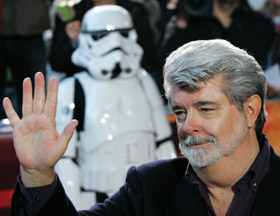

The week after George Lucas decided he’d had his fill of Marin politics and hostile neighbors, the Marin County Board of Supervisors did something never before seen in Marin.

The week after George Lucas decided he’d had his fill of Marin politics and hostile neighbors, the Marin County Board of Supervisors did something never before seen in Marin.It publicly begged a billionaire.

At a special meeting, a parade of speakers walked up to a mic and pleaded, cajoled and beseeched Lucas to reconsider his decision to walk away from Grady Ranch.

The meeting was webcast, and it’s said that Lucas was watching at Skywalker Ranch. It wasn’t as cerebral as a PBS pledge break nor as slipshod as an old Jerry Lewis Telethon…but it didn’t work, either.

The abandoned Lucasfilm Grady Ranch project would have generated 690 construction jobs and 270 additional jobs in Marin County for every 100 jobs created at Grady Ranch. Grady itself was slated for 340 jobs, which means that, all told, the project would have added at least another 850 jobs in the North Bay.

Let’s talk cash money. How about $270 million in business revenues plus $10 million in tax revenues during the construction period? After the digital film studio was completed, the tax revenues would have swelled to $44 million per year. At a time when we can’t seem to keep libraries open and there are potholes the size of farm animals in the middle of the street, that cash would have been just fine. All this data is courtesy of the Marin Economic Forum.

It’s irresponsible to do a “Game Changers” issue and not, to borrow a line from Lucas’ “Star Wars” franchise, “go to the dark side.”

While we celebrate pioneering companies and business leaders who’ve helped create a vibrant North Bay economy, it’s instructive to understand that failure also shapes the economic landscape.

The Grady Ranch post mortem has been somewhat dwarfed by the $4.1 billion 2012 sale of Lucasfilm to Disney. To a large extent, the discussion has centered on the assigning of blame for George Lucas’ decision to pull the plug on the project and instead turn the 230 acres over to the Marin Community Foundation for the development of workforce housing.

The impact of this episode is still in the crystal ball stages, but some educated guesses are in order. But before we get there, let’s understand what the Grady Ranch project was and where it came from. Originally zoned by the county of Marin for residential development with as many as 232 homes allowed, the land was bought by Lucas many years ago and the residential development never took place.

The proposal

Grady Ranch was to be built on the site of a former dairy farm off Lucas Valley road. It was to be a state-of-the-art, 260,000-square-foot digital film studio constructed in the Mission style, with two 85-foot-high towers. The facility would have included a pair of indoor sound stages, an outdoor stage, screening rooms, an employee café and a general store. A guest residence would also have been built and a small vineyard and wine cave were also included in the plans. The project received its initial approval in 1996, but Lucas elected not to build right away.

The project came back to the county in 2011 after minor changes were made, and the planning department and planning commission both gave the project two thumbs up.

While Lucasfilm has a well-earned reputation for promoting a culture of secrecy and keeping projects and products under wraps, when it wants something that requires public input, the company has the ability to court stakeholder groups—Grady Ranch was no exception. Though George Lucas was used to getting his way, he’s also enough of a pragmatist to understand that successful projects need local support. His company had been talking on and off for years to its neighbors on Lucas Valley Road, so when Grady Ranch came out of hibernation, the project itself wasn’t a surprise.

That doesn’t mean everyone joined hands to sing “Kumbaya,” however. Some residents belonging to Lucas Valley Estate’s Homeowner’s Association, led by Liz Dale, didn’t relish the idea of a film studio being added to the neighborhood. The neighbors cited concerns about everything from traffic safety to the lights from the compound taking away from their enjoyment of the night sky.

The Marin Municipal Water District told Lucas he needed to pony up $2 million prior to the project being built to front infrastructure costs. The Regional Water Quality Board expressed concern regarding restoration work on the creek and watershed, which Lucas had already agreed to undertake and pay for to the tune of as much as $70 million.

Some neighbors wanted the county to understand they had reservations about the project, so they hired an attorney with a background in environmental law and filing lawsuits regarding the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). In turn, the lawyer produced a 50-page report containing the neighbors’ concerns over the project and possible shortcomings from a CEQA standpoint and turned it over to the county.

The county interpreted the document to be a precursor to a lawsuit over the project. The board of supervisors tabled the vote until it could look at the report and better gauge what it meant.

The decision

On April 10, 2012, George Lucas decided he wasn’t waiting for the board’s decision. He was done with the neighbors, done with the project—and done with the county. “The level of bitterness and anger expressed by homeowners in Lucas Valley has convinced us that, even if we were to spend more time and acquire the necessary approvals, we wouldn’t be able to maintain a constructive relationship with our neighbors,” the company said in a statement. “We love working and living in Marin, but the residents of Lucas Valley have fought this project for 25 years, and enough is enough. Marin is a bedroom community and is committed to building subdivisions, not businesses. Many years ago, we tried to stop the Lucas Valley Estates project from being built, and now we have a subdivision on our doorstep.”

