David Guhin, Keith Woods and Tennis Wick

Twelve months ago, on October 8, 2017, Sonoma County was on fire and thousands of residents fled their homes in the dark of the night. The Nuns Fire started in Napa and Sonoma counties and burned more than 55,000 acres, becoming the largest Wine Country fire. The Tubbs Fire started near Tubbs Lane in Calistoga and was the most destructive fire in Santa Rosa, resulting in 24 civilian deaths, burning 34,000 acres. Collectively, the Sonoma Complex Fires destroyed 5,300 homes in the area, including Fountaingrove, Coffey Park, and unincorporated areas of Sonoma County such as Larkfield, Mark West Springs, Glen Ellen and a number of rural neighborhoods.

It was an enormous tragedy of unthinkable proportions. The size and scope of the disaster was unprecedented. The task of leading the rebuild effort included three individuals: David Guhin, assistant city manager and director of planning and development; Tennis Wick, director of Permit Sonoma, County of Sonoma; and Keith Woods, chief executive officer, North Coast Builders Exchange.

In the aftermath, out-of-state officials from other communities that had experienced deadly natural disasters reached out to offer support, but none had experienced a tragedy of this size. There was no playbook to follow in rebuilding the community. All normal organization systems and structures were scrapped. Sonoma County’s loss left city and county leaders with the most challenging task of their careers. The three men were asked by city and county officials to be bold, get creative and move forward. Editor Karen Hart met with them to discuss what’s happening now and what residents can expect in the months ahead.

It’s been a year since the October 2017 firestorm. Where are we now?

KW: [Progress] was flat for months and months because people hadn’t settled with their insurance companies. Fire victims hadn’t hired architects or contractors because they didn’t know what they had to spend. They were undecided. The first five to six months there was limited activity. Now there’s a spike, and it’s dramatically different. The pace of rebuilding is accelerated and there’s more activity, particularly in Coffey Park.

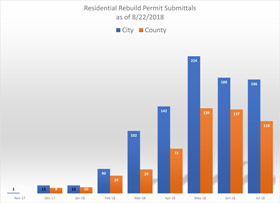

TW: We’ve restored 100,000 acres, protected our watersheds and water sources for 600,000 people. We’ve also cleared 5,300 lots, and currently 25 percent of the 5,300 homes have been designed, permitted and are under construction.

DG: This has been an unprecedented year with the city and county working together to pull this off. Both together and as individual jurisdictions, we’ve found a new way to do business and new ways to partner. Everything from how we are structured to review plans, the policies we put in place, changes to ordinances and the tools developed for the public based on input and need by the homeowner, have set the stage for how we got to where we are. Some of the tools the city has developed over the past few months include real time tracking and web maps that have a tremendous amount of data and information needed during the rebuild process. It’s critical to get information to homeowners as quickly as possible in the most efficient and effective way. At the end of August, more than 1,100 permits were submitted to rebuild homes in the City of Santa Rosa alone. They are now in the process of plan review, construction, or they’re complete and occupied.

What are some of the challenges you’ve faced in the last year?

TW: We’ve been criticized for re-permitting homes in a fire zone, but it’s incumbent on us to be vigilant on [fire zone] areas and how they’re changing and intensifying, but we must also acknowledge property rights. And we need to grow and not think there’s a simple answer as to how complex problems go away. We’ve also had trouble getting geotechnical engineers. [In August,] I met with 56 homeowners who lost their houses that were set on a fault line and/or below a landslide. You can’t have [a tech engineer] come in from Utah and understand our technical setting. We’ve experienced raw anger and frustration [from homeowners], but after a half hour we came up with a solution. It doesn’t fit comfortably; we’re still working on it. But it will involve the Engineering Contractors’ Association and our staff has stepped out of their regulatory role, so we can keep costs down and help people rebuild. From a business perspective, this will extend for multiple years.

DG: Every aspect of the rebuild from design services to permit review staff to contractors are in high demand. We’ve maxed our local workforce and now have support for all aspects of the rebuild coming in from as far away as Hawaii and India.

KW: Preconstruction work, which can be time-consuming and complex, has been slowed down because of the shortage of design professionals as well general and sub-contractors and their workers. As permitting activity increases in 2019, it will tax the building industry’s capabilities and availability even more.

Insurance companies are paying policyholders temporary housing costs for two years. That ends in 2019. Are you concerned about getting enough homes built within that timeframe?

DG: Although we have more than 1,000 homes in the process of review or construction in the City of Santa Rosa in August, it’s only one-third of the homes that were lost in Santa Rosa. We are aware of the situation many are in with their insurance and must do everything we can to help individuals through the rebuild process and make it as streamlined as possible. In addition, we also know that some individuals and families have decided not to rebuild. To that end, we’ve taken an aggressive approach to create new homes and options for our community in Santa Rosa, specifically near transit and in the downtown core.

