A bright red and white poster at the entrance to Target in Novato reads Help Wanted. Similar signs are popping up in others areas of the North Bay, often staying there for weeks at a time, suggesting that workers at the bottom of the pay scale are reluctant to apply for jobs in areas where they can’t afford to live. It’s one of the problems that results when a living wage—the amount workers have to earn to pay for necessities like housing and food—exceeds the amount they actually earn by a wide margin. The disparity is something the state of California hopes to remedy with a series of increases in the minimum wage. It seems like a simple solution at first glance, but in reality it’s complex, with issues that make the outcome far from a sure thing.

A bright red and white poster at the entrance to Target in Novato reads Help Wanted. Similar signs are popping up in others areas of the North Bay, often staying there for weeks at a time, suggesting that workers at the bottom of the pay scale are reluctant to apply for jobs in areas where they can’t afford to live. It’s one of the problems that results when a living wage—the amount workers have to earn to pay for necessities like housing and food—exceeds the amount they actually earn by a wide margin. The disparity is something the state of California hopes to remedy with a series of increases in the minimum wage. It seems like a simple solution at first glance, but in reality it’s complex, with issues that make the outcome far from a sure thing.

Dr. Robert Eyler, chief economist at the Marin Economic Forum (MEF) and a professor of Economics at Sonoma State University (SSU), explains that a divergence occurs when the minimum wage, which is fixed, doesn’t rise as fast as the cost of living, which is always in flux. “You have some people who get more and more behind the eight ball,” he says, pointing out that when the cost of living goes up rapidly, low-wage earners are marginalized and can’t access health care or proper food. Many depend on food banks to feed their families and, since housing also becomes a challenge, they might share accommodations or combine households. “They have limited upward income ability, so they get deeper and deeper into economic trouble,” he says.

The intent of legislators in approving Senate Bill 3 was to lift the state’s lowest paid workers out of poverty. Governor Jerry Brown signed the bill into law on April 4, 2016, with the first of the incremental increases to occur on January 1, 2017. The bill passed both the State Assembly and the State Senate largely along party lines, with Democrats in favor and Republicans opposed. The North Bay’s representatives in Sacramento—Sen. Mike McGuire (D-Healdsburg), Sen. Lois Wolk (D-Davis), Assemblyman Bill Dodd (D-Napa), Assemblyman Mark Levine (D-San Rafael) and Assembly Jim Wood (D-Healdsburg)—all supported the bill.

poverty. Governor Jerry Brown signed the bill into law on April 4, 2016, with the first of the incremental increases to occur on January 1, 2017. The bill passed both the State Assembly and the State Senate largely along party lines, with Democrats in favor and Republicans opposed. The North Bay’s representatives in Sacramento—Sen. Mike McGuire (D-Healdsburg), Sen. Lois Wolk (D-Davis), Assemblyman Bill Dodd (D-Napa), Assemblyman Mark Levine (D-San Rafael) and Assembly Jim Wood (D-Healdsburg)—all supported the bill.

Before the state took action, however, the Fight for $15 was an ongoing nationwide campaign (that began in 2012) to support fast food and other low-wage workers seeking $15 per hour and a union. “As part of that campaign, local participants in the Fight for $15 led by SEIU and North Bay Jobs with Justice gathered signatures for two different ballot initiatives to raise the minimum wage,” says Martin Bennett, co-chair of North Bay Jobs with Justice and instructor emeritus of American history at Santa Rosa Junior College. Technically retired, he continues to teach part time. “One qualified in March but was removed when a deal was struck with the governor and the legislature in April. Another would have qualified likely in April (it was more comprehensive that the first and also mandated six paid sick days for all covered workers). The second would likely have been the one that would ultimately be on the ballot.

“We collected hundreds of signatures for both in Sonoma County and supported both,” says Bennett, who reports that public opinion was favorable, so he feels it’s likely the initiative will pass.

“It was the statewide grassroots campaign that really brought the pressure on the legislature and the governor to implement a $15 per hour minimum wage and avoid a ballot initiative in the fall,” he explains.

He adds though, that $15 per hour is not a true living wage: According to a report by University of Massachusetts economist Dr. Jeannette Wicks-Lim, a family self-sufficiency or living wage for two parents each working full time to support two children is $22 per hour.