Shifting gears, Lucas announced his intention to transfer the land to the Marin Community Foundation for workforce housing, affordable housing’s better-dressed cousin. Last December, the foundation put out a request for qualifications to developers for the project, according to Dr. Tom Peters, CEO of the foundation.

In June, however, the foundation announced that it was stepping away from Grady Ranch. Peters said that the project, with a price tag of between $120 million and $150 million, could require as many as 15 different sources of financing, despite the fact that Lucas is turning over the property. “I’m disappointed that the economics are so challenging and sincerely hope that other models can be developed that will bring the project to fruition,” says Peters.

A spokesman for Lucas’ company said it remains dedicated to getting affordable housing done on the site, despite the Foundation dropping out.

As many as 20 developers have said they’re interested in the project.

There were a few who said privately that the decision to develop Grady Ranch for workforce housing was just Lucas getting even with the neighbors who opposed his project. In a New York Times story, Lucas was quoted on the very subject, saying there’s a real need for more affordable housing in Marin and that he was only trying to do something good. “I’ve been surprised to see some people characterize this as vindictive. I wouldn’t waste my time or money just to try and upset the neighbors.”

The same story quoted Carolyn Lenert, who heads up the North San Rafael Coalition of Residents, as registering some concern over how workforce housing at Grady Ranch might impact Marin. “It’s inciting class warfare,” Lenert said.

Lucas might not have been looking to intentionally make the neighbors unhappy; perhaps it’s just a happy bonus.

“I find it a little funny,” Peters says. “The people who say he did it as some sort of way to get even with the neighbors don’t know George Lucas.”

At the time, reaction to Lucas pulling Grady Ranch back ranged from shock to name calling and disappointment. Then Mill Valley Mayor Gary Lion told KCBS Radio, “We don’t want this be held up to all businesses as an example of how difficult it is to do any good business in Marin County.”

Marin Supervisor Judy Arnold told the Marin Independent Journal that Lucas is “one of the best neighbors anyone could ever have. The loss of millions in revenue we would have coming in from this key targeted industry…is just unfathomable.”

Brian Crawford, the chief of Marin’s Community Development Agency, said he was stunned at the missed opportunity: “It’s a sad day for Marin County.”

The reactions

It’s been 15 months since Grady Ranch went away, not really enough time to heal the wounds, but perhaps enough to begin gauging the damage to Marin County’s business reputation. It’s more than fair to say that even before the Grady Ranch debacle occurred, Marin was seen by many outsiders (and more than a few insiders) as a challenging place to do business. Not only is it a place with high costs, it has planning and approval processes that can be positively glacial. This is to say nothing of the fact that the law of the land is that Mother Nature is sacred, so some projects will never make it past the back of a napkin.

But, on the other hand, Marin is centrally located in terms of product and services distribution, has an educated workforce, and its demographics are attractive for a number of sectors.

Supervisor Arnold has had the benefit of a look back at what took place. She organized the special hearing of the board and helped line up members of the community to essentially beg Lucas to change his mind—which, of course, didn’t happen. “In hindsight, if we faced the same issue again, I think we’d be inclined to vote in favor of the project and let the chips fall where they may with the neighbors and any lawsuit they might have brought. What happened was heartbreaking, a huge loss of us as a county and as a community.”

While the supervisors have taken their share of barbs for not taking the very action that Arnold describes here, she defends her cohorts on leaving the vote for another day. “We asked Tom Forester, who represented Lucas, if not taking the vote that day was an issue and he told us it was fine, leave it with him and they’d look at it, too.”

Looking forward, she says the lesson to be learned from Grady Ranch is two-fold. She’s now calling for an economic impact report to be done alongside any major project being considered, “and the economic piece needs to be done early, so there’s plenty of time for comments.”

The other wisdom that comes from losing Lucas is that there are times when the county needs to do a better job looking at the big picture. “Big issues like this transcend the normal approach. We need to understand everything that’s at stake.”

At some future date, the issue of workforce housing at Grady Ranch will come before the board, and Arnold and company will be asked to vote once again. “I’m sure you’ll see a fast track approach on that. It will be like speed dating,” Arnold says.

Arnold’s enthusiasm is commendable, especially in light of the prevailing attitudes when it comes to workforce housing in Marin. Not to put too fine a point on it, but in general, workforce housing in the county is always considered a good idea. It becomes a much better idea when it’s to be located in a neighborhood other than the one you live in.

Her compatriot on the board, Steven Kinsey, called the Grady Ranch outcome, “a tremendous shock to the system.”

