Warren Winiarski, creator of the Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars Cabernet Sauvignon that bested its French counterparts in the famed 1976 Paris tasting, sits up straight, rising from a relaxed position on his comfortable-looking white chair when asked to recall his days as an apprentice winemaker in Napa Valley. He speaks with intention, placing emphasis on every word. Behind him, the Stag’s Leap vineyards are clearly visible through a row of magnificent windows stretching the length the living room. “I learned one of the most important things: No detail is too small to not be considered. Every detail, you should think about it. Because it will make a difference.”

A fateful day

If only the details about the Paris tasting held up over time, as Winiarski’s convictions have. Since that fateful day more than 40 years ago, when a Cabernet Sauvignon and a Chardonnay crafted in Napa Valley notched surprise victories over French wines on foreign soil, the famed blind tasting has become as much legend as recorded history. Was it the Judgment of Paris, as coined by Time magazine? Or, was it intended as a friendly celebration of the United States’ bicentennial anniversary? Did Steven Spurrier, the founder of Academie du Vin, a wine shop and school in Paris, work alone in organizing the event, or did he have unheralded, and essential, help along the way?

It’s a tale told from various perspectives. We know for sure, however, that the Paris tasting put California winemaking on the map. And there’s one question certainly worth pondering: As the evolution set forth by the Paris tasting carries on, how do North Bay wines continue to add to the greatness of that day?

Just one reporter was on hand at the famed tasting, Time magazine’s George Taber. His piece for the June 7, 1976, edition of the magazine must’ve seemed hardly noteworthy to the editor, running only four paragraphs, without a byline for the writer. It was crammed into the issue’s “Modern Living” section, just one-third the size of the tire advertisement it shared a page with, featuring sports stars Roger Staubach, Tom Watson and Arthur Ashe. While there was no comment from either Winiarski or Miljenko Grgich, who crafted the winning Chateau Montelena 1973 Chardonnay, Taber did reach Jim Barrett, owner at Montelena. When asked to comment on the outcome, he quipped, “Not bad for kids from the sticks.” Napa Valley certainly isn’t considered the “sticks” any longer, but more on that later

Barrett was possibly the easiest for Taber to contact since he was in France at the time, on a wine tour led by longtime Napa resident, Joanne DePuy. Incredibly, legendary Napa Valley winemaker André Tchelistcheff was on the tour as well. It was the good fortune of Spurrier, who was originally named by Taber as the event’s mastermind, that DePuy’s tour coincided with the tasting; he was afraid he couldn’t get all of the American wine through customs. “Steven called me and said, ‘Help — can you get this wine through? I can’t get it through,” says DePuy. She called her friend at the San Francisco Wine Institute, who said that since each passenger is allowed two duty-free bottles, she could distribute the haul amongst her tour members, of which there were more than 30.

The wine made it safely to Paris, save for one mishap. “TWA handled it very carefully, and when we got to Charles de Gaulle airport in Paris, which had just opened at the time, Steven was there to meet me. We were standing there talking, and he had a vessel to carry it in, a pushcart. I actually smelled the wine before we got it,” says DePuy. “We got the three cases, and one of them showed that something had broken. Steven was very nice about it. I found out much later, certainly not on the tour, but only one bottle had broken. He had purchased two bottles of everything, so that one was covered.” And thanks to DePuy, Spurrier’s plans carried on.

Spurrier first met DePuy while touring with her company, Wine Tours International, in Napa. She took him to Chateau Montelena and Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars, among other places, though neither Winiarski nor Grgich had a clue about Spurrier’s intentions. “All I knew, Spurrier came and bought the wine and it was going to be in a tasting,” says Winiarski. “His associate had come before and she was impressed with the wines. It’s on her recommendation that Steven came and bought two bottles.” According to Winiarski, Spurrier’s associate was Patricia Gastaud-Gallagher, an American journalist and wine aficionado living in Paris.

In fact, according to the San Francisco Chronicle, the tasting was Gastaud-Gallagher’s idea, not Spurrier’s, as is conventional wisdom. The Academie du Vin hosted yearly tastings of American wines at Gastaud-Gallagher’s urging, and with the U.S. celebrating its bicentennial anniversary in 1976, she was determined to hold a tasting with hard-to-acquire American wines she considered exceptional, such as those found in Napa. Her vision wasn’t a competition, but rather an event to share what they found in Napa with wine revelers in France whom she and Spurrier respected.

Two weeks before the tasting, however, Spurrier thought to offer the wines alongside each other in a blind competition, according to a 2016 Time article. Taber’s headline from the original Time story of four paragraphs read, “Judgment of Paris,” cementing the event’s history as a competition, despite its original intention as friendly celebration. As Gastaud-Gallagher said, according to Mobley, “They were tasters. They became ‘judges’ once George Taber reported it. The bicentennial tasting was my work with Steven. The ‘Judgment of Paris’ was Steven’s work with George.”