“The state minimum wage will be phased in to reach $15 by 2022,” Bennett points out. “However, numerous California cities have implemented their own citywide minimum wage of $15 per hour that will be phased in more rapidly. In June 2016, 13 cities in Santa Clara County agreed to approve a $15 per hour minimum wage by 2019.” In San Francisco, a city-approved phase-in will reach $15 by 2018, and some cities are forming local coalitions to decide on their own minimum wage. In June 2016, for example, 13 of Santa Clara County’s 15 cities agreed to raise the minimum wage to $15 by 2019.

“It’s a real possibility that cities in the North Bay could implement citywide minimum wage laws with a quicker phase-in than the new state minimum wage,” says Bennett.

Eric Lucan, a member of the Novato City Council and chairman of the Marin County Council of Mayors and Councilmembers’ minimum wage working group, reports that the group began exploring the issue when several neighboring cities began passing local minimum wage ordinances, and it created a white paper to chronicle its findings. “We put together a working group of communities in Marin to explore the issue over the course of a year,” he says. Following the passage and implementation of SB3, the group could still reconvene to analyze its effects. If the group were to consider a countywide minimum wage that’s higher than the state’s mandate, and it would require each participating municipality to pass an ordinance for its jurisdiction. One recommendation the group did decide on was for the jurisdictions in Marin to be in open communication with each other if any decided to move forward with an ordinance. “We don’t want a hodgepodge,” says Lucan.

Real costs

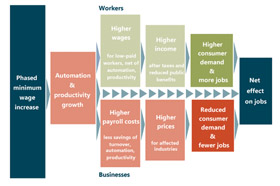

The wage hike is good news for workers, but for employers, it goes beyond a simple increase. In addition to higher wages, they’ll also have to pay more in workers’ compensation insurance and taxes, and may have to pay more for supplies if the businesses they deal with raise prices to compensate for greater costs. In addition, workers slightly above the minimum wage threshold could demand an increase, causing a ripple effect—and while employers aren’t obligated, the demand will be there, which could create a domino effect, says Eyler.

The wage hike is good news for workers, but for employers, it goes beyond a simple increase. In addition to higher wages, they’ll also have to pay more in workers’ compensation insurance and taxes, and may have to pay more for supplies if the businesses they deal with raise prices to compensate for greater costs. In addition, workers slightly above the minimum wage threshold could demand an increase, causing a ripple effect—and while employers aren’t obligated, the demand will be there, which could create a domino effect, says Eyler.

The resulting cost to businesses is one of the major arguments against increasing the minimum wage. The fear for opponents is that employers who face higher expenses will cut jobs, reduce hours or perhaps replace people with technology, leading to higher unemployment. “It will depend on the industry, but the threat is real,” says Eyler, who also points out that while it’s a possibility, it’s not a guaranteed result. “Logic suggests that if you have increased costs, you might let someone go,” he says, but some businesses will raise prices instead. On the flipside, he points out that, if businesses pay more in wages, workers might spend more, thus increasing revenue. “It’s very debatable what the final effects would be,” he says. “It’s a very, very tricky debate.”

Ken Jacobs, chair of the Labor Center at UC Berkeley, thinks it’s unlikely major job losses will occur, because most businesses will be able to absorb the increased costs. He points out that labor is slightly more than 20 percent of total operating costs for most businesses, but not everyone is starting at the bottom and receiving minimum wage; higher-paid employees make up a greater part of the operating budget. In addition, “Part of the cost is absorbed in savings to the firm because of improved performance,” he says, and if employees get adequate compensation, they stay in a job longer, reducing hiring and training time.

He cites a Labor Center study that focused on San Jose and showed that the increase in prices as the result of raising the minimum wage would be 0.3 percent across the economy as a whole and 3.1 percent in restaurants. “This is a very small impact on prices across the entire economy,” he says. “Minimum wage laws have been shown to be an effective way of raising earnings for lower-wage earners,” he observes. “They do what they’re intended to do without negative effects on employment or the economy.”