KW: Getting most fire victims back in their homes within two years will be a real challenge, but the industry is committed to doing the best it can. Many of us were caught off-guard about how long insurance claim settlements are taking, but it’s a reality we have to deal with.

Some residents are choosing not to rebuild. Are you concerned about the impact this will have on Sonoma County?

KW: Yes, I’m concerned. There are hundreds of people who have good reasons not to rebuild—retirements, plans to move anyway, impatience with how long it will take to rebuild. I don’t like the thought of a significant outmigration of workers from all segments of the economy, people that we can’t afford to lose. A lot of properties are being put up for sale and that saddens me.

DG: The loss of our community is a big concern. We’re seeing the impact in the reduced enrollment in our schools, loss of workforce for our local businesses and the loss of our neighbors. We also see many people have been displaced that were not directly affected by the fire, but were renters in other parts of town. This is another reason why we need to find creative and innovative ways to bring new housing of all affordability levels to our community as quickly as possible.

The goal is to bring in 30,000 homes by 2023. What efforts are currently underway to accomplish this and to generate affordable housing?

KW: When people hear 30,000 new homes, they think we’re talking about traditional homes. The verbiage needs to be dwelling units—that means lofts, condos, duplexes, tri-plexes, Accessory Dwelling Units, and even high rises. Also, can we just acknowledge that there’s no such thing as affordable housing here? There’s no free money out there where people can buy a $700,000 home for $200,000. That’s not what exists, nor is it going to be an option. What we’re really talking about is subsidized housing. The only way we’ll see lower prices on existing homes is if there’s a massive downturn in the economy as there was in the late 2000s and the market was flooded with foreclosures. Nobody wants that to happen again.

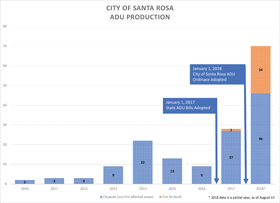

DG: The city and the county have been working closely together over the past six months to take an innovative regional approach to the housing crisis. Both the city council and the board of supervisors have given the direction to create a Renewal Enterprise District with the goal of leveraging and pooling funding to prioritize and support the development of affordable, climate smart, transit-oriented infill projects. In addition, the city is putting a housing bond on the November ballot that will support the development of affordable and workforce housing. Both the city and county are encouraging second units, and the new policies and fee reductions put in place have resulted in a dramatic increase in Accessory Dwelling Units being constructed.

We also want to bring higher density housing of all types to our downtown core. This means we need to go up. We are actively undergoing an update to our Downtown Specific Plan to increase the allowable height in the downtown core near transit. The process will include a full public discussion and through that process will need to acknowledge and address the interaction of higher densities in the downtown core with our historic neighborhoods and how we think parking solutions and encourage alternative modes of transportation.

TW: Since January, we have 16,000 units in the pipeline countywide. This number shouldn’t be surprising if we look around the community. For example, there are hundreds of apartments going in at the Highway 101/116 interchange. And even smaller communities like Cotati and Cloverdale are doing their share.

How many applications in the pipeline result in new housing units?

How many applications in the pipeline result in new housing units?

TW: Most applications that go through the process, make it through approval. Whether they’re built, depends on other factors.

KW: One of those factors Tennis refers to is that some projects ultimately don’t pencil out and can’t get funding. For those who are financing it, if it doesn’t make economic sense, it won’t get built.

TW: It’s a dichotomy. We all embrace city-centered growth, transit-oriented development and focusing around the Sonoma-Marin Area Rail Transit (SMART). That [type of] development at densities approved require structural parking, which adds to the cost of construction. We’re trying to entice people to consider higher levels of development. In the meantime, you see projects going in, but they rely on surface parking.

What’s the City of Santa Rosa doing to help developers?

DG: We’re taking a comprehensive approach to solving the puzzle of making high- density, multifamily housing in our downtown a reality. That includes changing policies to make more housing by right, streamlining the review process and putting resources into an expedited permitting process, reducing impact fees to encourage additional height, taking a creative approach to parking by reducing the requirements and encouraging de-bundling of parking from units and use of car share and other public transportation options.

We’re also looking at all of our public assets in the downtown, including parking lots and garages where we could generate housing in conjunction with the existing parking. The city council has made bringing housing of affordability levels to our downtown and to do that we need to be partners with those looking to build quality projects and use our tools to encourage creative, transit oriented and climate-smart projects that we can be proud of as a community.

You were tasked to “get creative” with the rebuild. What types of creative housing projects are you looking at?

You were tasked to “get creative” with the rebuild. What types of creative housing projects are you looking at?

