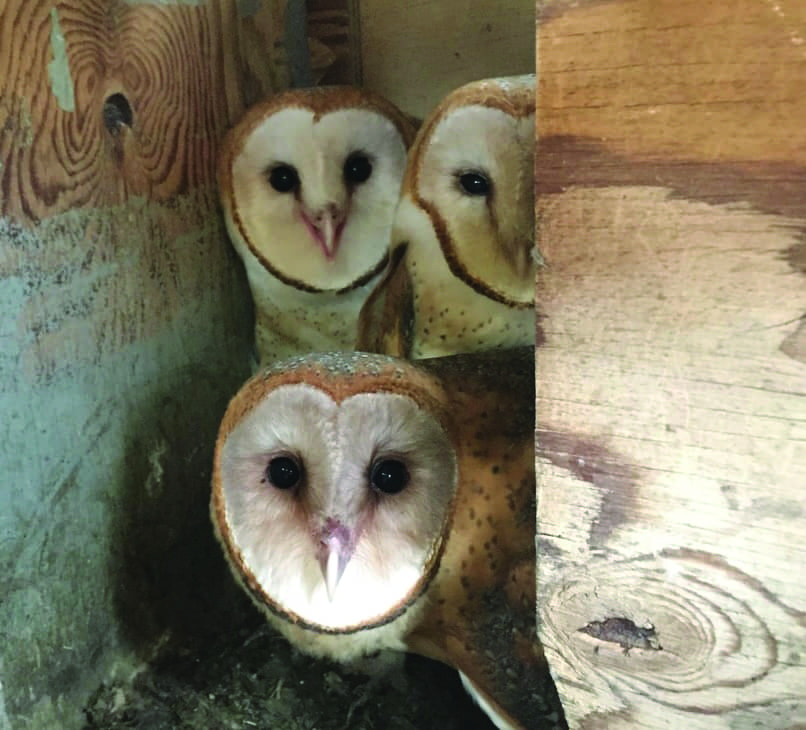

Image of common barn owl while feeding on a wooden hemp on against a dark background

In 2011, Sonoma County Wildlife Rescue (SCWR) was on the brink of closing its doors. “We were operating on a very small budget, with barely enough money to feed our animals,” says Doris Duncan, executive director. But everything changed with one phone call.

Greg the Gopher Guy, who operates his business from Santa Rosa, was known for trapping gophers at various wineries, and Duncan asked if her team could come take the trapped gophers off his hands for feed. While visiting the winery site, the team noticed barn owl boxes and asked if they could look inside to see if the boxes were occupied. They had an unusually large number of orphaned barn owls at the rescue and wanted to foster them into an active nesting box so the parent owls would care for them. “Luckily, barn owls can’t count,” says Duncan, “all they know is that there’s another mouth to feed.”

That was when they discovered that people weren’t cleaning their owl boxes. According to Duncan, each nesting period, one-third of the owl box will fill up with feces and pellets from the young owlets. “If an owl box never gets cleaned, it will fill all the way to the top,” says Duncan. She adds, the mother owl doesn’t know any better—owls are cavity nesters and will simply find an empty cavity to occupy and raise their young. This can have deadly consequences. If there is not enough room to house all the owlets, they will push one another out of the nest onto the ground, where they will starve or be eaten by a predator.

Duncan and her team began researching and collecting data about the poor conditions of the boxes and how the barn owls were affected. Not only were the boxes not getting cleaned, many of them were built too small or with inferior materials and poor placement, which led to significant injuries or death. “We realized that we could put together a whole program. It would be so much more than just cleaning boxes,” she says.

Maintaining owl boxes

“The Barn Owl Maintenance Program [BOMP] has three functions,” says Kelsey James, volunteer and community support coordinator. “One is installing barn owl boxes, the next is monitoring—when we go out in the spring to check occupancy, and in the fall, we do maintenance.” According to James, maintenance is the most critical part of box ownership. “Barn owls take about 60 days to fledge from a box and leave on their own from when they’re hatched.” It’s critical to do maintenance once the barn owls have left the nest because the box is filled with waste and needs to be prepared for the next nesting season.

BOMP’s owl boxes are designed to best meet the needs of barn owls and protect against predators. The boxes are made to handle extreme weather, with ample shade and wind protection. They are mounted on galvanized steel poles so that raccoons and other predators cannot climb up. The outside features grooves so that the parent owls can easily move in and out of the nest when feeding their young the rodents they catch and kill nearby. There is also a maintenance flap to make the boxes easier to clean out.

Sustainable pest control

“The need for barn owl boxes is so great, we are hardly able to keep up with the supply and demand some of the time,” says Duncan. In Sonoma County, many wineries and farms are working towards becoming certified organic, meaning that they must use natural and sustainable pest-control methods. She adds that people are also becoming more aware of the causes of global warming and want to make better choices.

Pesticides used to eliminate rodents—or rodenticides—are a common tool for eradicating pests in vineyards and on farms, but this has a detrimental impact on the environment. Rodents consuming these poisons typically do not die until several days after feeding. As the rodents’ health deteriorates, they become weak and slow, making them a target for predators. When owls and other wildlife eat the rodents, they become poisoned as well and will eventually die. During baby season, raptors could also catch these poisoned rodents and feed them to their babies, unknowingly killing them with the poisoned food. With fewer predators to control the rodent population, it becomes an endless and damaging cycle.

In its first few years of business, the Barn Owl Maintenance Program generated $90,000 in revenue and is now up to $120,000. “It brings in funding that we wouldn’t normally be receiving from the community,” says Duncan, adding that the community only funds 10% to 20% of SCWR’s budget. “When we create businesses like this in our community that help animals, people and us, it’s a win-win idea, and we’ve started helping other wildlife programs to start their own programs like this that bring in much-needed funding.”

Supporting the owl population

What kind of impact can this program have on the environment? The answer is simple: more owls. E&J Gallo Winery, one of the program’s first clients, started out with three owl boxes on one of their vineyards, and now they are up to 13, as the owls continue to nest there. “Since the owls have recognized the boxes as their home, a lot of owls have stayed in that vineyard,” says Duncan. This demonstrates that the owl population can actually be managed and populated. “That is something the owls have taught us,” she says with a smile.

For more information, visit bompco.org.

Owl Terms

Fledge is the stage in a young bird’s life when the feathers and wing muscles are sufficiently developed for flight.

Pellets are made up of the parts of an owl’s meal that they are unable to digest. After swallowing a mouse or rat, the bones, fur and whatever else cannot be digested is packed into a pellet, which the owl then spits up. Owls generally cast about two pellets a day.

Owlets are young baby owls, typically recently hatched, that rely on their parents for feeding, care and security.

Raptors are birds of prey that capture live prey. The name is derived from the Latin word “rapere,” which means “to seize.”

Author

-

Summer Young moved to Sonoma County in 2018 to attend college and fell in love with the area. She's passionate about promoting all that the region has to offer through her work in local business marketing and journalism. When she's not writing, she can be found drinking coffee and exploring new places with her husband.

View all posts