Mixed results

In Napa County, some businesses have already raised wages voluntarily as a way to attract and retain workers. “A lot of our businesses pay competitive wages,” says Alfredo Pedroza, chairman of the Napa County Board of Supervisors, who serves on the Economic Development Policy Committee of the California State Association of Counties and works in the finance service industry. He explains that many local businesses have to pay above the minimum wage if they want to compete in the labor pool; it’s an example of the free market at work, although it doesn’t apply to everyone. Pedroza suspects the new minimum wage could have an impact on seasonable small businesses, such as flower shops with young adults and seniors as part-time workers, and he speculates that they might shrink their workforces.

He points out that labor is a fixed cost, and when businesses have an increase, they can pass it through to consumers or take it out of profit margins. One of his concerns is that, if businesses raise prices, they risk increasing the cost of living. He gives the example of a sandwich that’s currently $8 and goes up to $8.50. In isolation it’s a small amount, but when all the price hikes add up, they become significant. “You have to take a holistic view. It can be counter to the original purpose,” he says. “You can’t look at wages in a vacuum. If you push up wages, it pushes up the cost of living.” That, in turn, risks negating the purpose of the minimum-wage increase.

He also points out that, while the minimum wage is beneficial for workers, it’s important to be mindful of consumers, such as seniors on a fixed income. “Their income isn’t going up, while the price of a basket of goods goes up,” he says. He believes balancing wages and the cost living is necessary to avoid unintended consequences. On the bright side, he finds it a plus that the minimum wage will go up gradually, so businesses will have time to figure out the best way to phase it in.

He also points out that, while the minimum wage is beneficial for workers, it’s important to be mindful of consumers, such as seniors on a fixed income. “Their income isn’t going up, while the price of a basket of goods goes up,” he says. He believes balancing wages and the cost living is necessary to avoid unintended consequences. On the bright side, he finds it a plus that the minimum wage will go up gradually, so businesses will have time to figure out the best way to phase it in.

Jessica Taylor, Job Link manager with the Sonoma County Human Services Division, reports that her interactions with businesses have been mixed. “I’ve heard from some businesses that increasing the minimum wage does create hardships on them and increases their costs,” she says, but she’s also encountered others actively trying to attract more workers by increasing wages. She believes the North Bay’s high cost of living and resulting lack of access to housing prevents new people from coming into the area, while current residents can’t justify working for low wages. “I think as long as we remain a very expensive place to live, we’re going to have this issue,” she says.

In Marin County, Joanne Webster, president and CEO of the San Rafael Chamber of Commerce reports her organization conducts hundreds of business retention and expansion interviews each year as part of its Economy Vitality Outreach Program, and respondents say that recruiting and retaining employees is difficult because the price of homes and the cost of living are so high. Their tactic has been to offer more than the minimum wage, but even that strategy doesn’t always get the desired results. “I heard from a Marin County bank recently that it held a job fair this past spring for entry-level bank tellers, and only two candidates attended,” she says.

Webster finds that one of the biggest concerns is that employees at a higher level on the pay scale will demand an increase to reflect their experience with the company and differentiate them from workers earning the lower wage. “If a retailer is paying $12 to $15 per hour now, and the minimum wage goes up, then they’ll have to bump up that starting hourly wage for current employees even more,” she says, and that impacts everything. For example, if a coffee shop has increased labor costs, and its suppliers are pushing up their prices to reflect their higher costs, then the shop might have to raise its prices, too.

demand an increase to reflect their experience with the company and differentiate them from workers earning the lower wage. “If a retailer is paying $12 to $15 per hour now, and the minimum wage goes up, then they’ll have to bump up that starting hourly wage for current employees even more,” she says, and that impacts everything. For example, if a coffee shop has increased labor costs, and its suppliers are pushing up their prices to reflect their higher costs, then the shop might have to raise its prices, too.

She observes that the kind of business determines whether or not it can absorb the cost of the increase. “If you’re a small mom-and-pop shop, you might consider working more hours yourself,” she says, so reducing employee hours and not creating new jobs is a real possibility. And it’s not just small businesses that will feel an impact. The increase will have an effect on large retail stores such as Macy’s and Target as well. But Webster expects the biggest impact to be on the hospitality and retail industry.

