The United States has more immigrants than any other place in the world. In fact, more than 40 million people living in the U.S. were born in another country. That population is diverse with almost every country represented. According to a recent Pew Research Study, approximately two-thirds of Americans say immigrants strengthen the country with their hard work and their talents. Yet over the past few years, portions of that population have been subjected to discrimination and racial prejudice—Asian Americans in particular.

Sonoma County is indebted to its Asian American immigrants. The county’s agricultural roots can be traced back to their arrival in the late 1800s. Their skills in farming, grape growing, pruning and winemaking led to the modern-day wine industry. And they continue to contribute to the local economy and community in many ways. Here are their stories, past and present.

Akiko Freeman

Winemaker

“I owe my interest in wine to my grandfather,” says Tokyo-born Akiko Freeman, winemaker at Sebastopol’s Freeman Vineyards & Winery. “At 27, he was the youngest economics professor at Tokyo University,” she says. “He studied in the UK and while there became acquainted with the wines of Bordeaux. My father preferred Burgundy. There was always wine at our dinner table. I’d listen to discussions about the color, bouquet and the taste.”

Akiko attended Manhattanville College in Purchase, New York, to learn English. There, she met Ken Freeman at a Hurricane Gloria sheltering party. Ken, crewing on a boat off the coast, had been diverted to shore. The couple discovered a shared love of good food and good wine. Akiko went on to get her master’s degree in Italian Renaissance art at Stanford. Following a stint in Asia, the Freemans returned to San Francisco, setting their sights on the Sonoma Coast and the dream of starting a winery. After years of searching, they acquired a 14-acre former apple orchard in Sebastopol and planted Pinot Noir grapes. The vineyard is named Gloria, a nod to the hurricane that brought them together. In 2007 the Freemans acquired a 52-acre former sheep ranch closer to the coast. The property has spectacular stands of primary and secondary growth redwood. They gifted 22-acres to the Bodega Land Trust. An existing 14-acre clearing was planted with Pinot Noir and Chardonnay grapes. That vineyard is named “Yu-ki” meaning big tree. It’s also the name of Akiko’s nephew.

Akiko began a 10-year winemaking apprenticeship under the tutelage of Ed Kurtzman, the former winemaker at Bernardus, Chalone and Testarossa. “I asked many questions,” Akiko says. “Ed was so patient. He was the perfect mentor.”

One of Freeman Winery’s most popular wines is Akiko’s Cuvée. “Each year we have a blind competition for best blend. Everyone at the winery, including Ken and Ed, participate. I’ve won for the last 18 years. I hope I keep winning as otherwise, we might have to change the name of the cuvée,” Akiko says with a laugh. “We are fortunate to have vineyards near the coast. The cooler weather allows the grapes to mature longer on the vine. That provides for natural acidity and more elegance, more wine complexity,” Akiko says.

Their Chardonnay “Ryo-fy” means a cool breeze. It was served at the White House in 2015 at a state dinner honoring Prime Minister Shinzō Abe, and it was the first occasion that wine made by a Japanese winemaker was offered at a White House event.

“I enjoy the process of winemaking. I love the smell of the fermentation and macerating the grapes,” Akiko says. “Prior to the harvest, I spend a lot of time in the vineyard sampling the fruit. One day the grapes suddenly have umami, that wonderful special flavor. I want to eat them all. Then I know it’s time to harvest.”

Freeman Winery produces approximately 5,000 cases a year. Ten percent goes to Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore and the UK. The winery is open daily, with reservations required to visit. For more information, visit freemanwinery.com.

Aaron Lee,

Distiller

“I’m second-generation Asian American,” says Aaron Lee, partner at Barber Lee Spirits. “My parents grew up in Hong Kong. They came to the U.S. for opportunities and better education. They met in college. Both now manage small businesses in San Francisco. I inherited my entrepreneurial interest from them.”

Lee became acquainted with Michael and Lorraine Barber through their Barber Cellars wine. Inspired by the California rye renaissance, the couple decided to also try their hand at making spirits. While most rye whiskey on the market originates from the barrel stocks of Kentucky, Indiana and Canadian distillers, California distillers make theirs from scratch using their own grain mash recipe, distilling and aging the product themselves. The Barber’s first rye production, aged for two-and-a-half years, was released in 2016. It sold out within weeks. Fortunately, Lee got to taste it. He was eager to get involved in a startup business with potential and the Barbers needed a partner to expand. Barber Lee Spirits opened its doors in 2019. Currently, the distillery produces five spirits—single malt rye, heirloom corn bourbon, apple brandy, rum and moonshine. “Rye and bourbon are the most popular,” Lee says.

