Predictions that an El Niño year could ease California’s current drought doesn’t put an end to all the issues.

Parched landscapes, dry creek beds and raging wildfires had North Bay residents on edge and craving rain by the time fall arrived, so reports that a strong El Niño was forming off the west coast of South America created high hopes for a wet rainy season. The news makes the likelihood of precipitation in the winter months promising, but whether it will deliver enough water to help offset the effects of four years of drought is another story, because if one thing is certain, it’s that rainfall is less than predictable.

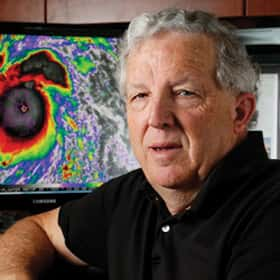

Parched landscapes, dry creek beds and raging wildfires had North Bay residents on edge and craving rain by the time fall arrived, so reports that a strong El Niño was forming off the west coast of South America created high hopes for a wet rainy season. The news makes the likelihood of precipitation in the winter months promising, but whether it will deliver enough water to help offset the effects of four years of drought is another story, because if one thing is certain, it’s that rainfall is less than predictable.Jan Null, certified consulting meteorologistwith Golden Gate Weather Services in Saratoga, is cautiously optimistic about the possibility of winter rain and observes that the current El Niño has continued to build in strength since April. He says it tilts the odds in favor of substantial rainfall but doesn’t guarantee it. He explains that El Niño is a weather phenomenon that wasn’t very well known before the 1980s, but after that, satellite images improved and the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) started using buoys to collect information for its data center. The accumulation of information lets meteorologists look at the climatology of past events but, “That’s climatology of past events and not a forecast,” says Null. “There’s not proven skill in long range forecasts.”

On average, some form of El Niño occurs every two to seven years. They range from weak to very strong, and the biggest ones are rare. “We’ve had only two very strong El Niño events in 65 years,” says Null. “This would be the third.” The previous pair of strong El Niños on record are for 1982 and 1997, and they had significantly different results. “We get flooding whenever we have very intense rainfall in a concentrated period of time, but it doesn’t have to be an El Niño for flooding to occur in California,” says Null. That was the case in 1982, when Northern California had periods of extremely heavy rain and, according to NASA, sustained $2.2 billion in damages. In contrast, “In 1997, we received twice the normal amount of rainfall, but didn’t have a lot of major flooding,” he recalls, explaining that the precipitation was spread out over a longer period of time, so the damage incurred was far less, totaling $500 million.

On average, some form of El Niño occurs every two to seven years. They range from weak to very strong, and the biggest ones are rare. “We’ve had only two very strong El Niño events in 65 years,” says Null. “This would be the third.” The previous pair of strong El Niños on record are for 1982 and 1997, and they had significantly different results. “We get flooding whenever we have very intense rainfall in a concentrated period of time, but it doesn’t have to be an El Niño for flooding to occur in California,” says Null. That was the case in 1982, when Northern California had periods of extremely heavy rain and, according to NASA, sustained $2.2 billion in damages. In contrast, “In 1997, we received twice the normal amount of rainfall, but didn’t have a lot of major flooding,” he recalls, explaining that the precipitation was spread out over a longer period of time, so the damage incurred was far less, totaling $500 million.Null explains that El Niños differ because other weather events are happening at the same time. “An El Niño isn’t working in a vacuum,” he says, so although we might get storms, the El Niño can’t necessarily take the credit. “El Niño is like the star player in a sports game on some performance-enhancing drug,” he says. The athlete was outstanding before taking the drug, so after, you don’t know whether the performance is the result of his natural talent or the effect of the drug. “It’s the same with El Niño,” says Null. “It’s supercharged, what’s going on in the atmosphere,” he adds, so while the odds favor an above-average rainfall year, it’s not a sure thing.