Complications

When it comes to restaurants— especially fine-dining establishments—the situation gets complicated. “Approximately half of my staff are minimum-wage employees,” says chef Ken Frank, owner of Michelin-starred La Toque in Napa. However, those employees work on the floor and get tips in addition to their base pay; when averaged out, they can make up to $45 per hour. “I pay my employees really well,” he says, and he gives them generous benefits. However, he adds, “Every time you give someone a raise at a lower level, you have to give others a raise, too.”

When it comes to restaurants— especially fine-dining establishments—the situation gets complicated. “Approximately half of my staff are minimum-wage employees,” says chef Ken Frank, owner of Michelin-starred La Toque in Napa. However, those employees work on the floor and get tips in addition to their base pay; when averaged out, they can make up to $45 per hour. “I pay my employees really well,” he says, and he gives them generous benefits. However, he adds, “Every time you give someone a raise at a lower level, you have to give others a raise, too.”

When the minimum wage goes up, everything goes up, and payroll and workers’ comp are already big numbers, so in a traditionally low-margin, high-risk business, “It all gets very expensive,” he says. “The challenge is that they’re pushing us to give raises to people who don’t need it,” and that makes it more difficult for him to give a more meaningful amount to cooks in the kitchen. “It hits restaurants particularly hard, because we’re a labor-intensive industry,” he says.

When the change comes into effect, “We’ll look at how many full-time employees we can afford,” he says, in addition to managing hours carefully and perhaps cutting benefits. He expects others will do the same. He reports that low-end restaurants have already been contemplating automation, and the coming wage increase could make technology an attractive option that would let them cut labor costs. In addition, he predicts prices to consumers will go up. “The money has to come from somewhere,” he says.

Creating further concern, some organizations are lobbying for exemptions based on the number of employees. “That would exempt some of my competitors. It would have exempted the original La Toque in Rutherford,” says Frank.

Instead, he suggests exempting categories of workers, whose salaries are based on minimum wage but earn substantially more, such as servers or bartenders who can get $300 in a night. Because all restaurants are considered equal when it comes to pay, “Fine restaurants are unfairly tarred with the same brush as fast-food restaurants,” he says, and the failure to differentiate between them gives higher-end restaurants a lousy-place-to-work label. Employees don’t plan to make a career in the fast-food industry, whereas they do in fine dining. He believes that should be a consideration that’s reflected in what they earn.

One way to create a fairer system would be to shift to the European model, where costs are included in the price of food and drinks, and restaurant workers receive a solid living wage instead of tips. “In Europe, it’s mandated, and it’s wonderful,” says Frank. “I think it’s a much more civilized way to pay people.” He points out that customers here decide what the service is worth after workers have already done the job, and says, “I think it’s unfair. It’s demeaning. Nobody would ever pay a dentist or a mechanic that way.”

the price of food and drinks, and restaurant workers receive a solid living wage instead of tips. “In Europe, it’s mandated, and it’s wonderful,” says Frank. “I think it’s a much more civilized way to pay people.” He points out that customers here decide what the service is worth after workers have already done the job, and says, “I think it’s unfair. It’s demeaning. Nobody would ever pay a dentist or a mechanic that way.”

It would be a big cultural change, however, and to be successful, all restaurants would have to do it; La Toque couldn’t do it alone. “I don’t want to risk my future, but I personally think it’s the right way to go,” says Frank.

Big picture

“There’s always been this gap between the minimum wage and a living wage,” says UC Berkeley’s Jacobs. He believes real change comes when the minimum wage is closer to the living wage. “Letting the market decide doesn’t work for low-wage employees,” he says. “It’s very expensive being poor.” He uses the example of a worker whose car breaks down: He can’t afford to fix it, can’t get to work and could lose his job. Low wages also have an impact on a worker’s stability and employment, play a role in childhood development, result in lower birth weights and higher infant mortality and affect mental health. “These all have important ramifications,” he says, pointing out that the reduction in absenteeism and better performance will be beneficial to businesses as well as employees.

Jacobs reports that, as an alternative to raising the minimum wage, some economists believe families should get other support, such as universal childcare, paid by the government and taxes.

