As national insurers look to limit or end California property insurance policies, North Bay homeowners and agriculture business operators are developing strategies to keep properties covered. Ideas include buying fire insurance from the California Fair Access to Insurance Requirements (FAIR) Plan and a difference in condition (DIC) policy for other risks, raising deductibles and choosing which personal property not to cover.

Insurers are leaving little room for negotiation.

Even renters and property owners in urban downtowns are seeing rate hikes. Insurers have recognized that there are also significant fire risks for structures in metro areas, especially for buildings on earthquake fault lines.

Home and ag business owners have been blindsided by the increases.

Many customers in rural areas have seen their rates double or triple or their policies not be renewed.

Joel Alexander, owner of Argos Insurance in Santa Rosa, says customers are questioning why they are seeing an increase now.

“The North Bay hasn’t had a major fire for several years,” Alexander says. “Yet the industry wanted to make changes years ago. The California Department of Insurance (CDI) is just now catching up, due to delays from COVID.”

Alexander says customers should hold off on modifying properties before learning their new rates.

“You could easily spend $30,000 cutting down trees, clearing brush and hardening structures and then face cancellation or a large increase,” says Alexander.

Property owners who are seeing non-renewals may not get clear answers as to why. Sometimes there appears to be logic to an insurer’s reasoning, like a fire affected neighboring homes. Other times insurers appear to be unfamiliar with local geography and microclimates.

“More-metro areas like downtown Santa Rosa and Petaluma could see a retention of reasonable rates and coverage. Yet even homeowners well within city limits are being non-renewed for wildfire exposure,” says Elissa Wadleigh, an insurance agent for Sonoma Valley Insurance Agency in Santa Rosa.

Some of the changes for ag businesses seem to be based on ZIP code. Wineries and growers with storage facilities in American Canyon are seeing non-renewals, says Ryan Klobas, chief executive officer of the Napa County Farm Bureau.

“There’s minimal fire risk there. So our members are struggling to figure out how they can get covered,” says Klobas.

Strategies to cope with changes

The first step to addressing concerns is to talk to an experienced insurance agent. With the market in flux, a property owner should speak to an independent agent who can

communicate with different insurers. The agent should know whether insurers are writing policies for the property owner’s area. Often the FAIR Plan is the only option.

“The FAIR Plan is the carrier of last resort. Their policies only provide a minimum of coverage,” says Peter Oser, president of Anixter & Oser, Inc., a Novato-based insurance agency.

Oser, whose family has been in the insurance business for four generations, says he has never seen the industry so volatile. He advises all policyholders to consider a high deductible. This may considerably lower their policy premium. High deductibles are $2,500 and up.

A property owner at risk of nonrenewal should avoid submitting minor claims. Property insurance claims are different from health insurance claims. The professional who repairs the damage will not send a report to the insurer. A property with two or more claims is likely to be non-renewed.

Methods to protect property

Cal Fire and University of California Cooperative Extension (UCCE) county offices are encouraging property owners to make modifications by focusing on the concept of defensible space. This is the 100-foot buffer, or fuel reduction zone, that should exist between a structure and a surrounding area. Homeowners create defensible space by removing combustible materials like dead and dying vegetation. They should start at the structure and work out away from it to create defensible space.

Cal Fire is currently accepting defensible space inspection requests for rural homes in state responsibility areas (SRAs), except in Marin County. In Marin County, rural residents should reach out to Marin Defensible Space . County UCCE offices advise ag business owners on how to create defensible space for ranches, farms, vineyards and wineries. A property owner in a city or a rural area that is not an SRA should contact their local fire department.

Tori Norville, the UCCE fire advisor for Marin, Napa and Sonoma counties, recommends that ag businesses create appropriate defensible space around every structure, from barns to sheds. Business owners should also engage in appropriate hardening measures, such as using eighth-inch mesh screening to prevent embers from entering vents.

“I can do site visits and discuss with the business how to create defensible space for their property,” says Norville.