Kinsey laid the blame for Grady Ranch at the feet of the Regional Water Quality Board and the neighbors, but says the more important issue for the county going forward is to bring economics into the process in a more substantial way: “We just got done voting to fund the Marin Economic Forum $150,000 per year. We need them to weigh in on projects and act as an ombudsman.”

The fallout

Lucas’ decision to walk away from Grady Ranch has had an impact beyond the county. Stephanie Lovette, economic development manager for the city of San Rafael, says she often begins her dialogs with new businesses considering her city this way, “We’re the city of San Rafael, not the county of Marin.”

Lovette says that companies sometimes are scared off by Marin’s reputation, and Grady Ranch won’t help that issue. “The sad part is, we’re unlikely to see another company like Lucasfilm looking to do something like that here, which is tragic.”

She says Grady Ranch is a challenging site for workforce housing, because it’s not in an urban center or along a major transportation route. “But if we can get some housing out there, then at least some good will come from this.”

Peters, whose organization was originally set to ride herd on the project, says the whole notion of the site not being right for a workforce housing project is overdone. “The nice thing about it is it was already zoned for housing. It’s in the same neighborhood as 700 homes, and none of those people feel isolated. There’s water and power out there. I was on the property a little while ago with some of the Lucas staff, and the cable company was out there putting in T-1 lines.”

Russ Colombo, president of Bank of Marin, who’s lived in the county his whole life, says Grady Ranch illustrates the fundamental issue: “Balance. We [Marin] don’t get the idea that it’s great that we live in a place that’s beautiful to look at, but we can’t say it’s OK to not ever build anything. We need to understand that without building something—without businesses being able to grow—our economy won’t move forward, either.”

He says sometimes he worries about sounding like the banker calling to pave over paradise, but Grady Ranch demonstrates that Marin County needs to deal with the issue now and not wait for the “next Lucas.”

“People need to understand that Marin lost Lucas twice, once to the Presidio in San Francisco and again with Grady Ranch. That’s what comes from not learning the lesson the first time.”

George Lucas Timeline

In many ways, George Lucas and Marin County were made for each other. Lucas got his start with the 1971 science fiction film “THX 1138,” co-written by West Marin resident (and Academy Award winner) Walter Murch. But he made a name with 1973’s low-budget “American Graffiti,” famously filmed in Petaluma and Tamalpais High in Mill Valley.

What’s more, Marin is a wealthy enclave that’s quite insistent on how things should work, while Lucas is a billionaire who’s independent to a fault.

1975 Lucas starts Industrial Light and Magic in Marin. It goes on to win 16 Oscars.

1977 “Star Wars” debuts and sets box office records, grabs eight Oscars and lets Lucas make his next move.

1978 Lucas quietly buys 2,500 acres in Nicasio that, seven years later, would become known as Skywalker Ranch. The headquarters for Lucas’ growing empire, Skywalker is off a two-lane country road where commercial development isn’t allowed. But the landmark film facility is built by keeping the development to a minimum and donating hundreds of acres for open space. This would become Lucas’ go-to move as he developed other Marin facilities.

1979 Lucas renames Sprocket Systems, the R&D arm of Lucas, Skywalker Sound.

1980 “The Empire Strikes Back” is released.

1981 With his USC film school cohort, Steven Spielberg, Lucas develops “Raiders of the Lost Ark.”

1982 Lucas gets into the gaming business with the debut of Lucasfilm Games, which becomes LucasArts.

1983 “Return of the Jedi” debuts.

1986 Lucas sells Pixar technology to Steve Jobs.

1991 Lucas receives the Irving G. Thalberg Life Achievement Award from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences at the age of 48.

1996 Lucas again builds something where they say he can’t, this time at Big Rock Ranch, down the street from Skywalker.

1999 “Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace” debuts in theaters.

2001 Lucas signs a lease to develop a campus on a 23-acre plot of land in San Francisco’s (former army base) Presidio district.

2002 The THX Group is spun off into a separate company.

2002 “Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones” is released.

2005 “Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith” premieres.

2009 Lucas is inducted into the California Hall of Fame.

2011 Lucas quietly begins to shop Lucasfilm, looking for a corporate home that will protect the company and provide enough resources so it can continue to create. He also decides to build his Grady Ranch facility, going back to the county for final planning approvals.

2011 Grady Ranch neighbors threaten to sue Marin County if they approve the project. When the county blinks, Lucas doesn’t. Instead, he shocks Marin by pulling the plug on the project and turning the property over to the Marin Community Foundation to build affordable housing.

2012 Lucas shocks the entertainment world by selling Lucasfilm to Disney for $4.05 billion.

2013 Disney shuts down LucasArts, displacing hundreds of highly skilled programmers and game developers.

Bill Meagher is a contributing editor at NorthBay biz. He’s an associate editor at The Deal’s West Coast office in Petaluma and is an author. He lives with his wife, Cindy, and cats Riggins and Vince, in San Rafael.