“We’ve had three-quarters of normal rainfall totals over four years. That means we’ve lost a whole year’s rainfall. We need to make that up,” says Null. “The state needs 150 to 200 percent to erase the rainfall deficit,” he adds, observing that the problem isn’t just the lack of rainfall. It’s the impact it has on various activities. “The weather has a huge impact on the U.S. economy,” he says. “Nobody has the solution. If someone could figure it out, they’d own the world.”

Close to home

Ongoing rainfall is a must to replenish the North Bay’s reservoirs, and the need after four straight years of drought is without question. Brad Sherwood, community and government affairs manager for Sonoma County Water Agency (SCWA), a wholesaler that provides water to nine cities and water districts in Sonoma and Marin counties, reports that, at the end of September 2015, Lake Sonoma and Lake Mendocino, where the agency stores its drinking water, were at 73 percent and 57 percent of capacity, respectively. With water levels visibly low, “We need at least above-average rainfall in the winter and spring months—32 inches is average annual rainfall in Santa Rosa, for example,” he says.

In Marin County, where much of the water comes from seven reservoirs in the Mount Tamalpais Watershed, the situation is somewhat less severe. “In 2014 and 2015 we had a couple of big rainstorms that filled our reservoirs. We have a very productive watershed,” says Michael Ban, environmental and engineering services manager at Marin Municipal Water District (MMWD), which supplies water to the southern and central areas of the county. “We have about a two-year supply in the reservoir. Without those storms, we likely would have had to roll out mandatory cutbacks,” he says.

In Marin County, where much of the water comes from seven reservoirs in the Mount Tamalpais Watershed, the situation is somewhat less severe. “In 2014 and 2015 we had a couple of big rainstorms that filled our reservoirs. We have a very productive watershed,” says Michael Ban, environmental and engineering services manager at Marin Municipal Water District (MMWD), which supplies water to the southern and central areas of the county. “We have about a two-year supply in the reservoir. Without those storms, we likely would have had to roll out mandatory cutbacks,” he says.The ideal supply is four years’ worth of water, so even though it has adequate supplies for the moment, Marin needs rain: “2013 was the lowest rainfall year on record for us—just 11 inches,” says Ban. He adds that an ideal winter would be a normal rainfall year, with rain concentrated between November and March, and even though it’s below average, 40 inches would be enough.

“Timing of rainfall is critical,” says Sherwood. “We need a steady stream of rainfall—not one large storm—due to how the reservoirs are operated under the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ flood control operation manual.” He explains that the manual requires sufficient water be released to retain flood control space, and so, he says, “A rain pattern with storms coming in waves throughout January into April would be best.”

Impact on business

Water shortages have all kinds of impacts. “I think it’s broad-based,” says Ben Stone, executive director of the Sonoma County Economic Development Board. “Agriculture and all its manifestations will be most affected,” he says, pointing out that drought results in higher costs. “For instance, hay prices have already skyrocketed,” he says, but farmers still need to feed their animals, so other costs go up. One of the results is that restaurants have to pay more for the ingredients that go into their dishes, which means higher menu prices.

Water shortages have all kinds of impacts. “I think it’s broad-based,” says Ben Stone, executive director of the Sonoma County Economic Development Board. “Agriculture and all its manifestations will be most affected,” he says, pointing out that drought results in higher costs. “For instance, hay prices have already skyrocketed,” he says, but farmers still need to feed their animals, so other costs go up. One of the results is that restaurants have to pay more for the ingredients that go into their dishes, which means higher menu prices.Stone adds that drought also has a major effect on tourism, citing golf courses as an example. Players don’t want to play on dry fairways and greens, so operators who’ve been using fresh water have to make changes. Hotels have the same problem. “Aesthetics are an issue, because guests don’t want to see deteriorated landscaping,” says Stone, adding that health care feels the impact as well. “Washing the linen in hospitals, restaurants, hotels and other institutions is an issue,” he says, not including the water necessary for day-to-day operations. He reports that 10 percent of the local workforce is manufacturing, which often requires water for processing, so it’s affected too, along with others, such as the wine industry and nurseries.