Ag business owners can further minimize risk by keeping vegetation like grass and cover crops mowed or grazed, maintaining irrigation infrastructure, and siting compost away from structures. They should also relocate stored fuels like lumber, fencing materials, and firewood away from structures.

“Ag business owners should prioritize maintaining roads so they can easily evacuate livestock and equipment,” says Norville.

Yana Valachovic, forest advisor and director of the Humboldt-Del Norte County UCCE office, travels around California to assist ag business owners with property evaluations.

Valachovic recommends that ag business owners examine the pathways that fire can travel to a structure. For example, wooden fences are often attached to or are built very close to barns and homes.

“These fences bring fire to the structure like a fuse. An easy fix is to upgrade the 5 feet of fence that attaches to the structure with noncombustible masonry or metal fencing or a noncombustible gate,” says Valachovic.

One of the advantages that farmers and ranchers have is access to water from ponds or storage tanks. Such resources can be very helpful for first responders fighting wildfire.

Public education, funding to compensate for property modifications, and the lending of labor from government offices significantly aids homeowners and ag business owners who want to make their properties more fire-resistant.

Rich Shortall is the executive coordinator of the nonprofit Fire Safe Marin, Marin County’s fire safe council. Shortall says one example of the Marin Wildfire Prevention Authority’s (MWPA’s) recent work is the removal of “fire ladders” close to structures. A fire ladder is high vegetation like tall weeds, shrubs and tree branches that allows a fire to spread up into trees.

“Government agencies can take the lead on creating shaded fuel breaks too. A shaded fuel break is a section of forest in which large trees are left in place. These large trees have their lower limbs removed. The brush below the trees is also removed. Shaded fuel breaks slow the spread of fire,” says Shortall.

The MWPA has created a number of 300-foot shaded fuel breaks in the hills of Novato and between Mill Valley and Fairfax.

Shortall says government agencies can also clear evacuation routes, as MWPA has all over Marin County. They can hold wood-chipper days and specially prune trees on slopes. The steeper the slope, the farther the trees need to be spread apart. The idea is to reduce the heat transfer from trees lower down to those higher up.

In 2020, Marin voters approved funding for fire mitigation measures through Measure C . The 10-year parcel tax levies up to 10 cents per building square foot, with revenues going to operate the MWPA. The MWPA’s 2022-2023 work plan allocates over $20 million for over 100 fire fuel reduction and defensible space projects.

Christopher Thompson is chairman of the board of Napa Communities Firewise Foundation (NCFF), Napa County’s nonprofit to reduce wildfire risk. The NCFF has raised and has been executing about $15 million per year for the past three years on fuel mitigation. It is also applying for significant grants from the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Like the MWPA, the NCFF is removing invasive plants and creating shaded fuel breaks.

“Winegrape growers are on board because smoke taint can also cause a load of grapes not to sell. A number of wineries and growers have bought equipment to fight fires themselves,” says Thompson.

In 2022, Napa County voters voted no on Measure L, a referral to authorize an additional sales tax of 0.25% for 10 years. The measure would have generated approximately $10 million per year for fire protection.

Thompson says property owners can also assist the effort to decrease fire risk by asking the architect they hire to include ignition-resistant construction in their design and the design of defensible space.

“They can advocate for their community leaders to implement the same design criteria in permitting efforts. This will push changes in the architectural community. If you want to change fire behavior, remove the fuels that feed the fire,” says Thompson.

In 2020, Sonoma County’s Measure G, a half-cent sales tax to increase the budget of firefighting agencies, failed to earn the necessary two-thirds voter-approval requirement to pass. In 2021 , the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) provided Sonoma County a $37 million grant that will reimburse local, state and tribal agencies for certain costs related to wildfire risk reduction. Sonoma County is using the money for a multitude of tasks, including creating shaded fuel breaks and trimming undergrowth.

Fire Captain Doug Jones, who works for Cal Fire, commands a crew that covers Colusa, Lake, Napa, Solano, Sonoma and Yolo counties. Jones says property owners can mitigate risk by reducing the amount of flammable vegetation on their property.

