A retail store in Toronto, Canada removed its U.S. wines in response to the recent tariff threat. [Shutterstock]

I recently wrote about tariffs, focusing on what tariffs do and are meant to do. The imposition and expansion of U.S. tariffs on the world in general brought theory home in practice quickly. For example, the U.S. wine industry generally exports about 4-5% of its products to other countries, with 90% (perhaps more, depending on wildfires, freezes, etc.) of wine production in California. For some producers, that can be hundreds of millions of dollars lost; reactions have varied, from doing very little (European Union), to pulling products from shelves (Canada), to “tit-for-tat” tariff escalation (China, though an agreement is allegedly being brokered).

As a reminder, tariffs are indirect sales taxes, assessed when imports occur, and then passed on to consumers as higher product prices. One of the key concerns is the amount of so-called “pass-through” and the timing of that price change vis-à-vis inventory levels that have already been imported, or due to timing, could circumvent the recent tariff changes. In April, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) downgraded its forecast for the U.S. economy (and generally for the global economy) due to the shift in international trade conditions and concerns over rising inflation and reduced production levels from new tariffs and retaliatory measures by taxed countries, especially China. Timing and predictability are of key concern from here in terms of both consumer and business adjustments to the new policies.

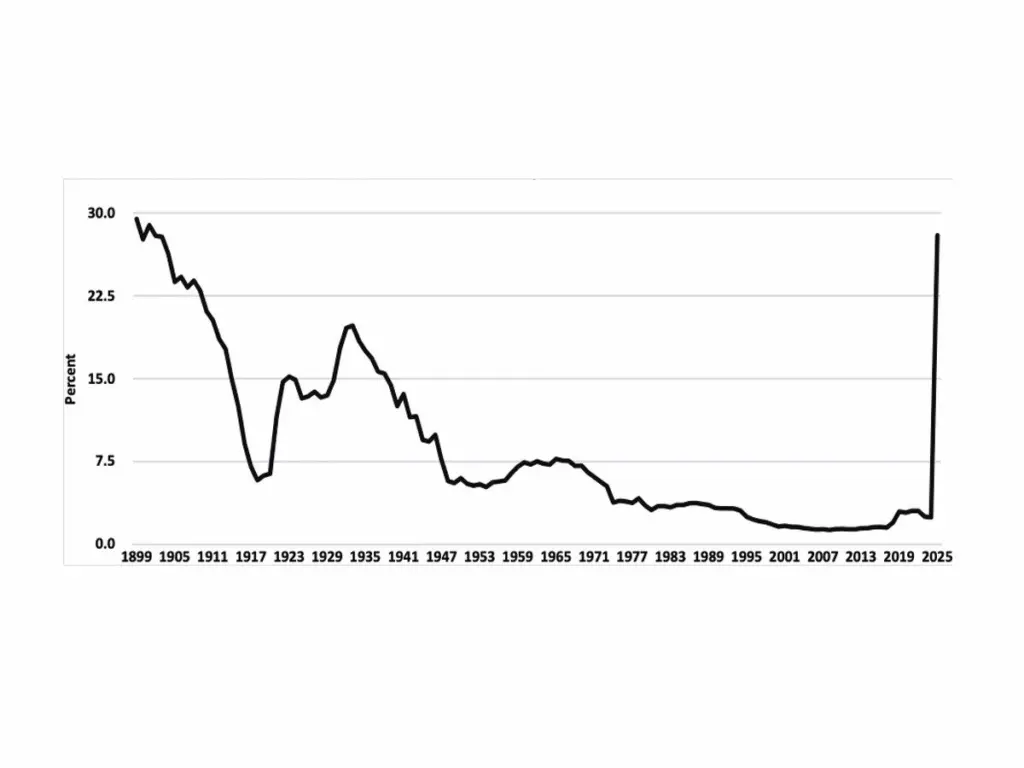

The accompanying graphic has received much attention since April 2: the weighted-average effective tariff rate (AETR) the United States has imposed on global trade since 1899 (the time of President McKinley).

We are now on tourism and wine industry watch for the North Bay. Headlines about stores in Canada removing American wine from their shelves and visitors choosing not to come to the U.S. have already changed some expectations in both wine and tourism regions. California Gov. Gavin Newsom has also gotten involved on the marketing side, where he is letting Canadians (and the world) know California disagrees with the current federal stance and to come to California. This is where a lower dollar value (as marginal as the changes have been) may help market travel.

We must closely watch the longevity of these changes and how stable their current tax regimes remain. Metrics to watch are rising prices: stickers that now appear over printed prices (think changing restaurant menus), for example. Small businesses in the North Bay, especially those that utilize imported goods as critical or diversified parts of inventory or inputs, are more exposed to tariff risks. Restoring manufacturing or sourcing domestic goods more completely takes time. The positive side of tariffs is reorganizing trade flows and incentives for more domestic substitutes and better competitive balance in global markets. History and the deeper economics of manufacturing (one industry of focus in terms of the political rhetoric) suggest that it will not happen soon, if at all, to stabilize the ultimate upswing in consumer prices. For the North Bay, we need to prepare for cost-of-living pressures to rise and the shadow effects of the pandemic’s pinch on small businesses and lower-income households in the North Bay to continue.