Eyler suggests a similar solution: “You could tax businesses and redistribute the income to families who are suffering because of the low wage structure.” It’s a strategy that would reach people in need, whereas the minimum wage is across the board and doesn’t differentiate between a struggling 40-year-old mother of three and a 16-year-old in a stable household with a comfortable income. He acknowledges that overtly taxing businesses is a highly debated item, but says, “I’ve heard very few people talking about if the minimum wage will actually exacerbate the local cost of living.”

Eyler suggests a similar solution: “You could tax businesses and redistribute the income to families who are suffering because of the low wage structure.” It’s a strategy that would reach people in need, whereas the minimum wage is across the board and doesn’t differentiate between a struggling 40-year-old mother of three and a 16-year-old in a stable household with a comfortable income. He acknowledges that overtly taxing businesses is a highly debated item, but says, “I’ve heard very few people talking about if the minimum wage will actually exacerbate the local cost of living.”

The piece of the state’s plan likely to be most effective is the indexing that follows the minimum wage increases. “Indexing lets the wage maintain its purchasing power,” says Jacobs, explaining that it’s better for workers and provides more stability for businesses.

Beyond the minimum wage itself, Eyler suggests that people consider the bigger, bolder, social outcome that could result. He believes they’re not thinking about secondary and tertiary issues, such as philanthropy, long-term investments, business retention, economic development and real social outcomes. “We’re going into a grand experiment,” he says. “It’s a very tricky question that all of California has to engage in,” he says. And there are no easy answers.

Looking Back

In 1916, when California’s first mandatory minimum wage came into effect, $0.16 per hour was enough to live on. It was based on the basic budget for a single woman, and the intent was to make sure female workers could support themselves and pay for room, board and other expenses. “It only applied to females, because it was considered that men could fend for themselves in the market. It was based on what the single young woman would need,” says Ken Jacobs of the UC Berkeley Labor Center. The assumption was that older women would be married, not working, and supported by their husbands.

A century later, it’s a different world. It’s the norm for women to work, frequently as sole or equal breadwinners for their families. The minimum wage is $10 per hour and applies to everyone. Even so, it’s not enough. While the cost of living has risen, the minimum wage hasn’t kept pace, so in January 2017, in accordance with California Senate Bill 3, it jumps to $11 and will go up gradually until it reaches $15 in 2022. After that, it will be tied to inflation and indexed to the cost of living, with the Department of Finance calculating the minimum wage for the following calendar year by August 1 annually.

Milestones

1916 $0.16

Nov. 15, 1957 $1.00

Mar. 4, 1974 $2.00

Mar. 1, 1997 $5.00

*Jan. 1, 2016 $10.00

Source: State of California Department of Industrial Relations

*Businesses with fewer than 25 employees start one year later.

Living Wage

Dr. Amy K. Glasmeier at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology has developed a Living Wage Calculator to show the hourly wage an individual must earn to support a family, and she compares that amount to the poverty level and the minimum wage. The following are figures for 2016 for a family of two adults and one child. (Note: It does not include California’s most recent boost in the minimum wage to $10.)

Marin County

Living wage: $29.63

Poverty wage: $10

Minimum wage: $9

Napa County

Living wage: $26.06

Poverty wage: $10

Minimum wage: $9

Sonoma County

Living wage: $25.12

Poverty wage: $10

Minimum wage: $9

Source: Living Wage Calculator, livingwage.mit.edu

County actions

In-Home Supportive Services Workers are independent contractors who are part of state-mandated, county-operated programs that help people with disabilities and low-income older adults stay in their own homes and live independently. An IHSS Public Authority Board in each county acts as the employer of record for caregivers and negotiates wages and benefits on their behalf, as well as screening workers and performing criminal background checks. Workers must register, and the authority also maintains a registry of workers as required by the state.

In Sonoma County, in accordance with a Memorandum of Understanding signed in 2016, pay for IHSS providers will go up to $13 per hour in 2017.

In November 2015, Marin County supervisors approved a cost-of-living increase that will pay workers an estimated $13.30 per hour, making the amount it pays IHSS workers the highest in the state.

In Napa County, IHSS workers receive $12.10 per hour.