“The amount of rain determines how much the fuel load, the amount of grass and brush on a property, increases,” says Jones.

Since it can be hard to get landscapers, property owners should start grass and brush removal in mid spring when the rain stops. They should cut or graze vegetation to be low before the hot days of summer.

Insurance agents are caught in the middle

Insurance agents are extremely frustrated with the change in the market. They see the CDI’s lags and low number of approvals for rate hikes as the reason insurers are leaving California.

“For decades, it was a win-win situation for insurers. Then came climate change and devastating fires. Now California seems like a bad investment,” says Jude Winterhalter, founder of Jackson Square Insurance Associates in Burlingame.

Winterhalter says part of the problem is the reinsurance market has dried up. Insurers are facing higher costs for reinsurance, a measure to transfer some of the risk of loss.

Scott Johnson, owner of Marindependent Insurance in Mill Valley, says the situation will soon lower the number of home sales.

“I think this stalemate could go on for at least five more years. As it continues, insurers are likely to keep moving the metric of what is a fire risk. Insurers are starting to ask for more and more details, even features in the roofline like skylights and solar panels. These could be a ‘hook’ for a fire,” says Johnson.

Janet Ruiz is the director of strategic communication for the Insurance Information Institute, a New York-based nonprofit that speaks for the U.S. insurance industry. Ruiz says insurers want to raise California premiums to a level they see as appropriate.

Ruiz says California homeowners’ insurance premiums are currently in the bottom third in the U.S., with prices averaging at $1,400 per policy. The national average is $1,700. States with tornadoes have an average close to $3,000. Florida, with hurricanes and sinkholes, has an average of $6,000.

“California is one of the more expensive states in which to build. Construction costs have outpaced inflation. Also, the insurance industry is just now being allowed to use forward-looking risk modeling,” says Ruiz.

Ruiz adds that the CDI recently held a workshop to consider allowing the use of forward-looking risk modeling in the rate-making process,” says Ruiz.

Amy Bach is the executive director of United Policyholders (UP), a San Francisco-based nonprofit that represents, informs and advocates for insurance consumers and disaster

victims throughout the U.S. UP is in discussions with state and federal officials and stakeholders across the country to craft a public reinsurance facility or Terrorism Risk Insurance Act (TRIA)-like solution to the property insurance availability and affordability crisis. (TRIA is an example of a publicly supported program that had to be created when insurers stop insuring a specific peril, explains Bach.)

“Insurers are quasi-utilities. They provide a product that is critical to home ownership and the U.S. mortgage system. They cannot operate in an entirely free market,” says Bach.

Bach adds that property owners who mitigate fire risks should be rewarded through discounts and renewal assurances.

“In many states, insurers have succeeded in weakening state oversight of insurance rates. This is not the time for deregulation,” says Bach.

How insurers are using technology

Insurers are just beginning to use new technologies to understand the spread of wildfires. They are making this effort at a time when wildfires are becoming more common and more destructive.