Two weeks before the tasting, however, Spurrier thought to offer the wines alongside each other in a blind competition, according to a 2016 Time article. Taber’s headline from the original Time story of four paragraphs read, “Judgment of Paris,” cementing the event’s history as a competition, despite its original intention as friendly celebration. As Gastaud-Gallagher said, according to Mobley, “They were tasters. They became ‘judges’ once George Taber reported it. The bicentennial tasting was my work with Steven. The ‘Judgment of Paris’ was Steven’s work with George.”

While the tasting made Spurrier famous, the contributions of DePuy and Gastaud-Gallagher are often lost in the shuffle, though Taber’s book, Judgment of Paris, gave them their due.

Gastaud-Gallagher’s career was exceptional without the fame. She gained a degree as an enology technician and went on to pen influential wine columns in France. Additionally, she served as academic director of Le Cordon Bleu in Paris, a famed hospitality and culinary school.

DePuy was a pioneer in her own right, influencing an industry dominated by men. She was the first woman to address the Napa Valley Vintners Association and continued to connect the world through wine, convincing former California Secretary of State March Fong Eu to lead a wine tour to China. As for her tour’s role in the Paris tasting, the effects are still felt to this day. “It makes me feel very happy that I had a part in the tasting,” says DePuy. “It’s very satisfying.”

Culture clash

DePuy also had a front row seat for Barrett’s reception of the news, as well as for the reaction of Tchelistcheff, since they were both on her tour. Winiarski and Grgich, whose career paths intertwined on occasion, each worked with Tchelistcheff, the groundbreaking, Russian-born, Napa Valley winemaker. “We were at Château Lascombes,” says DePuy, referring to the famed winery in the Margaux appellation of France’s Bordeaux region. “They had about 40 or 50 winemakers from Bordeaux that gave a luncheon for the 33 of us that were visiting. One of the staff members came up to me and said, Monsieur Barrett was wanted on the telephone and asked if I could get him and follow him.” DePuy worried that it was bad news because only Pierre Brejoux, Inspector General of the Appellation d’Origine at the time (and also an expert taster at the Paris tasting) knew they were at the Château. “I followed him around a path around some buildings. We went into a small room. Jim had to get down on his knees to talk on the phone; it was on a little table. He was talking and nodding his head and then he looked at me and circled his forefinger and thumb, in an ‘okay’ gesture, so I left. He then came back and whispered in my ear that it was Time magazine, and that he had won the tasting in Paris. And Warren had won, too.”

DePuy also had a front row seat for Barrett’s reception of the news, as well as for the reaction of Tchelistcheff, since they were both on her tour. Winiarski and Grgich, whose career paths intertwined on occasion, each worked with Tchelistcheff, the groundbreaking, Russian-born, Napa Valley winemaker. “We were at Château Lascombes,” says DePuy, referring to the famed winery in the Margaux appellation of France’s Bordeaux region. “They had about 40 or 50 winemakers from Bordeaux that gave a luncheon for the 33 of us that were visiting. One of the staff members came up to me and said, Monsieur Barrett was wanted on the telephone and asked if I could get him and follow him.” DePuy worried that it was bad news because only Pierre Brejoux, Inspector General of the Appellation d’Origine at the time (and also an expert taster at the Paris tasting) knew they were at the Château. “I followed him around a path around some buildings. We went into a small room. Jim had to get down on his knees to talk on the phone; it was on a little table. He was talking and nodding his head and then he looked at me and circled his forefinger and thumb, in an ‘okay’ gesture, so I left. He then came back and whispered in my ear that it was Time magazine, and that he had won the tasting in Paris. And Warren had won, too.”

Tchelistcheff’s connection to Winiarski and Grgich was not lost on DePuy. “So I said, ‘I will tell Andre immediately.’ When I went over and whispered to Andre, he said, ‘Don’t tell a soul. Don’t tell anyone while we are here at the winery.’” According to DePuy, Tchelistcheff thought it would embarrass their hosts to revel in Napa Valley’s big day while at the luncheon. “So, we didn’t say a word. But the news spread among us, and when we got on the bus three hours later, everyone hooped and hollered as soon as we were out of sight. It was jubilant. Everyone jumped up and hugged Jim and shouted. Everyone hugged Andre because he taught both Mike and Warren. We were terribly pleased about it.”

DePuy’s tour took the high road, with Tchelistcheff’s leadership, though it was apparent to DePuy that the French simply weren’t ready for the monumental changes that had just been set in motion. “At that luncheon, I was seated on the right of Alexis Lichine (a Russian wine writer and then part owner of Château Lascombes) and Andre was on his left. When he gave his talk, the gist of what he said was that Americans are doing a good job and will soon be making nice wine. I mean, it was quite condescending.”

