The unquestioned star of this market is Apple, which closed 2011 at a price of $395 per share and, as I write this, last traded just below $600, a rise of 50 percent in 11 weeks. Shares of the company have gained nearly 600 percent from the $85 they were trading at when Steve Jobs first announced the iPhone in January 2007. Apple’s “market cap” (number of shares times the price of the last trade) is now more than $560 billion, giving it the largest market cap of any company in the universe. Every mutual fund manager now seems to hold a position in Apple regardless of his fund’s mandate, and Apple alone makes up 4 percent of the market cap of the entire S&P 500 Index.

These points remind me of the old Wall Street adage, “Trees don’t grow to the sky.” If Apple’s stock were to maintain the same pace of growth over the next five years, the price would rise to more than $4,000 per share and the company’s market cap would exceed $3.7 trillion. It’s not too hard to see the absurdity there.

But the current market rally isn’t just about Apple. The more important story is the performance of the market’s more volatile stocks. For several decades, market professionals have bought into the academic theory known as the “Capital Asset Pricing Model” (CAPM). According to CAPM, the risks and returns of any asset class are positively correlated; this means that, to achieve greater returns, one must undertake greater risks.

Volatility of returns is commonly used as an indicator of risk. Under CAPM, there should be a positive correlation between stock volatility and stock returns. This model is now under question. GMO, the well-respected Boston adviser to major endowments and institutions, published a paper in 2006 reflecting its conclusions from in-house research that “volatility works backwards for stocks,” as did most other common risk factors. (See “Do Investors Understand Risk?” Wealth Wise, Dec. 2006). In simpler terms, taking on more equity risk means achieving lower returns.

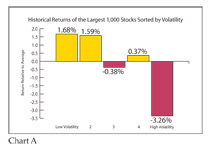

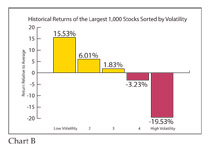

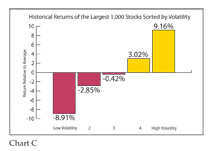

Recent academic research backs up GMO’s contentions. In a paper published in the Financial Analyst Journal in January 2011, a review of 45 years of market data by Baker, Bradley & Wurgler confirmed the GMO findings. Stocks exhibiting the least volatility outperformed those exhibiting the most volatility by almost 5 percent annually. Here is a chart summarizing the Baker, Bradley & Wurgler findings based on dividing stocks into five quintiles by market volatility:

Our firm’s Dividend Growth Portfolio is consciously managed to maintain lower risk, both by focusing on lower volatility stocks and combining them in ways to lower the overall portfolio volatility even further. So far this year, our portfolio has lagged the S&P 500 Index by more than 3 percent. We have experienced significant periods of sub-index performance, even for entire years (2006 and 2009 are good examples). We see nothing in market behavior over the first 11 weeks of 2012 to lead us to change our thinking.

And no, we don’t own Apple.