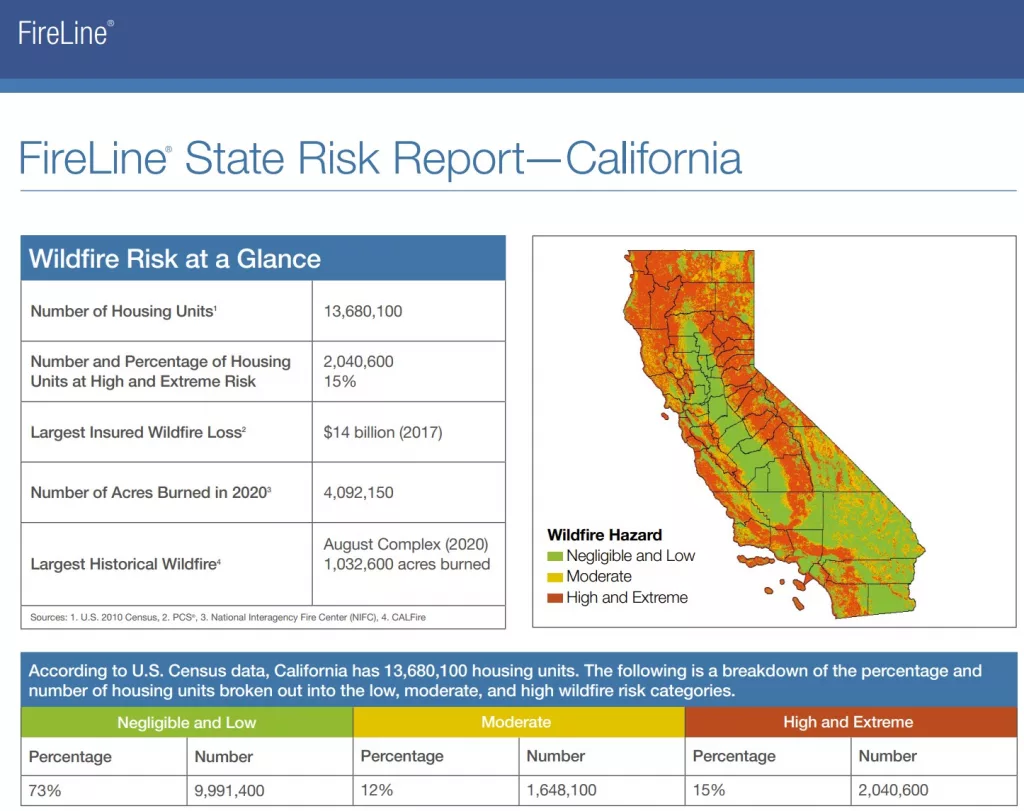

One of the popular programs to assess fire risk is FireLine , developed by Verisk Analytics, a Jersey City software developer.

Dr. Arindam Samanta, director of product management for Verisk Analytics, says FireLine analyzes several sets of data, including a property’s fuel, or combustible material, slope, access, its defensible space zones and structure hardening efforts, as well as community-level fire mitigation work.

“The program also factors in wind patterns, like the Diablo winds, which increase fire risk,” says Samanta.

FireLine helps an insurer to assess wildfire hazard in different locations using the science of wildfires. In addition, Verisk also simulates fires in different locations to create a view of potential losses. Verisk is constantly working on ensuring simulations are objective and consistent.

“We update the data in the software every year, using information from satellites, road imagery and road networks. We collect this information throughout the year. We have a separate service that provides new information to carriers, like the opening of a new fire station in a neighborhood,” says Samanta.

This year, Verisk is working to determine how much community mitigation is working.

“In other words, to what extent will efforts like the creation of several shaded fuel breaks lower the risk of loss for a neighborhood,” says Samanta.

Verisk is also reviewing how fires spread through wildlands. The goal is to see if destruction in wildlands will help insurers understand how fires affect structures.

Anukool Lakhina is the co-founder and CEO of BurnBot, a San Francisco company that builds and operates machinery to clear and burn vegetation.

“We employ a fleet of remotely operated mastication machines that go places where hand crews can’t. These machines can traverse steep slopes, like a slope of 60 degrees, and take out dense vegetation,” says Lakhina.

BurnBot also builds and operates controlled burn machines. These safely and cleanly use fire to ecologically treat vegetation and invasive species. The company developed best practices for these after talks and demonstrations by California indigenous groups, ranchers, utility vegetation management experts and prescribed fire practitioners.

BurnBot’s technologies are an alternative to herbicides, which could affect animals and water sources. They minimize risk to people. For example, a remotely controlled machine would not topple as a bulldozer would over a human crew.

BurnBot is currently discussing with North Bay fire departments and wine grape growers about specific techniques, like burning persistent invasive plants at the roots, and keeping burns at a set temperature to avoid damage to topsoil.

Lakhina says the North Bay is an ideal environment to test and apply fire management technologies because the region has a wide array of microenvironments. BurnBot hopes to showcase the effectiveness of its solutions to encourage communities throughout the three counties to use its tools.

