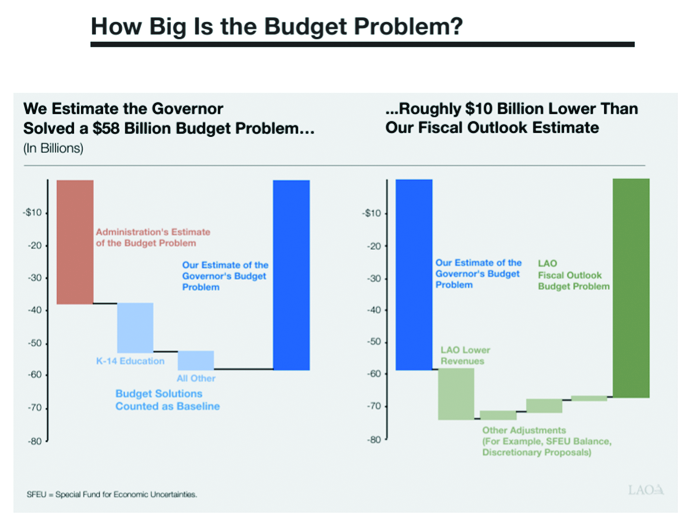

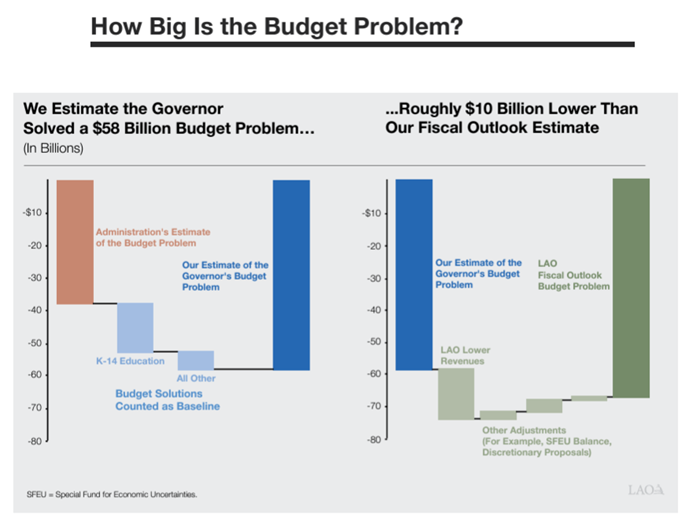

Gov. Gavin Newsom on Jan. 10 put forward his fiscal year 2024-25 budget. The budget had a large deficit (approximately $39 billion; see figure below). California’s Legislative Analyst Office (LAO) predicted a much larger deficit. LAO’s subsequent budget analyses had caveats about California’s ability to solve the budget deficit without significant legislative and practical changes to state government. California’s projected (and current) state budget deficit signals substantial issues. The revised budget in May 2024 will consider some of these issues, but it is essential to see the budget deficit lasting a few years at a minimum.

How California collects taxes is critical in its exposure to prolonged budget deficits. Personal (household) income taxes remain the essential way taxes are collected in California. Slower jobs and wage growth tend to slow down income tax revenues. The boom-and-bust cycle of equity markets generates capital gains tax fluctuations. State government revenues suffer when the stock market stagnates or initial public offering (IPO) activity slows. Corporate income and sales tax are large tax generators also, where property tax revenues are more localized. The federal delay in tax form submissions and payments to October delayed some tax collections and heightened revenue uncertainty as yet another factor. In 2024, collections will be more standard, but the national economy moving more slowly will also affect employment growth and equity market outcomes.

To close projected deficits, California’s state government must also think creatively about expenditures while still maintaining services. State-level government services will likely seek changes that employ more technology, such as artificial intelligence (AI). Labor unions throughout the state and nation are deeply concerned about such a fate. Many jobs may not be easily replaced by a chat service or machine-learning technology, but there are substitution threats from AI, robotics and combinations thereof. It is in labor costs where California’s state government faces its most significant expenses. Decisions may shift current liabilities to pension-system liabilities as one outcome, trading one cost for another.

The following figure is from the Legislative Analyst’s Office on Jan. 23. Regarding budget deficit predictions, it shows approximately a $10 billion difference between the LAO and the California Department of Finance. And this is just year one; the next few years depend significantly on the evolution of tax revenues. Notice in the figure from LAO that the difference between the blue and green columns depicts the estimated revenue problem.

So what does that mean for the North Bay? This means that we should expect businesses to see an increase in the costs of doing business in California. Local governments are likely to consider changes to transient occupancy taxes (i.e., hotel taxes), local sales tax initiatives and reductions in labor expenses as ways of stabilizing budgets while maintaining programs and having marginally more local control over revenues. State-level services are likely to be slower in the short term due to the decision not to re-hire and some reduction in capital projects at state-owned facilities. The lack of spending means less activity and rising pressures on local governments to pick up what is left behind. Demographic change in California needs to be toward more workers and continuing to be a place of new business and global funding for those businesses without some tax code changes. Otherwise, we will remain in a volatile cycle of state-level budgeting.