain characteristics. Though he never worked in the grape-growing industry, his work will forever be significant in the greater Santa Rosa area and in the world as a whole. During his lifetime, he developed at least 800 new successful strains, but there are only a few that he is most famed for producing.

The Burbank Potato was his first major creation, and is most significant for its strong disease-resistant quality. Burbank strived to produce a potato that would defend against the blight that caused the Irish Potato Famine, which wiped out at least 75 percent of what was initially an essential staple crop until the famine hit in 1845. With his genetically reborn Russet, he succeeded in exactly what he set out to do. The version available today, a variant of Burbank’s original potato, is the Russet Burbank, used widely as a baking potato and for French fries. Today, the Russet Burbank is $1.5 billion industry for growers. Another creation he was known for is the plum. “I would say his [greatest] legacy is the Santa Rosa plum, which is considered the major pollinator for all other plums,” says Spaeth. “It’s become the standard in the industry, and the plum is the most commercially and economically important of his creations.

”Initially, introducing plums you could eat fresh in California was extremely difficult. The primary  challenges to commercializing plums in an era without refrigeration and motor vehicles were shelf life and shipping quality. As a result, prunes were a more favorable commodity in the market. In the 1850s, the first prune-plums came to California from Europe. More than three decades later, Burbank read about “the blood plum of Satsuma,” a red-fleshed, fresh eating plum from Japan. He wrote to a plant exporter in Japan and requested seeds from the tree. In 1886, Burbank introduced several cultivars of plum from the seed stock, including one he called “Satsuma” and another called “Burbank.” These varieties as well as the others received were prominently used in his breeding experiments that ultimately resulted in several award-winning plums such as Santa Rosa, Wickson and Beauty. By the end of his life, Burbank introduced more than 100 different cultivars of plum, completely changing the human perception of this fruit. “People eat the Santa Rosa plum, but it’s also important economically because it’s used as a pollinator for a lot of other plums that are grown,” says Baker.

challenges to commercializing plums in an era without refrigeration and motor vehicles were shelf life and shipping quality. As a result, prunes were a more favorable commodity in the market. In the 1850s, the first prune-plums came to California from Europe. More than three decades later, Burbank read about “the blood plum of Satsuma,” a red-fleshed, fresh eating plum from Japan. He wrote to a plant exporter in Japan and requested seeds from the tree. In 1886, Burbank introduced several cultivars of plum from the seed stock, including one he called “Satsuma” and another called “Burbank.” These varieties as well as the others received were prominently used in his breeding experiments that ultimately resulted in several award-winning plums such as Santa Rosa, Wickson and Beauty. By the end of his life, Burbank introduced more than 100 different cultivars of plum, completely changing the human perception of this fruit. “People eat the Santa Rosa plum, but it’s also important economically because it’s used as a pollinator for a lot of other plums that are grown,” says Baker.

Burbank is also known for the Shasta daisy. As a child, he fell in love with the wild daisies that grew right outside his home. As an adult, he wanted to continue the memory of his favorite flower by creating a better version of it. However, instead of just any wildflower, he wanted a daisy that would be large, purely white, sturdy, one that would bloom early on in the year and persistently. Burbank crossbred four different daisy species to produce his famous Shasta. This process took 17 years, says Powers. After letting a natural pollination process occur, he selected offspring from these plants to breed with those of the English field daisy, a larger flower. The offspring from these combinations were then cross-pollinated with the Portuguese field daisy, and these seeds were bred for six years before Burbank moved to the final stages of his hybridization. Burbank took the offspring from the three conjoined flowers and pollinated them with the Japanese field daisy, one that would give the final product his desired white hue. He formally introduced the Shasta daisy, a quadruple hybrid, in 1901. He named this flower after Mount Shasta because of its snowy-white complexion. Since then, the daisy is mainly used as a garden flower.

A legacy left behind

Following a heart attack, which he survived, Burbank experienced complications and died on April 11, 1926. He did not want a stone to mark his burial plot, so he was buried beneath his beloved cedar tree in his front yard. The tree eventually became diseased and was removed in 1989, but his remains are still in the front yard area. More than 90 years following his death, Burbank is still remembered by Sonoma County and the horticulture community. And his legacy continues throughout the nation, leaving behind his crop selections and the outstanding results of his genius ideas.

“His legacy [will] live on because much of his work became the foundation for modern plant breeders. His free-form hybridization of distantly-related species and thinking outside of the box expanded textbook knowledge, rewriting what classically-trained scientists perceived as possible,” says Spaeth. “Burbank set the stage for a lot of people. With climate change, we need to use all the tools in the kit, and genetics is one of those tools. It’s essential for us to move forward and survive.”

“Burbank had a legacy of experimentation and exploration, and he had the idea that he could learn through his experience with plants,” adds Baker. “The skills of observation and experimentation are extremely important for people, and his work is inspirational to modern horticulturalists.” As for the future, perhaps his legacy will inspire modern-day horticulturists. “The only thing I can hope for is that somebody like him will come along [once again],” says Powers. “I wish he had mentored several people. He imparted a lot of good qualities.”

Burbank’s Santa Rosa Home

A National Historic Landmark

Luther Burbank Home & Gardens is a registered city, state and national historic landmark—the only site designated as such in Santa Rosa. The Burbank property includes the home, carriage house, greenhouse and living museum on 1.6 acres. Today, it’s owned by the City of Santa Rosa, and the programs are operated by the Luther Burbank Home & Gardens Association, a nonprofit organization. The site is one of only 15 horticultural landmarks in the United States. After Burbank died, Elizabeth moved into the original home and made renovations on the household, but managed to keep a vintage style throughout, upholding its original look. The living room, located at the front entrance, is filled with rugs and furniture that Elizabeth obtained from rummage sales, and the photographs on the walls display Burbank’s successes. The kitchen, once sporting a wood-burning stove and an icebox, contains modern appliances. Elizabeth had electrical appliances, but the vintage refrigerator and gas stove were donated when the home was opened to the public in 1979.

More recently, four Oriental carpets were donated to protect the redwood floors. However, most of the contents of the charming house are the original furnishings of Elizabeth. On the north-facing wall sits the “California cooler,” which is a closet that sits on this particular wall so it will not be exposed to direct sunlight. Thus, it stays particularly cool to preserve fruits, vegetables and any leftover food from previous night’s dinner. Though visitors aren’t usually shown the upstairs portion of the house due to fire safety rules, the second floor includes three bedrooms and a bathroom. Interestingly, it’s not so simple to maneuver upstairs as the ceiling is surprisingly low. During the time period, first floors were typically designed with higher ceilings to allow for a gracious, open space for guests; second floors were designed with lower ceilings to save on building costs and heating.

Arbor Week

Instead of hosting a traditional cake-filled celebration, people around the county gather for a “tree-planting party” to keep his love for nature alive. California celebrates “Arbor Week” to coincide with Luther Burbank’s birthday, which was first declared by the state in 1909. Luther Burbank Home & Gardens is holding a tree-dedication party in the gardens on Thurs., March 7, at 10 a.m.

For more information, visit www.lutherburbank.org.

This year, the City of Santa Rosa will also hold a party Sat., March 9, from 9 a.m. to Noon in two separate locations: Mesquite Park (on Mesquite Drive) and Northwest Community Park (on Steele Lane) in Santa Rosa.

For more information, go to www.srcity.org/calendar.