“It would be excellent to see a partnership between communities and insurers. Both sides could pay a portion of the cost for treatments like controlled burns,” says Lakhina.

How leaders are addressing concerns

North Bay leaders on every level are listening to how insurers’ choices are affecting their constituents.

Jeff Okrepkie is city councilmember for District 6 in Santa Rosa, which includes Coffey Park. Okrepkie is also a commercial producer for George Petersen Insurance Agency in Santa Rosa.

Okrepkie says he is seeing cases of under-insurance, with customers buying policies that will not allow them to rebuild after a fire.

“This is particularly true for ag business owners of retirement age. I see them only insuring their home and a guest house. They say if their other structures like their production facility burn, they will retire and stop their business,” says Okrepkie.

Okrepkie says District 6 residents have been extremely vocal in requesting more affordable insurance options.

“We’re right there with residents from other areas who were severely affected by wildfires, from Paradise and Redding down to Santa Barbara and Malibu. We’re screaming for change and no one’s listening,” says Okrepkie.

Victoria Fleming is city councilmember for District 5 of Santa Rosa, which includes Mark West-Larkfield-Wikiup. She says some residents in her district are struggling with extremely high insurance costs.

“One family saw a policy increase of $25,000. I am advocating for more building in parts of Santa Rosa that are not as likely to be devastated by wildfires, like downtown Santa Rosa. This is part of the way I can push for smart development and less potential loss,” says Fleming.

Klobas says the Napa County Farm Bureau has been dealing with insurance concerns by working with the California Farm Bureau. The idea is to develop more support for ag business owners.

“Our feedback helped passage of Senate Bill 11 in 2021. This is the bill that made farmers eligible to insure their structures through the FAIR Plan. Before that, an ag business owner without a policy had nowhere to go,” says Klobas.

The Napa County Farm Bureau is now talking with a variety of stakeholders about policy discounts for fire mitigation on ag business land, among other solutions.

California state Sen. Mike McGuire is the current Senate Majority Leader. He represents District 2, which includes Del Norte, Humboldt, Lake, Marin, Mendocino, Sonoma and Trinity counties. McGuire supports the legislation that would give homeowners discounts for lowering their fire risk.

“The problem right now is the insurance industry is killing these bills in committee. Senate Bill 672 , which I introduced in February, would have prohibited an insurer offering homeowners’ insurance from refusing to sell a policy to an applicant whose property met best practices for wildfire hardening and mitigation. Insurers objected to this bill. Now it’s dead,” says McGuire.

Insurers also objected to a bill that would have developed a commission on home hardening. The group would have researched and shared best practices for preventing fires from escaping beyond a structure.

McGuire describes insurers requesting rate hikes and taking steps to leave the state as holding property owners hostage.

“North Bay residents and people in many other parts of California need common-sense legislation to help them protect and insure their homes. We may have to take this issue to the ballot rather than address it through further bills,” says McGuire.

U.S. Rep. Mike Thompson represents California’s 4th Congressional District, which includes all of Lake and Napa counties and parts of Solano, Sonoma and Yolo counties. Thompson says he has been hearing from constituents throughout his district that the cost and availability of property insurance is a concern.

“Historically, this matter has been handled through the state government. It’s rare that the federal government steps in to make sure coverage is available, as it did in 1968 to provide flood insurance,” says Thompson.

Thompson supports federal legislation that would eliminate tax liability for home improvements that would reduce fire risk. He is also in favor of tax credits that would incentivize homeowners to reduce fire risk.

Thompson adds that members of Congress are watching the health of the California FAIR Plan, particularly as enrollment in the plan grows. Representatives from other states are worried that the trend of limitations and non-renewals will spread to their districts.

“There is talk of a federal program of last resort for fire insurance. Yet at this point fire insurance remains a state issue. It’s not ripe as a federal issue yet,” says Thompson.

For clarification, Bach shared, “TRIA is one model of a publicly supported program that had to be created when insurers stopped insuring a specific peril.”