Recycling is a way of life for most people. And we feel good that the paper coffee cup, the plastic water bottle, the bags, the papers and the packaging that comes into the house daily can go straight to the curbside bin and disappear into the afterlife of the recycled. So, it’s shocking and horrifying to read about masses of plastics killing wildlife and appearing even in the deepest ocean trenches. We dutifully do our recycling, so statistics about America’s landfills approaching capacity certainly doesn’t apply to us. Does it? Doesn’t all our excess go on to China, or some other country, where they are happy to keep our recyclers in business?

Chances are, your assumptions about the trash you produce, your recycling practices and their consequences have been wrong. You mean well, but you may not be up to speed on the true challenges that come with the products that make life so convenient in our affluent consumer-driven society. But local counties and businesses are working to transform the way we think about and manage the other side of our consumer economy—the “underside” if you will, starting with the word “away.”

A throwaway culture

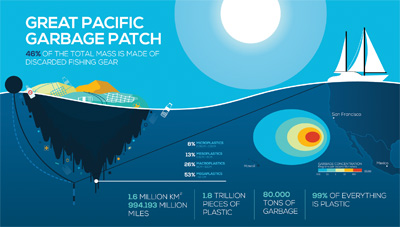

We live in a throwaway culture, but “throw away” is a phrase smart recyclers want us to re-think, along with the word, “trash.” Instead of trash, consider the substance you’re about to discard as material. While it may be of no value to you, it’s valuable material for someone else. “There’s no ‘away,’” says Kevin Miller, recycling manager for the City of Napa. “There’s no other planet, there’s no other place it can go to. It’s got to be handled somewhere, somehow.” Consider, for reference, the devastating reports of plastic pollution on beaches of every continent, washed in from the ocean. If the material doesn’t make it to its rightful destination, it will turn up somewhere on earth, often where we least expect it.

Isn’t recycling the answer? “Well, waste prevention and reduction is the best answer, but short of that, yes, the next best answer is recycling,” says Miller. But the global market for material is even tighter now than it was two or three years ago, when China was a major customer. “In 2016, China bought 61 percent of the world’s recyclables. Then they stopped,” he says. China complained they didn’t want U.S. trash. That is, they didn’t want to receive recyclables mixed with food waste, diapers, and other types of waste. With China shut down and alternatives scarce, businesses suffered. “In Napa, we’ve lost more than $1 million a year in revenue from selling recyclables because of the change in the market,” says Miller. That’s bad, but it could have been worse. “Because we’ve always cared about quality, we’re actually doing a lot better than many places,” he says. “We’ve invested $4 million into our facility for upgrades, including a sorting robot and a $350,000 glass cleaner.” The investment was warranted. “We can’t miss the valuable stuff that is recyclable and has good market value. Also, we have to clean up our act and maintain high-quality standards, or we’re not going to have any buyers. If you don’t have end-users, you just have a collection program, not a recycling program. And we intend to have a recycling program.”

Miller chose this line of work not for the money, but for the good it does for the natural world. Not only is recycling a way to deal with disposed-of products, he says, it’s a way of saving trees and other virgin resources by providing materials for creating new products. “But you’ve got to get the recycled materials to a certain quality standard in order to sell it.”

Where recycling is a way of life

Joe Garbarino, co-founder of Marin Sanitary Service (MSS) has spent his adult life in the business of dealing with what others discard, starting with his high school days in San Francisco. He sees disposed-of material in terms of what “else” it can be, such as jobs, fuel for business or marketable products. “The trash we collect becomes a post-consumer product that we can sell to other people rather than having to bury it.”

Exploring the 105-acre world of Marin Sanitary Service is a journey into the underside of the affluent consumer society. Here, though you may think of it as The Dump, the spirit of the place is not so much about disposal as it is of transition, where items that have ceased to be valuable to some are transformed into materials of worth. The compound has three main areas: the Marin Recycling Center (collection and processing of curbside recycling bins), the Transfer Station (where unrecyclable trash goes to landfill) and the Marin Resource Recovery Center, which has an indoor dump the size of three football fields and an outdoor area where unwanted materials from concrete to tree stumps are sorted and processed for buyers.

When people drive to the indoor dump, and back up their pickups or sedans to the edge and throw their refuse out onto the floor some 10 or so feet below, there’s a palpable feeling of excitement. On the face of it, people are getting rid of their stuff, but the transition process is just beginning. Down below, in a sort of slow-motion dance, men driving bulldozers bear down on various heaps with scavenging zeal to scoop, pile, sort, stack, bale and ultimately sell the result to make it into something new.

The transformation of trash

Inside the Recycling Center, masses of detritus move down conveyor belts as men on both sides, in masks and gloves reach, toss and sort, keeping good material (cardboard and paper) from bad (glass bits, food parts) and separating contaminants (material covered with food waste) from newsprint, which it ruins. One conveyor belt is full of unrecyclable items as Garbarino stops to gesture. “This is nonstop. Nonstop! Look at all the plastic that shouldn’t be in there.” He shakes his head. “The pile grows and grows and grows.” Garbarino understands why China won’t take contaminated recycling, but says China still buys some of his products. “Our newspapers are all going to China, because we bucked the industry trend and sustained our original dual-sort system of collection,” he says. How can that be? “The reason is we’ve added more machinery to keep the glass out and keep it clean. You have to keep up with the times,” he says, reminding us of the refrain that carries through the tour. “It’s not garbage anymore,” he says. “It’s a post-consumer commodity.” You may think of it as trash when you throw it away, but it’s not trash when Garbarino’s finished with it. It’s a product to be sold on the open market.

