No one knew where SARS CoV-2, a microscopic, spike-studded coronavirus, was headed when it started its journey around the world in December 2019. It was a mystery when the first cases of a previously unseen pneumonia-like disease appeared in Wuhan, China, that month, but the virus spread easily and rapidly, infecting more than 96 million people worldwide by the end of January 2021, even reaching Antarctica.

The first cases in the United States were diagnosed in January 2020, and by mid-March, the virus had a firm grip on the country. Marin, Napa and Sonoma counties issued shelter-in-place orders in an attempt to contain its spread, and regular, everyday life came to a standstill. One year later, SARS CoV-2 is hanging on, and life still hasn’t returned to normal. We’ve seen successes and failures in the course of a year, but at the same time, medical researchers have acquired a substantial amount of knowledge. The quest to learn more continues as we fight to overcome a relentless virus.

What we’ve learned

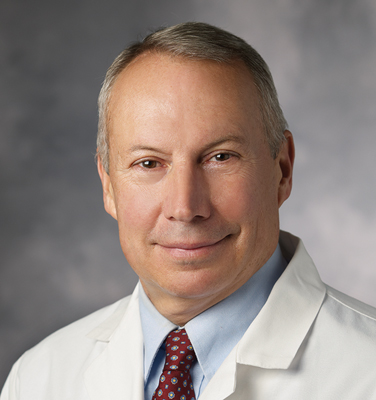

SARS CoV-2—Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome—is the second coronavirus of its type, and it causes the disease COVID-19. It originated in wild animals, most likely bats, which passed it to other animals, possibly pangolins, allowing it to jump to humans. Because its source is animals, the virus is unpredictable and can’t be eradicated, making efforts to stop it from spreading essential. The virus is transmitted very easily through tiny aerosol particles that are smaller than droplets, explains Dean Winslow, M.D., professor of medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases and Geographic Medicine at the Stanford University School of Medicine.

Individuals become infected when they inhale them, and the little spikes that are characteristic of the virus bind to cells in their airways and begin to replicate. Infected individuals spread the virus when they exhale virus-laden aerosols, which remain suspended in the air, sometimes for several hours. Winslow estimates that 60 percent of people who become infected have no symptoms and are unaware they are shedding virus. That’s why maintaining 6 feet of physical distance and wearing masks play such a large role in preventing transmission.

Until recently, no one knew how long people who had contracted COVID-19 and recovered were immune. Then in January, Public Health England released the results of a study showing that immunity lasts for five months. Winslow explains, however, that even though neutralizing antibodies persist for five months, recovered patients who no longer have neutralizing antibodies could still have some degree of protection from reinfection due to the persistence of cellular immunity to SARS CoV-2. “We just don’t know yet,” he says.

It’s normal for viruses to mutate, because they naturally evolve, as do all organisms and pathogens that affect humans. Mutations are copying errors in the genomes of a virus. “If you’re a pathogen, you actually want to develop mutations that allow transmission from one host to another,” says Winslow. He explains that if a virus completely takes over a host, it risks killing it, which isn’t a good strategy for its survival. He explains that even without drugs or much intervention, outbreaks of deadly diseases such as Ebola go away in a few months because they kill the host quickly. The first variant of SARS CoV-2—B.1.1.7—emerged in Britain at the end of December, and since then other variants have appeared in South Africa, Brazil and California. B.1.1.7 contains 23 mutations that make it more transmissible, including a change in the shape of the novel coronavirus’ spikes, allowing them to bind to human cells better. While it takes hold more easily, B.1.1.7 doesn’t seem to cause more severe disease, however, and Winslow describes that as a good strategy for a virus. “I think new variants will continue to emerge until we get it under control,” he says. Realistically, that means we should expect to see more of them.

While scientific research has contributed to a greater understanding of the virus and how it behaves, physicians have become more knowledgeable about patient care. “Medical personnel have become better at treating cases,” says Winslow. He reports that while ventilators were common early in the pandemic, doctors have found that using high-flow oxygen instead is often equally effective. They have also discovered strategies to help people cope. “Proning patients when they’re having trouble maintaining oxygen saturation is often helpful,” he says, referring to the practice of lying patients down on their stomach. In addition, the blood of patients infected with the coronavirus tends to clot more actively than those with other conditions, so doctors sometimes prescribe prophylactic doses of an anticoagulant, typically enoxaparin, to prevent complications. The use of therapeutics has evolved as well. Remdesivir showed early promise and has a modest effect, but it doesn’t appear to reduce mortality significantly. In addition, British researchers conducted a large, randomized trial of dexamethasone, a steroid drug, and the trial showed that patients with moderate to severe disease benefitted. “That was a big advance,” says Winslow. On the other hand, convalescent plasma and monoclonal antibody treatments have produced only modest results.