DePuy’s tour took the high road, with Tchelistcheff’s leadership, though it was apparent to DePuy that the French simply weren’t ready for the monumental changes that had just been set in motion. “At that luncheon, I was seated on the right of Alexis Lichine (a Russian wine writer and then part owner of Château Lascombes) and Andre was on his left. When he gave his talk, the gist of what he said was that Americans are doing a good job and will soon be making nice wine. I mean, it was quite condescending.”

As the news spread, confidence throughout the winemaking world grew. The secret was out: French winemakers aren’t the only ones who can produce top-flight vino, and it was apparent that Napa Valley’s varietals were better than ‘nice.’ The wine industry in the North Bay began to grow like never before. “The Judgment of Paris proved that Napa Valley soil could not only make wine as good as the French, but better than the French,” says Grgich. And according to DePuy, “It certainly opened the doors to not only Napa and the United States, but to Argentina and Chili and to South Africa. It opened the doors to the wine world, really.”

Napa to Sonoma, and back again

“France thought they were top dog. Nobody could challenge that before,” says Katey Bacigalupi, assistant tasting room and wine club manager at Bacigalupi Vineyards in Healdsburg, a producer of winegrapes, and now wines, for more than 60 years and three generations. Fruit from its vineyard made its way to France in 1976, as a component to the 1973 Chateau Montelena Chardonnay crafted by Grgich.

Helen Bacigalupi, founder of Bacigalupi Vineyards along with her husband, Charles, offered this memory: “I remember it was the Fourth of July. Charles was off sailing, so I was home by myself. I thought that since it was our nation’s birthday, I would bake a cake. I got a call that afternoon from Mike Grgich, and he asked if I had heard the news.” Bacigalupi said no, she hadn’t heard, and Grgich told her all about it. “I said, ‘Well isn’t that wonderful.’ I think no one really knew what it meant at the time, and it was a very important event for not just Sonoma County but our family as well.”

For Winiarski and Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars, the win was also a welcome surprise. “My wife called me and said that there was a tasting in Paris,” says Winiarski, who sold Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars, but still lives in the residence he rebuilt near the property. “I didn’t think of the significance because I didn’t know anything about the tasting. It’s always nice to win a tasting, any place. I certainly didn’t know who the tasters were. I didn’t know what other wines were in the tasting until the next day.”

Chateau Montelena (the late Jim Barrett in particular) heard the news first from Taber, and led by Jim’s son, Bo, it continues to ride the wave of New-World wine set in motion by the Paris tasting. “There’s certainly a lot to learn from the past,” says Matthew Crafton, winemaker at Montelena. “We see the spirit of our predecessors in our values today. We’ve always been very confident in who we are and what we make, continuing to push the envelope with unrelenting drive and integrity. Those qualities have continued to catalyze our success around the world, now 40-plus years removed from Paris and after almost 50 years of Barrett ownership.”

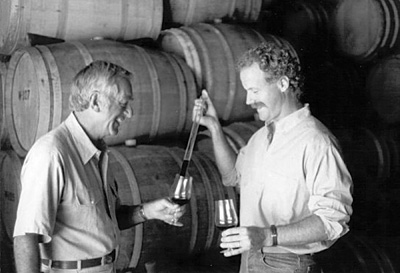

Grgich and his family, led by his daughter, Violet, still produce world-class Napa Valley wines at Grgich Hills Estate, where Violet is president. Both Grgich, 96, and Winiarski, 91, not only each learned from Tchelistcheff at Beaulieu Vineyards in Rutherford, but they both broke into winemaking at Souverain Cellars, founded in Napa’s Howell Mountain area by Lee Stewart before moving to Sonoma County’s Alexander Valley in 1973. (It was Stewart who instilled Winiarski’s attention to detail.)

The two men also both made stops at the renowned Robert Mondavi Winery in Oakville on their way to becoming living legends in the industry. Today, a bottle of the 1973 Chateau Montelena Chardonnay and the 1973 Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars Cabernet Sauvignon are on permanent display in the Smithsonian National Museum of American History’s “FOOD: Transforming the American Table, 1950–2000” exhibition.

From the “sticks” to a world leader

Barrett’s comment about being some “kids from the sticks” rang true at the time. The New York Times came to the North Bay to interview Grgich after the tasting’s results, and they described Napa as “eerie.” Now it’s bustling with wineries, residents and tourists. DePuy, a Napa resident since 1949, describes the evolution this way: “It was kind of a backwater type of place. But it was absolutely beautiful. It’s amazing how much it changed. When I first traveled in Europe, people would say, ‘Where are you from?’ I would say, ‘San Francisco’ because they didn’t know the Napa Valley. And now, any place in the world that you go, they’ve heard of the Napa Valley. It’s amazing for that to have happened in my lifetime.”