He believes that when it finally does rain, recovery will vary according to the industry, but the current concern is prolonged drought. “We’re facing unprecedented extreme conditions,” he says. He observes that, if we get substantial rainfall, then water agencies could ease restrictions, but cautions, “Be careful what you wish for,” because heavy rains could cause flooding, which would result in another set of problems.

“A significant El Niño in the North Bay this year would be both a blessing and a curse. The blessing is that we badly need the rain; the curse for contractors is that it would shorten the building season.” says Keith Woods, CEO of the North Coast Builders Exchange, explaining that deluges and downpours have a big impact on construction. In California, “You have a somewhat predictable rainy season,” he says, so the building industry expects rain from November to March and plans accordingly. Because April to October is the building season, contractors plan other activities for the off months. “Ideally, we want a rainy season when you can do other things,” he says.

“A significant El Niño in the North Bay this year would be both a blessing and a curse. The blessing is that we badly need the rain; the curse for contractors is that it would shorten the building season.” says Keith Woods, CEO of the North Coast Builders Exchange, explaining that deluges and downpours have a big impact on construction. In California, “You have a somewhat predictable rainy season,” he says, so the building industry expects rain from November to March and plans accordingly. Because April to October is the building season, contractors plan other activities for the off months. “Ideally, we want a rainy season when you can do other things,” he says.Woods explains that if heavy rain occurs out of the usual November through March period, it shortens the timeframe for building. In addition, heavy, sustained rain can create muddy conditions and impromptu ponds, impacting paving, building roads and digging ditches because mud makes it difficult to prepare a building site. “It can make it very difficult to get something built,” says Woods. In addition, out-of-season rainfall can play into the permit process, because it can delay the work. When combined with extensive rain, it could cause a builder to miss the construction season entirely.

Drought conditions also have an effect on construction, because they bring the potential of local governments calling for moratoriums on water permits for commercial or residential building in their communities, and building can’t go forward without access to water. “There’s always a fear of that,” says Woods, although suggestions for moratoriums haven’t materialized during the current drought. “Our position is that a community ought to do everything else before taking such a drastic step as a moratorium on building. The Builders Exchange, as well as the entire business community, is a strong supporter of conservation efforts,” he says. “A moratorium can wreak havoc on our economy,” he adds, pointing out that if building stops, a moratorium affects more than just contractors. It affects architects, engineers, realtors, building suppliers, title companies, lending institutions and countless other businesses.

One of the worst results of the drought is wildfire, and Woods estimates that September’s Valley Fire in Lake and Napa counties destroyed an area roughly three times the size of Santa Rosa. With the loss of more than 1,900 homes and structures, rebuilding is a necessity. “We’re going to do everything we can to help the victims rebuild their homes and their lives,” he says.

Change of thought

In Wine Country, vintners can’t take the time to wait and see how the prediction for a stormy El Niño winter will play out. “We have to button up our hillside vineyards and be mindful of what can happen,” says David Graves, co-founder of Saintsbury Winery in Napa. He explains that measures to prepare for a large amount of rainfall had to be in place by October, because intense downpours can cause soil loss and erosion. “We had to make sure our storm water systems were in place and ready to go,” he says, explaining that some of what’s required is the same as what a homeowner would do and is common sense.

In Wine Country, vintners can’t take the time to wait and see how the prediction for a stormy El Niño winter will play out. “We have to button up our hillside vineyards and be mindful of what can happen,” says David Graves, co-founder of Saintsbury Winery in Napa. He explains that measures to prepare for a large amount of rainfall had to be in place by October, because intense downpours can cause soil loss and erosion. “We had to make sure our storm water systems were in place and ready to go,” he says, explaining that some of what’s required is the same as what a homeowner would do and is common sense.If the rains do come, “A wet winter from El Niño doesn’t mean it’s business as usual,” says Graves. “It’s part of an ongoing story about climate change. We can’t get enough rain to make up the deficit in one season. It does mean that the north coast soils will be replenished,” he observes, but adds, “A part of me says be careful what you wish for. When it comes to the drought in our part of the world, we sort of dodged the bullet. We had enough rain events that we could collect water and store it,” he reports. “We haven’t seen many dry wells yet. We’ve learned that it’s really important to monitor our groundwater levels.”

