For local muckraker and affordable housing advocate, Dave Ransom, his crusade for access to equitable housing in the North Bay began a decade ago. A third of the men in his church men’s group experienced foreclosure. This immediate rash of foreclosures spurred Ransom to join the fight and help form the Sonoma Valley Housing Group. It’s a fight that he and many other housing advocates and organizations have waged with a continually dwindling lifeline of dire resources for low- to moderate-income level residents.

Ransom, who compiles a roundup of local news and politics in a weekly newsletter distributed via email for subscribers interested in learning more about city and county actions, says affordable housing in the North Bay can’t be created without government subsidies and the passage of rent control. “The strategy of the local powers that be at this point is to build, build, build, as opposed to rent-control,” he says.“The idea is if there are enough houses, the rent will drop. I think local officials are trying to get around the lack of affordable housing by building more higher-income housing.”

“We’re all workforce; the workforce is everyone but the 1 percent. We need to talk about it as housing for all of us essentially.”—Dave Ransom, community advocate, Sonoma Valley Housing Group

In 2017, a rent-control ordinance for Santa Rosa was on the ballot in the form of Measure C. If passed, the ordinance would have established a 3-percent cap on annual rent increases and eviction restrictions. The measure was narrowly defeated, ironically, by a less than 3-percent margin. Cut to more than three years later and Sonoma County renters accumulated a $36.5 million rental debt, according to bayareaequityatlas.org. The debt can be attributed to the pandemic’s crippling effect on the formerly booming service industry in the area, one of the primary employment sectors in the North Bay.

“Workforce housing is a problematic phrase,” Ransom says. “We’re all workforce; the workforce is everyone but the 1 percent. We need to talk about it as housing for all of us essentially.”

A New Workforce

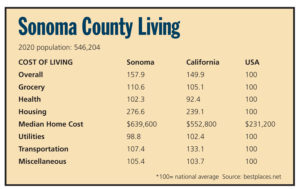

COVID-19 has wreaked havoc on nearly every facet of life, including the housing market, specifically in the Bay Area. As the virus continues to ravage the nation, denizens of densely- populated cities seek refuge in greener pastures known as the suburbs. The Bay Area experienced a seismic shift in population, seeing unprecedented levels of vacancy rates and a more than a 35-percent drop in rental prices. Initially, it was suspected that those partaking in what has come to be known as the “tech-exodus” were hitching their wagons out of the state for places such as Arizona, Colorado, and Texas. However, new data released by the United States Postal Service shows that most Bay Area residents are remaining within the region, with Sonoma County as the sixth, most popular destination.

The recent influx somewhat offsets the consistent outflow of population loss in Sonoma County, which has lost around 3 percent of its residents annually since the 2017 wildfires. The uptick in “remote workers” in the area has further diminished an already dwindling supply of housing and contributed to a soaring real estate market. According to the North Bay and California Association of Realtors, Sonoma County’s median home price of $720,000 went up by $5,000 between November and December, an 8-percent increase from 2020 to 2019.

Keith Becker, general manager of DeDe’s Rentals in Santa Rosa understands the appeal of Sonoma County. When you compare Sonoma County to surrounding counties, he says, Sonoma County is not as highly populated or developed. “The other counties in the East and South Bay are heavily congested, which makes Sonoma County draw a certain type of interest for remote workers.”

Becker says the area needs to provide an equal balance between supply and demand, allowing for enough affordable housing for those who want to live and rent in the county. “There has never been enough inventory to fit the need. The average median income for a family of four is about $100,000, and if all you build is Fountaingrove-style houses, you’re not serving the needs of the community. And everything that goes into the construction of new homes is so costly that you can’t build inexpensive housing and sell it affordably without taking a loss,” he says.

The young-tech professional is an attractive demographic for a county that has predominantly been home to an aging population. According to a 2016 report from the Sonoma County Department of Health services, about one in five residents was age 65 and older. Becker sees the need for new life injected into the community, but is cautiously optimistic at what that means for the current makeup of the area.

“If you want Sonoma County to be younger, how do you make it affordable for younger people to invest and own here? To fill out the infrastructure? To be the next generation of business owners and housing providers? We do have young people on our city council, but they can’t be the exception to the rule,” he says.