Vaccines

The greatest breakthrough is the development of vaccines. The FDA issued Emergency Use Authorization to Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna for their vaccines in December, and several others are in the pipeline. Both vaccines use messenger RNA (mRNA) and are similar in structure. RNA is a single thread of a genetic code that cells read and use to create protein. Developers create a vaccine by using a tiny amount of genetic material coding for the spike protein that is large enough to provoke an immune system response but too small to create a virus. When the vaccine is injected into an individual’s arm, the mRNA causes the muscles around the injection site to create a piece of the virus’ spike protein.

The foreign material then activates the immune system, which recognizes an invader and attacks it as though it were the disease, thus creating immunity. Recipients of the vaccine might experience soreness and moderate side effects, and those are good signs, because they show the vaccine is doing its job, teaching an individual’s cells to recognize and fight the virus that causes COVID-19. Both vaccines require two doses several weeks apart. Researchers have not yet determined how long immunity will last but hope it will provide protection for at least a year. “Both messenger RNA vaccines are very safe and 95-percent-plus effective,” says Winslow.

A significant number of people must be inoculated to achieve herd immunity, and with the exception of people who have had previous anaphylactic reactions, Winslow knows of no contraindications to deter people from getting the vaccine. He reports that 70 to 80 percent of the population needs to be vaccinated to achieve herd immunity. In a country of roughly 330 million people, 248 million must be vaccinated to meet this goal. At press time, just 6.5 million Americans had received both doses of a vaccine, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). However, slightly more than 27 million people had received at least the initial dose. Additionally, President Joe Biden and his new administration opened the federal government’s first mass vaccination sites in California, in a partnership of FEMA and the Governor’s Office of Emergency Services, finally putting the strength of the national government behind inoculation efforts.

Meanwhile, we need to be good citizens and keep practicing safety measures until we’ve reached this massive goal. “Natural infection would be terrible,” he says, noting that many deaths would occur, and hospitals would be overwhelmed. He encourages people to get vaccinated. “If we can accelerate [the] rollout of vaccines, we’ll be in better shape by fall,” he says. It falls to the counties to implement the rollout locally, and all three have plans in place. However, those plans required some adaptations after U.S. Health and Human Services announced in January that it didn’t have a stockpile and couldn’t deliver the amount of vaccine anticipated.

When the vaccine arrives, the counties are ready to go into action. Tyler Evans, M.D., deputy public health officer and chief of the vaccine branch in Marin County, explains that trucks with the vaccine come directly from Pfizer and Moderna’s plants, and a war room in Washington, D.C. tracks them to make sure they go where they’re supposed to. The county’s point of distribution is the Marin Center in San Rafael.

“The minute we get it, we’re it turning around,” says Evans, reporting that the vaccines are administered the next day and through the week. The phases for vaccination are decided at a state level, and health equity is important.

According to Evans, occupation, age, medical history and home environment determine priority, and people should know their phases. Marin started vaccinating people in Phase 1a in December, and Evans expects the vaccine to be available to the general public by summer.

Challenges

By the end of January, the United States had logged more than 24 million cases of COVID-19, and more than 400,000 people had died. The country didn’t take sufficient effective measures to contain the virus at the outset, but Winslow points out that people didn’t realize how quickly it could spread. “Transmission was already established before we realized that a new disease was spreading quickly, and we were facing a pandemic,” he says. The politicization of a public health crisis also put the country at a disadvantage. Empowering a federal agency is important in a pandemic, he explains, and CDC would traditionally fill that role but was largely disempowered by the Trump Administration.

As a result, states and counties had to figure out what to do on their own. In addition, without clear federal guidelines, people were free to cross county and state lines. “That was a real recipe for disaster. We should have had a more centralized plan to control this pandemic,” he says, adding that the spread of misinformation and denial created serious problems. “Misinformation and disinformation have been very, very damaging in our country.”

Several countries contained the virus early, but the U.S. was slow in its response in some ways, partly because it failed to recognize the magnitude of the risk, but also because it’s a large, complex country. The borders with Canada and Mexico were closed to land travel in March last year by mutual agreement, but air travel was permitted much as usual. The U.S. government restricted air travel from China and countries in the Schengen Zone (nations in the European Union that don’t require passport checks) early on, but it didn’t put any COVID-19-related measures into place for travelers entering the country until January this year, when it began requiring proof of a negative COVID-19 test. Meanwhile, tens of thousands of passengers came into the country, including a substantial number from China early in the pandemic, and they could move about freely once they’d cleared customs.

In contrast, New Zealand put an order into effect on March 16, 2020, that required anyone arriving from another country to self-isolate for two weeks. A few days later, it also closed its borders to anyone who wasn’t a citizen or a resident. The measures were drastic, but by imposing them while the number of infections was still relatively low worldwide, the country flattened the curve and kept it there.