Barber Lee makes 3,000 gallons a year, and each batch is made from scratch. To be recognized as single malt, the whiskey must be made by a single distillery from a single malted grain. “It’s very difficult to make,” Lee says. “The malted rye turns thick and sticky during mashing. That’s why many distillers shy from using malted rye in higher proportions. And that’s why you don’t see a lot on the market. For us, it’s well worth the effort. Our rye is rich, spicy and unique.”

Unique also describes Barber Lee’s Heirloom Corn Bourbon. “Today, 99% of all corn grown in the U.S. is yellow dent #2 and most bourbon is made from that variety,” Lee says. “Yet the old varieties provide more protein and have a unique character. It’s like different grape varietals used in winemaking. Different corn species impart different flavors to the bourbon.” As a result, there’s been a resurgence of old corn species among small farmers. Barber Lee’s bourbon is made from non-GMO Bloody Butcher and Hopi Blue corn grown in California’s Central Valley. “The Bloody Butcher adds spicy flavors of buckwheat, chili peppers and cherry,” Lee says. “The Hopi Blue provides a rich and earthy taste.” The bourbon is aged in new, heavy char American oak barrels. The first batch of Heirloom Corn Bourbon sold out in only four months.

Another unique spirit available is Absinthe. “Absinthe is an acquired taste—either you like it or you don’t,” says Lee. “Our Absinthe Blanche is less driven by anise and more botanical. There are so many herbs and spices available in California. We settled on eight that provide a delicate, sweet, floral expression.”

The distiller’s product uniqueness extends to the labels on the bottles. With the exception of the Apple Brandy, the labels are recycled etched leather. The brandy label is wood from an old apple tree.

Barber Lee Spirits are located in downtown Petaluma in a 1910 warehouse. “We are very much about community,” Lee says. “The town of Petaluma has been terrific in supporting us.” Tasting room décor is a combination of rustic farm combined and modern industrial. There are old brick, barrels and leather chairs. The mural on the back wall is an amalgamation of the products and the area—grain and corn for whiskey, a double-headed snake for the distillery’s double-headed still, wormwood for absinthe, the Golden Gate Bridge and a Petaluma chicken. It’s by local artist Maxfield Bala. Visitors can enjoy a cocktail from a menu of 21 selections or just taste the spirits. “Club members get a 50% discount on cocktails. For them it’s like Happy Hour all the time,” Lee says. The distillery is open Thursday through Sunday. For more information, visit barberleespirits.com.

Erin Wilkins

Traditional Japanese-Chinese Medicine Practitioner

“We’re fortunate,” Wilkins says. “Many of the herbs that I use at the shop grow in abundance in Sonoma County. All are pesticide-free or organic. Whenever possible we source sustainable herbs grown by local small independent farmers.” Herb Folk offers a range of products: herbal and green teas; California-grown single herbs and herbal formulas; tinctures; powders; seaweeds; bath and body items; and topicals. All products are available online at herbfolkshop.com.

“Our green tea, Mas Gen Mai Cha, is blended with roasted rice. It’s named for my grandmother,” Wilkins says. “She’s been drinking green tea for most of her life. At 96 years old, she’s still going strong.” Green tea was brought to Japan from China in the 9th century. Now it’s an essential part of the Japanese culture, often served as a symbol of hospitality. In the 1920s, Michiyo Tsujimura, biochemist and Japan’s first woman Minister of Agriculture, discovered that green tea contained significant amounts of vitamin C and catechins or flavonoids with anti-inflammatory and cancer-fighting properties.

“Our broth herbs impart healing energetics to broth, soups and various recipes,” Wilkins says. “Or, they can be made as a tea and added to smoothies, oatmeal, or other cereals. Our Qi broth provides energy and mental clarity. While the Yin broth is for restorative purposes, anxiety and insomnia.” Herb Folk’s sustainably harvested seaweeds are sourced through Santa Rosa’s Strong Arm Farms. “Seaweed is rich in minerals and trace elements. It’s the perfect additive for soups or salads,” Wilkins says. Herb Folk provides acupuncture by appointment. “Acupuncture can be combined with cupping where cups are placed on the skin to create a vacuum,” Wilkins says. “This increases blood flow that can relieve muscle tension and reduce pain.” Olympian Michael Phelps and other swimmers, gymnasts and athletes have popularized cupping.

The National Center for Health Statistics reports that more than 30% of Americans have used alternative health care. Most major health care providers now offer integrative medicine with doctors embracing evidence-based alternative therapies combined with mainstream treatment.