In the Los Carneros Water District in southern Napa ounty, property owners are taking a proactive approach to alleviating the stress of drought in the future by building a new recycling system. “We have more than 20 miles of pipe all over Carneros,” says Graves, explaining that the region came together to build a system of pipes to deliver recycled water, thus creating climate resiliency and building in extra capacity. Graves reports that the property owners agreed to tax themselves to build the infrastructure, and the vote to build the recycling system got 95 percent approval.

“The majority of the costs are paid by us,” he says, pointing out that the cost of the water and the system for recovering it is small compared to the value of winegrapes. It avoids climate disruption and, “It’s like an insurance policy,” he says.

“Our consciousness about water use has to change forever,” he adds. “We shouldn’t call used water ‘waste water.’ We have recovery plants. We don’t live in a place where we can use water once and throw it away.” For him, in an ideal winter, “We would have lovely Irish levels of rain from November to April,” but that’s not likely.

Northern California is flood and drought country, so prolonged dry spells and deluges of rain are inevitable. Awareness is growing that periods of extreme weather in Northern California’s Mediterranean climate are a certainty. “People are really making wholesale changes in the way they view and use water,” says MMWD’s Ban, who reports that conservation efforts are making a difference as people take measures such as changing landscaping to incorporate drought-tolerant plants and switching to toilets and other appliances that use less water.

Sherwood sees the same response in Sonoma County. “Summer peak demand dropped from 60 million gallons per day to around 40 million gallons per day this year,” he says. “We’re seeing great conservation efforts taking place. Our community has responded extremely well so far, exceeding state water conservation goals.”

With a commitment to conservation and creative thinking about their use of water, North Bay residents are leading the way in finding ways to live with the weather and preparing to face whatever comes next. El Niño or not, they plan to be ready.

El Niño and Drought

El Niño is the periodic warming of the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean and can occur in water adjacent to the South American coast or closer to Hawaii. It’s the biggest periodic weather factor in the world and can be weak, moderate or strong. Drought is a prolonged period of unusually low rainfall, often with higher than normal temperatures, which results in water shortages.

The Buzz on Bees

Bees are an essential part of the ecosystem and play a vital role as pollinators in agriculture. Drought, however, puts them at risk. Bonnie Morse of Marin County’s Bonnie Bee & Company says that feral colonies face particular challenges because they must forage, compared with managed colonies, which beekeepers can help feed. When the soil doesn’t have enough moisture, the nectar flow stops, depriving the bees of food. She reports that in areas such as Nicasio and the San Geronimo Valley, “The bees were finding little to no food in the middle of April.”

Bees build their colonies in early spring and heavy rains can prevent them from going out to get food for their young. “During prolonged rainy periods they can’t get out to get the groceries,” says Morse. Annual losses of bees are already an issue as a result of other factors, and extreme weather has the potential to compound the loss.

Morse teaches classes on beekeeping and manages hives for others, and she’s currently involved in organizing a two-day national and international collaborative working conference, Audacious Visions for the Future of Bees and Beekeeping, to explore ways to help bees prosper.

Lack of Appeal

First appearances are everything in real estate, so curb appeal carries a lot of weight. Karl Hoppe, a real estate agent with Marin Land Company in Tiburon, says purchasing a house is emotional, and people react to what they see. “If someone is looking for a house, I’m not sure they’re going to consider the drought,” he says. “If it’s going to kill all the shrubs in front of your house, it might a problem for a seller. If the front yard is landscaped with drought-tolerant plants already, that would be preferable to seeing water-hungry, dead plants.” In the case of heavy rains, a potential buyer fearing landslides might ask for a soil report from an engineer before going forward, but, ultimately, a buyer in the market for a house is going to purchase one. The weather won’t be a deterrent, but it could affect the final choice.