Bill Lindqvist, a Tiburon resident who is a New Zealand native, traveled to Auckland in November 2020, and other than having to wear a mask and physically distance, he did not have to fulfill any requirements to either leave the U.S. or return. Before he could board his outbound flight, he had to show proof of his quarantine plan. “I had to have a confirmed place in quarantine in New Zealand,” he says. He made arrangements ahead of time online, and on arrival, he picked up his baggage, cleared customs and then provided documentation showing he was accepted to quarantine.

Next, a special bus for passengers who must quarantine took him to a hotel that was cordoned off by high fences. He didn’t have a choice of hotel, but it exceeded his expectations. “As luck would have it, I was in the best quarantine hotel in the country. Other than being confined for two weeks, I couldn’t have asked for anything better,” he says. A nurse took his temperature, and he had to answer a questionnaire related to his health and then he got his room assignment, walked to the elevator by himself and found his room. He had a choice of meals, which were delivered to his room three times a day, and he could also order up to six bottles of beer or a bottle of wine each day. “The food was absolutely fantastic. The only complaint I had was that there was too much of it,” he says. The hotel included a large exercise space and an isolated parking area where guests could walk. “I used to go down for 45 minutes or so in the morning and also in the afternoon,” he says. “It was a real lifesaver.” The cost was about $2,200 U.S. for accommodation and meals for two weeks. When he returned to the United States on Dec. 23, “There was no testing of us in any way,” he says. He didn’t have to have his temperature taken or answer a single pandemic-related question.

In another approach, Denmark, which is notable for its clear messaging, acted quickly to provide a $6 billion economic help package. Negotiations took just 24 hours, and Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen announced the package on March 15, 2020. Among its provisions, it paid workers 75 percent of their salaries so they could stay home and helped small businesses cover their losses while the country was shut down. In June, Denmark also introduced a contact-tracing app similar to one California introduced in January 2021. Denmark is a small Scandinavian country with a high reserve of public finances and a political philosophy that allows high taxes, and New Zealand is a small island nation with the capacity to restrict travel more easily than would be possible in the United States. Despite the differences, however, both cases demonstrate that early action delivered results.

Strategies

Locally, shelter-in-place orders went into place in mid-March of last year at a time when Sonoma County had only a handful of cases. “That was really the most effective thing. That’s how we flattened the curve,” says Sundari Mase, M.D., Sonoma County public health officer. “We know a lot more about SARS CoV-2 than we did in the beginning, and as we’ve learned more, we’ve changed strategies,” she adds. Sonoma was one of the first counties that tested all contacts, both symptomatic and asymptomatic, and paired with contact tracing, the strategy has worked well, she reports, allowing the county to adjust the number of days people have to isolate or quarantine.

The current focus is on vaccinations. “We need to get as many people vaccinated as possible,” she says. “I do believe the priority scheme is a good overall framework,” she adds, explaining that it allows some flexibility, as do the state’s tiers for reopening. Sonoma began Phase 1 on Dec. 18, and the county’s role is collaboration and coordinating with health-care partners because Sonoma County has a large population and doesn’t have any direct patient-care clinics “We rely on our health-care partners to get the job done,” she says. She adds that paramedics, EMTs, dentists, retired physicians and nurses and other volunteers who are trained to give vaccines have stepped up to help. “I’m so impressed with our partners and how everyone has come together,” she says. “People are stepping out of the woodwork to help.”

Napa County also took early measures to manage the pandemic, and its Emergency Operations Center opened to provide a framework for planning ahead and communications. “It is the same process we use for mitigating large wildfires and earthquakes, and it’s been useful as an overarching approach to deal with the challenges of this pandemic as well,” says Karen Relucio, M.D., the county’s public health officer. Early measures to stop the spread were effective, she adds, but Napa experienced a surge after Thanksgiving as a result of pandemic fatigue and people who couldn’t resist traditional holiday gatherings and travel, a reflection of what happened throughout the country. “We’re facing many of the same challenges other counties are,” she says, but she feels fortunate to have the support of local health-care partners and volunteers to overcome them.

With the massive surge waning and vaccines available, there is reason to hope for better days ahead. Meanwhile, everyone must still follow the protocol to help reduce the spread: wear a mask, practice physical distancing and thorough handwashing and stay home as much as possible, leaving only for essential activities. The guidelines also apply to people who have been vaccinated. A number of them still have a chance of contracting the virus, and they could infect others, especially if they’re asymptomatic. Mase adds patience to the list of good practices. She understands that people are having difficulty staying home for so long, but they need to be patient and wait their turn for the vaccine. “It will come,” she says. And once enough people have bared their arms, been inoculated and allowed time for herd immunity to develop, we can gain the upper hand over SARS CoV-2 and reclaim a normal life.