What if the tasting never took place? It almost didn’t, after all. “So much of that Paris tasting depended on chance,” says Winiarski, who was awarded the prestigious James Smithson Bicentennial Medal from the Smithsonian late last year. “So much could have been different, and it never would have happened. Even the wine getting there.”

What if the tasting never took place? It almost didn’t, after all. “So much of that Paris tasting depended on chance,” says Winiarski, who was awarded the prestigious James Smithson Bicentennial Medal from the Smithsonian late last year. “So much could have been different, and it never would have happened. Even the wine getting there.”

According to Crafton, the inevitable would have been merely delayed. “By 1976, the potential was there and the foundation for the future of American wine was set. If Montelena and Stag’s Leap hadn’t broken the barrier, it certainly would have happened soon thereafter to another winery or region. The New World was going to break out at some point. We were fortunate to be the tip of the spear.” It’s anyone’s guess, however, as to when that point would have been.

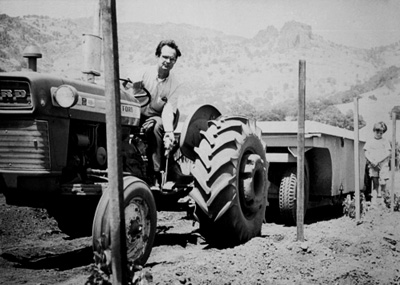

Regardless, the challenge now is to continue evolving in a positive way. Back in 1968, before he planted the first winegrapes at Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars, Winiarski realized the importance of maintaining the land in Napa Valley for future generations, helping to establish the Napa Valley Agricultural Preserve, which set the stage for sustainable wine industry growth in the North Bay. “I wanted to be sure agriculture could survive and didn’t become like Santa Clara,” says Winiarski. “It’s the resource I’m worried about now. When I got here there may have been 20 wineries. Now, there are more than 500 members in the [Napa Valley] vintners association.”

As other potential needs from land arise, such as the increasing demand for housing, and competition with cannabis growers for labor increases, wine must continue to inspire, as it did in 1976. “To this day, Napa Valley winemakers have maintained the reputation of making high quality wines, which is very important,” says Grgich.

Winiarski agrees, but adds that there are still lessons to take from the past. “I think science is helping. [UC] Davis is always thinking about new things. There’s a danger in that, too. With such advanced technology, it’s easy to go too far. If you have a powerful tool, the ability to make a big swing is given to you. That big swing could be a big mistake.

“If you have a loud voice, a very loud sound, the possibility of deafening is there. Beauty and excess don’t go together. Fatigue is a possibility because humans are capable of fatigue of excess. Excess destroys the beauty. So you have to be very careful when you have all these powerful tools. The ability to stray is very real. The beauty becomes hidden. It’s overwhelmed. Winemakers have to ask themselves, what state of soul do you want a person to have after tasting your wine? What do you want them to feel? Ask yourself that question.”

The future of Wine Country

Regarding sustainability, Sonoma County currently leads the way, with its vineyards nearly 100 percent sustainable as of September last year, according to The Napa Valley Register. The same report also notes that Napa Valley is currently 55 percent sustainable. “It’s always been important,” says Bacigalupi. “If we weren’t a sustainable business, we wouldn’t be here almost 65 years later. We’ve always had environmentally sensitive programs in place.”

Winiarski says the Napa Ag preserve still works, but more questions remain. “Are there limits that will preserve the future? The resources we have here, the potential for greatness … there are differences of opinion about how far that can go. How far can the resources be stretched? We have to answer that question. We have to face it honestly. How far can the resource be developed without endangering its health?”

Wine Country—which much like Grgich’s Chateau Montelena Chardonnay, features both Sonoma and Napa counties—clearly isn’t “the sticks” any longer. It’s a world leader, and must continue to be so, not just in wine production, but in shaping the future. The industry is well on its way, by producing the world’s finest wine with sustainability in mind.

But in keeping pace with other options in the market such as beer, spirits, spiked seltzer and even marijuana-infused beverages, wine still has a unique beauty—valued by Tchelistcheff and imparted to Winiarski and Grgich—which distinguishes itself from the field. “You want them to be elevated. It has the aspect of its structural beauty that comes before the effect of alcohol,” says Winiarski. “That kind of combination doesn’t come with anything else. It has unique capabilities to express something that I call completeness. It’s the unique capacity that wine has.”

That realization, along with dedication from countless Wine Country players and workers behind the scenes, was the inspiration behind the wine that shocked the world on the U.S. Bicentennial. As Wine Country progresses, the Paris tasting will always have its place in history and in shaping the industry. It was a perfect storm that set the North Bay on its winemaking destiny. Forty-plus years after that famed event, the future has the same potential it did back then, waiting to be shaped by the winemakers and those working in the industry today.