Kanaye Nagasawa

Paradise Ridge

Kanaye Nagasawa grape grower, winemaker and owner of the former Fountaingrove Winery in Santa Rosa was dubbed the “Grape King of California.” That accolade came via a circuitous route. In 1865 at age 13, he and 14 others of samurai heritage were smuggled out of Japan and sent to the UK to study and become acquainted with the ways of the west. There Nagasawa met an American, Thomas Lake Harris, who grew grapes on a farm in New York and dreamed of a Utopia in California. Harris acquired acreage in Sonoma County he called Fountaingrove Ranch. When Harris returned to the East Coast he left the operation in Nagasawa’s good hands. Nagasawa planted 375 acres of grapes on the 1,800-acre spread and was the first to ship California wines to Europe. In 1924, the Emperor awarded Nagasawa the Order of the Rising Sun presented to those who contribute to international relations, promote the Japanese culture and make significant achievements in their field.

“In its day, Fountaingrove Winery was producing a third of all the wine in Sonoma County,” says Rene Byck, co-owner of Paradise Ridge located a half-mile from the Fountaingrove site. Paradise Ridge’s tasting room displays vintage photographs dedicated to the legacy of Fountaingrove and Nagasawa. His samurai sword, salvaged from the rubble of the Tubbs fire that decimated Paradise Ridge, occupies a place of prominence in the rebuilt facility. And a vineyard with Chardonnay grapes is named for Nagasawa. “In 2018, Chardonnay from the Nagasawa Vineyard was served at the 150th year commemoration of the restoration of the Meiji and the establishment of Japan as a nation-state,” says Byck.

Jack Ding

Unicom Tax Services

Sonoma’s Jack Ding got caught up in China’s Cultural Revolution. Ding grew up in Changzhou, China, on the Yangtze River outside Shanghai. “My father was a surgeon, my mother a nurse,” he says. “We were forced to move to the countryside. Unlike studying at normal schools, students needed to learn from workers and peasants. Students took a lot of time to learn how to farm and operate tractors and pumps. I still have scars on my hand from using a sickle to harvest rice.

“I was a teenager then,” he continues. “I missed important years of my academic education.” As China emerged onto the world stage, its leaders shifted focus to manufacturing and technology. Yet the lost generation lacked the skills to implement the new plan.

“The government set up a Workers College to teach all the subjects I’d missed, and then, teach calculus and advanced physics,” Dings says. “And they formed a joint education program with Western colleges and universities.” With selection and examination, Ding was accepted into that program. Then the Tiananmen Square event brought the program to an end. Dominican University, a participant in the program, realized the importance of maintaining long-term Pacific Basin/U.S. relations. The college offered scholarships to worthy Chinese students. Ding applied and got accepted. “Dominican University changed my life,” he says.

After graduating with an MBA in 1995, Ding took a job with a semiconductor company in Fremont. Though his job was in marketing and sales, he became fascinated with the U.S. tax code. “It was complex and no one could get my answers to questions. So I began to study and learn more.” His fascination led to a new career. He passed the arduous test required to become an Enrolled Agent (EA). EA’s are the only federally-licensed tax practitioners who specialize in taxation and are allowed to represent taxpayers before the IRS. Initially, Ding worked with a Sonoma CPA firm prior to setting up his own practice, Unicom Tax Services. “Most of my business is tax consultation, helping people solve complicated tax issues,” Ding says.

In 2020, Ding became the first Asian American elected to the Sonoma City Council. He is also the town’s vice mayor. For those who know Ding, his election was not surprising. He’s long been active in civic affairs, including Sonoma Overnight Support, Sonoma Valley Citizens Advisory Commission and other nonprofit organizations.

Ding observes that the contribution of Chinese laborers to Sonoma Valley’s wine industry has largely gone unnoticed. “I went to a bookstore and bought a book on Sonoma history. There were no photos and little mention of the Chinese,” Ding says. He and the Sonoma Sister Cities Association, along with the Penglai Committee proposed the building of a ting, a tile-roofed pavilion to honor Sonoma’s unnamed Chinese. The city council unanimously approved construction in a city park. Fundraising for the project continues.

“Being a first-generation immigrant, I understand both challenges and contributions,” Ding says. “I came to this country to live the American dream. The best way to realize that dream is to contribute to the community and participate in the democratic process.”

Thriving on diversity

Beginning as far back as the late 1800s, Asian Americans, through their hard work and talents, have made significant contributions to the economy and community. And that continues today. Sonoma County thrives on its diversity. As Winston Churchill once said, “Diversity is the one true thing we all have in common…celebrate it every day.”