DG: Creativity and urgency have been two key elements of the rebuild. This includes policies such as the Resilient City Ordinance that the council adopted just a month after the fires to help with the rebuild, creative staffing approaches and the use of electronic plan checks, and being okay with making changes and determinations on the fly to accommodate unprecedented situation in an unprecedented time. We’re also seeing creative housing products come through on the rebuild, including a few different net-zero energy designs, alternative building materials and an increase in second units.

TW: Currently, we’re working on cottage developments—an idea that’s working in Portland. Consider a 5,000-square-foot lot to which one can apply setbacks, height, and lot coverage rules to end up with a 2,400-square-foot house. Homes of this size in Portland’s economy—as well as our own—aren’t affordable. A cottage development allows an owner to take that same 2,400-square-foot house and build up to three units of varying size, depending on market needs. For example, you could build two 1,200 square-foot homes, or a 1,200/800/400 square-foot combination. It’s the same three-dimensional volume as the 2,400-square-foot house and you get smaller units that are more affordable by design, instead of a public subsidy. Design review will ensure that projects happen in a tasteful manner and respects community character. Look around older neighborhoods and you’ll find examples of this type of construction that fit right in established neighborhoods where property values are high. The planning commission and board of supervisors are considering this program, and other housing legislation now.

KW: There is an existing local example of what Tennis is describing: Oakmont. It works and it’s aesthetically pleasing and functional. In a way, the devastating fires have led us to enter a new era of creative approaches to housing. Everything is on the table. In Vancouver, they’re adding ADUs and in some cases are at the end of “pathways” – which we call driveways. This maximizes properties and the houses on them. This is done rather than building out into the countryside, which few people in Sonoma County want to see happen. The second benefit of ADUs is that people generate income while providing a small housing unit for someone.

Some large employers are concerned about housing issues to retain talent in the area and recruit skilled professionals to the area. How is this currently being addressed? Specifically, how is the city trying to keep people in the area?

DG: As the mayor said from day one, “We need to walk and chew gum at the same time to get through this and not end up—three years from now—at the same place we were in 2017. That means, while the city and county are taking an unprecedented approach to rebuilding and getting people back into their homes as fast as possible, we must be creating new and creative housing that our employers and community need at the same time. We have had an overwhelming demand for downtown housing from large and small employers, including those in technology, the medical industry and those in the educational field. The demand in Santa Rosa has never been higher for transit-oriented development near the center of the downtown where people can live near where they work, walk to restaurants, bars and other services and take advantage of the amenities of living in an urban setting. We know this is a key element in supporting our employers and community at large, and we’re pulling out all the stops to see this become a reality.

How do you feel about the progress on this massive rebuild project one year later?

KW: The only silver lining of the horrendous fires is that it’s taken off the handcuffs and we’re getting creative, both in permitting and building. It’s time to design a new community. I’m glad that we’re now moving at a quicker rebuilding pace than many experts predicted.

TW:I feel really hopeful about what we’ve done and talked about as a community. That’s extraordinary.

DG: We’re more than a third of the way in rebuilding homes lost in the fire, and that brings hope and encouragement that we can and will [recover] from this. But at the same time, we have a long way to go. We have people in our community that are still working through debris issues, insurance issues, displacement and those that are underinsured and need assistance to get back into a permanent home. In addition, we need to rebuild our municipal infrastructure that was damaged and work with FEMA and CalOES to make sure we can bring as much funding as possible to our community to help make sure we come back even more resilient than before. Our community has shown over and over since last October that we’re in this together and have proven that residents, nonprofits, faith-based organizations and the government at all levels can come together. And that is inspiring.

What’s R1 Zoning?

The term R1 zoning typically refers to a piece of real estate located in a neighborhood of single-family residences. Most local laws restrict R1 zoning to one freestanding house, intended as a dwelling place for one family.

Housing Terms

Accessory Dwelling Unit (ADU): An ADU is a backyard cottage, which can be up to 1,200 square feet, and is a small permanent home that may be established in addition to the main dwelling on a parcel zoned for residential use. Most residential zoning districts allow one ADU unless there is a “Z,” an ADU exclusion overlay zoning on the property. ADUs can be rented for long-term occupancy, but they can’t be used as vacation rentals.

Junior Accessory Dwelling Unit (JADU): A JADU is a smaller living unit (up to 500 square feet), created out of a bedroom within an existing family home. It’s created by adding an efficiency kitchen and an exterior door to an existing, legal bedroom. It may include a bathroom with the house. JADUs are allowed in every zoning district that allows a single-family dwelling. It can be rented for long-term occupancy, but can’t be used as a vacation rental.

For more information, visit www.sonomacounty.ca.gov.

Housing Bond

In November, Santa Rosa voters will decide whether they want to support a $124 million housing bond to increase the supply of affordable housing. They’ll also be asked to pass a quarter-cent sales increase for six years that would raise $9 million to help close a city budget gap, which was caused in large part by costs resulting from the 2017 October firestorm.