“The average median income for a family of four is over $100,000, and if all you build is Fountaingrove-style houses, you’re not serving the needs of the community.”— Keith Becker, general manager, DeDe’s Rentals

A shift Becker has noticed in the local real estate market is the increasingly difficult pathway to homeownership for first-time buyers. He says the small, mom-and-pop landlords in the area are being replaced by a new generation of owners who may not or cannot offer single-family properties at affordable rates for local tenants. “Will there be a place in Sonoma County where the next generation can see themselves?” He asks.

Breaking Ground

The challenges of building housing in the North Bay are numerous, even more so at an affordable rate. The scarcity of zoned-land, the cost of supplies and labor, and an extensive and lengthy permitting process place many developments on hold. Mike Gasparini, co-owner of the Paseo Vista project in Sonoma is quite familiar with the hurdles home builders face.

“The project got approvals with Sonoma County for 167 units in 2012, we didn’t start construction until late 2017. We were within a joint, county-city jurisdiction, so whatever we got approved at the county had to also be approved at the city,” he says.

The Paseo Vista development is currently selling single-family homes in Southwest Santa Rosa starting in the mid-$400,000 range. Gasparini says they use the term “affordable” because their current price point is the lowest-priced new homes for sale in the county. The project is a third of the way to completion, and Gasparini says the project should be finished by the end of next year. Although the approval process for development is challenging, Gasparini says the city has worked to expedite the permitting process to make it easier for future projects to get off the ground.

Another obstacle to the creation of affordable housing in the area is the limited supply of land to build on. “The Santa Rosa city boundaries are frozen, as well as most cities in Sonoma County, which makes the supply-and-demand cost of housing high,” says Carlson. With limited land, there are limited options to accommodate low-income renters or buyers. The county is looking at the Sonoma Developmental Center in Eldridge as a possible site for housing a low-income community, but Carlson feels the site is not the answer. “It’s an area where you need transportation; you’re cut off from most goods and services. It’s like they want to keep certain people out of sight,” he says. Carlson feels sites such as the Sonoma Developmental Center, are examples of “the haves,” segregating low-income communities from a socioeconomic standpoint by disconnecting them from the main arteries of the city and county.

“There used to be a community design of duplexes on corner lots within R1 districts,” he says. “They were rentals, but also could be set up for each half to be purchased. In the ’50s and ’60s, the government built mass housing for the low-income [families], and today they are known as ghettos. Let’s not repeat history.”

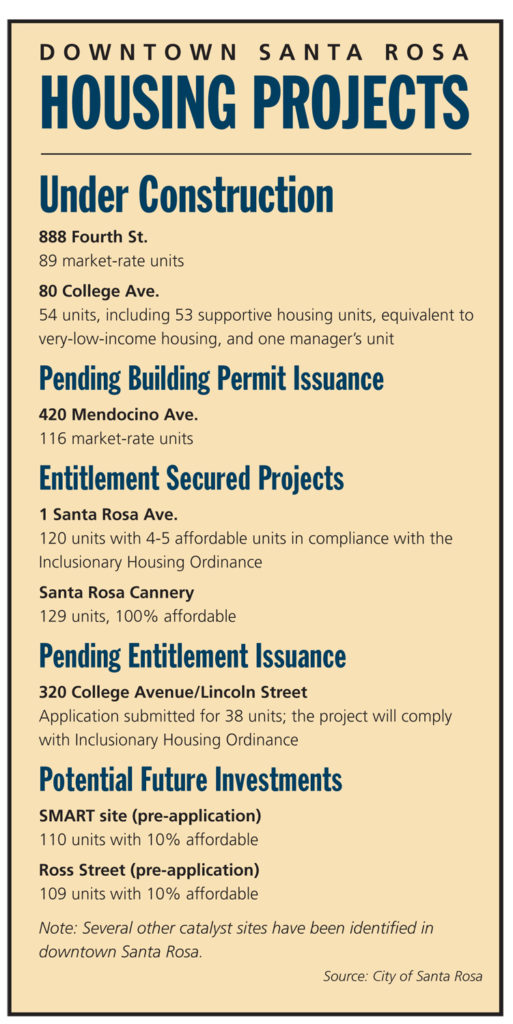

An area that has experienced an uptick in development and interest: Santa Rosa’s downtown core. The current and future projects underway could lead to more than 800 units in the area, with less than 250 of those units projected as affordable or low-income housing. The city has long desired a viable downtown, something it’s growing increasingly desperate for in the wake of pandemic-afflicted brick-and-mortars in the area. The city hopes that the construction of increased housing will revitalize the languishing downtown. Officials worked to streamline the development in the area with reduced fees and incentives included in the High-Density Multifamily Residential Incentive Program.

