The 2024 U.S. presidential elections will likely reference the perceived ineffectiveness of economic sanctions against Russia since February 2022. There may also be some rhetoric about how the United States taxpayer spends money helping Ukraine. While recently overshadowed by the conflict and crises in Gaza and the Middle East, we need to watch events in Ukraine with continued concern. One approach to American involvement in both conflicts is using economic sanctions. I have done some work on sanctions, including a book I wrote while on sabbatical at Stanford University. This column will serve as part 1 of a two-part series on these tools of statecraft. (Trade sanctions are considered in brief below.)

Sanctions are reductions of economic activities initiated by a sender country (or coalition) to affect a “target” country. Using its market power in trade or finance, the sender aims to raise costs or reduce revenues in the target economy and perhaps affect political change. A critical factor is that military measures are not taken parallel to economic actions; sanctions are meant to proxy for armed conflict.

A central question in sanctions research is how to measure policy “success” using these restrictions. What would be such an outcome where policymakers could point to the change and say, “We did it” in Ukraine? Historic episodes of sanctions are mainly large economies targeting small ones or specific organizations, but very few are large economies targeting large economies. Success is more elusive when target economies are larger and more globally integrated.

Trade sanctions work similarly to other international trade restrictions such as tariffs and quotas. Such policy change is where protectionist measures—like tariffs (taxes on imported goods) and quotas (restrictions on the volume of imported goods)—differ from sanctions. Reducing or eliminating exports to or imports from a target economy can bring financial problems if the economy lacks other trading partners or is highly dependent on the revenues from trade as income for domestic businesses, government or both.

In the case of Russia, petroleum sales to global oil markets are a vital source of job support, government revenues and personal financial outcomes for the owners/oligarchs tied to Russia’s oil exports. In 2023, approximately 16% of Russia’s gross domestic product (value-added income generated from economic activity that stays within the Russian economy) was based on fossil-fuel exports. That is down from 2022’s results, when oil prices spiked, and more consistent with Russia’s long-term average. The critical issue here is that trade sanctions need to shrink the target economy; Russia’s economy has continued to expand on the surface but is also supported by more defense spending funded by oil sales (sales primarily to China and India through smaller economies such as Armenia and Kyrgyzstan to mask sanction circumvention). As long as oil sales continue, Russia has a war chest.

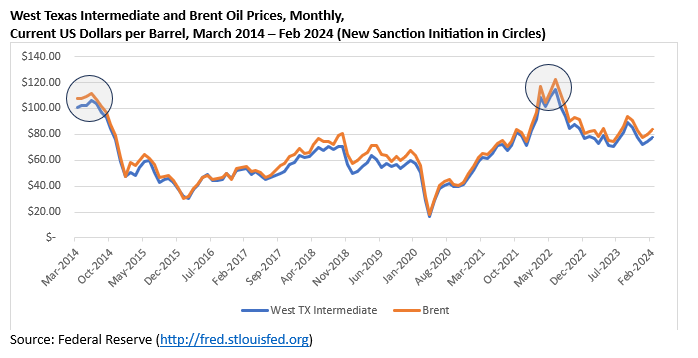

In the North Bay, we feel these effects at the gas station. The fuel cost has stabilized since 2022, and oil prices have returned to similar levels just before the conflict started. However, the time since 2022 has created higher business costs, mainly if your business or employees use fuel regularly (many do). The accompanying figure shows the last 10 years of wholesale oil prices in the United States and Europe. Notice the two prices for crude oil (West Texas Intermediate and Brent for the U.S. and Europe, respectively) are closely related due to a global market for petroleum. The spike in early 2022 is in February and March due to the invasion of Ukraine and the rising demand based on forecasts of surging oil prices (the relatively high prices in 2014 were around the time of the Russian annexation of Crimea). These prices spikes were coincident with new sanctions.

Wine sales and travel can be affected, as rising fuel costs keep air travel more expensive. However, the costs of doing business and living in Europe have continued to be high, so European travelers to the United States have been slow to come back since the pandemic. However, we watch these events to understand how powerful the United States and its allies are in slowing aggression. Next month, we will consider financial sanctions.