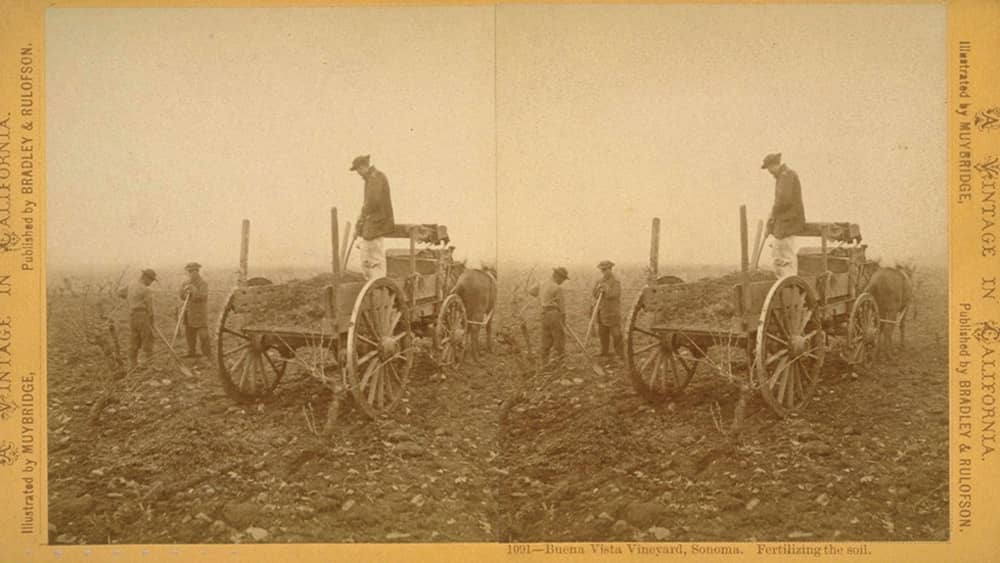

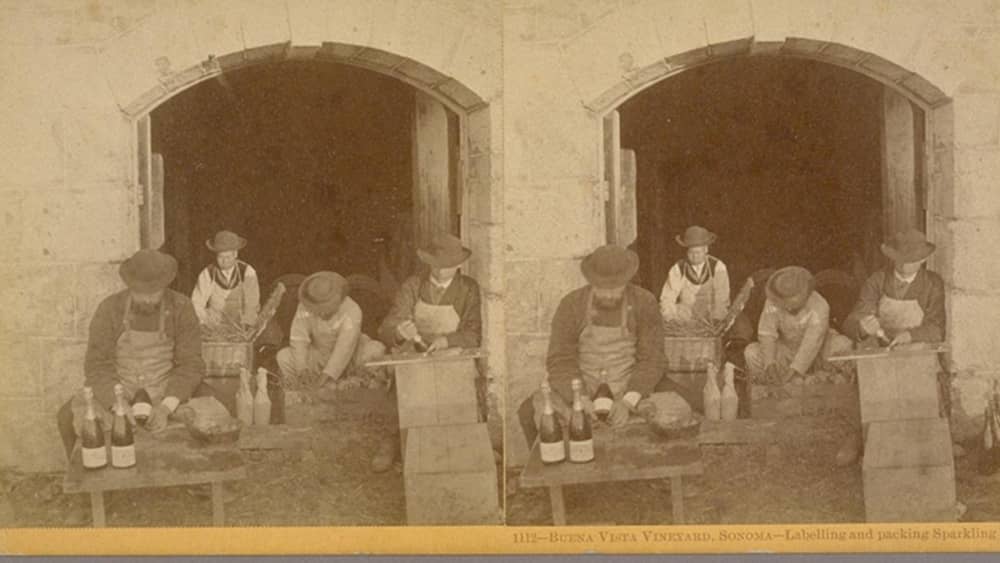

Buena Vista Winery

As the transcontinental railroad neared completion and the Gold Rush fizzled, Chinese immigrants searched for work. Count Agoston Harzathy, an immigrant from Hungary, hired 150 Chinese laborers to come to Buena Vista, the winery he founded in 1857.

On the path leading to Buena Vista visitors are greeted with signage highlighting the winery’s history. One of those signs pays homage to the early Chinese. It reads: “We at Buena Vista are proud of our Count’s support of California’s Chinese immigrants. Without their invaluable assistance, Buena Vista would not have become the first great American wine estate…”

Tom Blackwood, the general manager, says, “They cleared roads, dug wine storage caves out of bedrock and performed highly skilled agriculture. The Chinese were involved in the entire winemaking process from de-stemming and crushing, fermentation, racking, individually filling and corking bottles and wiring the sparkling wine cages.” They also erected two stone buildings at Buena Vista to accommodate a crusher, fermenting tanks and barrels. This was revolutionary at that time when other wineries still resorted to manually stomping the grapes with their feet.

In his book, The Beast of the Field, Richard Steven Street writes: “…between 1856 and 1869, Chinese planted the majority of the county’s 3.2 million grapevines allowing Sonoma to increase production from a few hundred gallons to nearly three hundred thousand. Street goes on to highlight the role played by the Chinese in improving wine quality by ripping out the old mission grape vineyards and replanting them with …Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay and other fine French and European varieties.

When threatened for hiring Chinese labor, legend has it that Hararzthy carried a revolver to protect them, and himself.