However, Carlson notes the potential issues with living in the area. “There’s no grocery store or any substantial place to walk to for goods to sustain the household. Those people who would live downtown are going to need cars to go to the grocery store, and where are they going to park their cars downtown?” he says. “What happened to planning for a green city?”

Keith Woods, CEO of North Coast Builders Exchange, an 1,100-member contractors association, says the issue of parking can be resolved with underutilized garages in the area. He also believes that with enough housing built, the downtown market could attract a serviceable grocery store.

“Malls will have to get creative in the future with their space. There is a model for a grocery store going into those large retail spaces right here with the Coddingtown Whole Foods,” Woods says. “The demand is there from Kaiser, Medtronic and the tech workers coming from the Bay Area seeking quality, high-end housing.”

Woods says Sonoma County’s housing problem has become a housing crisis. “When you talk about affordable housing, the estimates are we are close to 30,000 units short of what we need to accommodate our existing population and any future growth.”

To stimulate future growth of the community, Larry Florin, CEO of Burbank Housing, a Santa Rosa-based nonprofit dedicated to building quality affordable housing in the North Bay says the organization currently has eight projects in development. The 3757 Mendocino Avenue housing project, located at the former Journey’s End Mobile Home Park site, is the most expansive among them, a 532-unit development on more than 10 acres of land. Burbank housing worked with Related California, a Los Angeles-based for-profit developer, to acquire $40 million in tax credits to help with the cost of initial construction.

“We build with prevailing wage. The skilled and trained workforce’ limits your contracting pool and drives up costs because the pool of bidders on a contract is dramatically reduced and contractors will not bid on a ‘Skilled and Trained Workforce’ job because they can’t hire their own staff for the project. The building trades are pushing this on every piece of legislation coming out of Sacramento.” — Larry Florin, CEO of Burbank Housing

Florin says the key to creating affordable housing in the North Bay is with some form of public subsidies, and that can be tricky as the rules for subsidies and use continually change. He says the state of California has “gotten back in the business of housing” recently by providing $5 billion in funding to the multifamily housing program. The increase in state funding is crucial, but Florin says more needs to happen on a local level.

“Affordable housing funding has never happened in the North Bay by way of a ballot measure. We have to use local subsidies to leverage tax credits in local funding. This past November, Measure O passed as an initiative to fund mental health, addiction, and homeless services; there’s a will for the electorate to spend money when it’s done right. We have to overcome the push-back on housing funding for future measures,” he says.

Along with a lack of support for housing measures, Florin says development is hampered by the “skilled and trained workforce” requirements imposed by the state.

“Construction cost continues to skyrocket, 80 percent is labor cost. Every time you impose a new set of requirements, you dramatically increase your cost; 90 percent of what Burbank Housing builds, we build with prevailing wage. The skilled and trained workforce’ limits your contracting pool and drives up costs because the pool of bidders on a contract is dramatically reduced and contractors will not bid on a ‘Skilled and Trained Workforce’ job because they can’t hire their own staff for the project. The building trades are pushing this on every piece of legislation coming out of Sacramento,” he says.

“Skilled and trained workforce requirements” state that contractors have at least 30 percent of journeypersons be graduates of an apprenticeship program in a variety of fields. For contractors unable to comply with the mandates, the state labor commissioner can assess penalties of up to $5,000 per month for work performed in violation of this chapter. For a second or subsequent violation within a three-year period: $10,000 per month for work performed. When violations are considered “willful” or “with intent to defraud” the penalty assessed by the labor commissioner can include debarment. Subsidies and skilled and trained workforce requirements aside, the lack of accessible land is a major factor in the open spaces of the North Bay.

“How do you access land in a place where they value open space and a certain quality of life?” Florin says. “And you can’t keep up with the demand, causing people to spend more of their income on housing to keep up. North Bay residents spending more than 50 percent of their income on rent is normal here.”

Florin believes allowing multifamily housing to be built in traditionally single-family residential neighborhoods is a step in the right direction in a place with a growing population and limited land. “Our infrastructure is depleted,” he says. “I do think there is one very tangible [option]: rezone residential neighborhoods to allow multifamily homes. Ironically enough, Berkeley is looking at doing that now, and that’s the place where exclusionary zoning started.”