Progress is something that Garbarino is proud of. “In 1980, I received a grant and started the first county-wide, curb-side program in the United States,” he says. His partners said that because of him, they’d go broke. There’d be no more garbage, just recycling, which would be free. “There is no such thing as free recycling,” he says. “It’s a business. You have to make a profit or you’ll go broke.” Plus, there are regulations. Garbarino’s got to cover his bales of crushed cans, for example, so that any juice or liquid that could possibly be left in the cans would not drain out into the environment. “I’m not going to argue with [the county, city and state],” he says. “If we want a better world, we all have to pay for it.”

In regards to paying for a better world, the pull back of China brought to the surface one striking flaw in America’s recycling system, the need to reduce waste. Another weak link in the chain of progress is knowing what is recyclable. Garbarino continues to point to a stream of trash moving from the recycling bins collected, down the conveyor belt. Candy wrappers, bits of glass, food, garbage. “Look at all the stuff people put in their recycling bins!” he says, dismayed.

How big of a problem is this? “See that box?” Garbarino says, pointing to an enormous 40 cubic-yard container. “We refill that twice a day from the garbage in the recycling bins. Twice a day.” He points to another bin full of large broken pieces of plastic. “This is rigid plastic,” he says. “We can get rid of it, but we have to pay $20 a ton. They’ll grind it up and make new plastic. At least we’re not paying $60 a ton to bury it.” Other materials that show up in the bins, not including bottles, cans, clean paper and newsprint, are aimed for the landfill. This misunderstanding or misuse of the recycling bins is prevalent, despite a two-stream system designed for sorting efficiency both at the curb and at the recycling center. The curbside bins and the trucks are both divided into sections, with papers on one side and bottles and cans on the other. Still, he has problems. “We get about 200 new people coming into the area every month,” he says. “They may be coming from areas that use single stream. Everything in one container. Now, we’ve got to educate them to the dual-sort system. If you’re putting all this garbage in there, it’s hurting everybody.”

Getting to zero waste

Recology Sonoma Marin is an employee-owned, for-profit company that has been operating in one form or another since 1920, when it started out as Sunset Scavengers in San Francisco. It serves 127 communities in California, Oregon, Washington and Nevada and focuses on refuse collection, recovery, processing, as well as marketing and education. Waste-zero manager at Recology, Celia Furber, leads a team of eight, including a publication manager and seven waste-zero specialists. The company educates customers on the importance of reducing waste in addition to recycling and composting as much as possible to bring the waste-load down. It also provides information and training at school assemblies and community events and publishes biannual newsletters in English and Spanish. What’s more, Recology also advertises proper refuse practices in local newspapers, and helps commercial and multi-family-dwelling accounts with technical issues. Recology’s website offers an entire micro-website devoted to proper bin behavior—it’s bright, cheery, illustrated and helpful. Its motto is good for recycling and just about everything else: When in doubt, find out. The one warning in bold letters is: Don’t put plastic bags in the recycling bins. Plastic bags are not recyclable at its facilities—they jam the machines, cost time and money and harm the world. Furber explains that when it comes to recycling plastics, they want to see plastic containers only, not bags, straws or Styrofoam. She points out that the numbers you see on the bottom of containers simply identify the resin codes, and doesn’t necessarily mean an item is locally recyclable. Once customers understand the recycling process, deciding between what’s recyclable and what’s going to the landfill is not hard, and is worthwhile. “Every individual should feel encouraged that each zero-waste change they make is having a positive impact on the environment,” Furber says.

As municipalities and counties grow, so does the amount of refuse that people and businesses generate. At some point, the accumulation of waste will have no viable place to go, according to Miller. In 1989, such a point was reached. “To deal with the inevitable increase in California, a landmark piece of legislation (AB939) was signed mandating that by 1995, 25 percent of the refuse that California cities and counties generate would have to be diverted away from landfill disposal. By 2000, that rate would increase to 50 percent. This would happen through a combination of reduction of disposables—a lofty idea but challenging in practice—or through the growing industry of recycling and composting. How various areas managed to achieve the recommended reduction rate varied according to their demographics and local circumstances. “Right now, the City of Napa is diverting 69 percent,” he says. “We’ve set a goal, (not a mandate) for the City of Napa and the State of California, of 75 percent reduction by 2020.” This is a huge improvement from the time when the law was initiated. “I came to the City of Napa in 1997, and we were at 27 percent diversion,” he says. “So that’s a big change. My personal goal is to get to 77 percent diversion by the time I retire.”

Garbarino fully agrees. “The fact of the matter is that we’ve got to continue recycling to make this world a better place to live,” he says. “The plastic in the ocean is a big problem. There are other issues, too. The gasses that rise into the sky. Climate change. What can we do?” He gestures to his empire of refuse, and to bales of neatly bound recyclables waiting to be resold. “This is what we need to do.” Meanwhile, the real change can begin with consumers doing their part to reduce waste by forgoing the plastic water bottle, the paper cup. Change begins with you.

Recycling Q & A

If something is biodegradable, can you put it in your compost heap?

No, don’t trust labels. Something may be labeled “biodegradable,” but may be blends of bio-based resins and also petro resins and have to go to the landfill.

Do you have to clean items before throwing in recycling bin?

Yes. Rinse them out to clear food and liquid residue before tossing into a recycling bin.

How do you recycle wire clothes hangers?

You don’t. Take them back to the dry cleaners.

Are fluorescent light bulbs recyclable?

Yes, but they’re not to be put in your curbside bin. They contain mercury and are considered hazardous. Take them to a household hazardous waste facility.

Can you recycle electronics? TVs? Computers?

Yes, but not in your curbside bins. Trade them in if your dealer has a program or check with your local recycling center for their drop off location or schedule.

What about batteries, paints, chemicals and cleaning supplies?

They are toxic—do not put in recycling, trash or landfill bin. Instead, consult your local recycling center or businesses that accept batteries, inks, etc.

Can large items such as carpets, furniture or even cars be recycled?

Yes! But don’t leave out for roadside pickup. You need to check in with your local recycling center for what they will take, and for what fee.

3 tips to reduce your waste.

1. Be conscious of packaging when you purchase items. Pick up equipment at the store when you can,  instead of having it shipped: all that shipping material, other than the cardboard, is not recyclable.

instead of having it shipped: all that shipping material, other than the cardboard, is not recyclable.

2. Reduce your paper consumption. Bring your own bag. Get electronic receipts.

3. Purchase consciously and sort carefully. Bring your own mug to the café. Don’t put straws or plastic bags in your recycling.

For more information, both specific and general, visit the Recology Website, www.recology.com

How to drastically reduce your waste

In many communities, local waste haulers are much stricter about what they can accept. Marin County tracks its waste diversion performance annually using the State of California Disposal Reporting System. In recent years, during the economic boom, there has been an uptick in the amount of material going to landfill. This is consistent with historical trends, according to Steve Devine, Waste Management Division program manager for the County of Marin’s Department of Public Works.

What can you do? Watch for new instructions from your local waste hauler about what can and can’t go in your recycling cart. Most importantly, think about what alternatives you can use to avoid creating waste altogether. Devine offers these tips.

Reuse, recycle and compost. For example, if you can afford it, buy milk in reusable glass bottles. Don’t buy beverages in aseptic packaging, which is hermetically sealed in a sterile environment so that liquids, for example milk, or juice can be stored for months without refrigeration. These containers are usually not recyclable. Consider buying household items, sports equipment, etc. on Craigslist, Nextdoor or at Goodwill instead of buying new.

Consume less. When people earn more, they tend to consume more. However, younger generations seem to be shifting toward more experiential “treats” versus material ones. A shift away from “stuff” as fulfillment could significantly reduce the amount of waste going to landfills and reduce greenhouse gas emission. Consider giving a gift such as tickets to a concert instead of another electronic device or choosing ride-sharing services versus buying another car.

Many channels in Marin and most every Bay Area community are promoting messages on recycling—but there are fewer successes in getting people and businesses to reduce waste in the first place. It’s critical that residents and businesses pay attention to the information available from their local waste hauler—as the “do’s and don’ts” published by each collector vary based on who they are able to market materials to.

Consumers have the ability to drastically reduce their “waste footprint.” Using simple alternatives to waste-producing products can make a huge difference. For more information, visit zerowastemarin.org. To learn more about aseptic packaging production processes, go to: discoverfoodtech.com.

Invaluable Resource

What goes in, what stays out?

For a look at some specific types of throwaways and what they’re doing to our homes, our communities, our streams, air and oceans the California Product Stewardship Council (CPSC) is an invaluable resource. Their home page, listed below, gives a visual menu of the typical items we don’t know what to do with after they expire.

Fluorescent bulbs. Where do they go? Trash? Recycle? No! Fluorescent bulbs have mercury in them. When they break, mercury, a health hazard, is released. Look for the place near you that can take them.

Packaging. CalRecycle, which is part of the CPSC, lists packaging as taking up one-third of the 66  million tons of solid waste generated each year by Californians. So do you throw the whole box, Styrofoam fillers and bubble wrap in the recycling bin? No! Look below for a place that will take them.

million tons of solid waste generated each year by Californians. So do you throw the whole box, Styrofoam fillers and bubble wrap in the recycling bin? No! Look below for a place that will take them.

Carpet. Every year, Americans discard about 4 billion pounds of carpet, a huge greenhouse gas contributor. Don’t toss it in the recycling bin, but take it to a facility that can handle it.

Plastics.

For a glimpse of what plastic waste does to Pacific islands, visit calpsc.org.