Picture this: You arrive at your home after a hard day at work. You gather your things, get out of the car and watch it drive off—by itself. It navigates solo to a lot somewhere on the outskirts of town, parks and waits for morning, leaving you with a clear street and, if you have one, lots of space in your garage. Futuristic fantasy? To practical techies in Silicon Valley and automotive makers worldwide, the answer is no, not at all.

Johann Jungwirth, former Apple executive and chief digital officer at the Volkswagen Group, told an audience at the Geneva Motor Show in 2016 that the auto industry was “reinventing mobility.” Driverless cars, he suggested, will improve our quality of life, giving back hours of time we currently waste in traffic so we can spend quality time working, talking with each other and being productive. Is that a dream? Maybe. But the self-driving car, which for most of us is still a vague idea too far away to be excited or worried about, is coming to a neighborhood near you—not tomorrow, but possibly, if you listen to Jungwirth, as soon as 2025. So what exactly should we expect?

Degrees of Automation

The degree of automation, as recognized by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, will range from Level Zero to Level Five. The fully automated Level Five car will have an automated driving system (ADS) and will do all the driving in all circumstances. The people on board a Level Five car are passengers and never involved in driving. This degree of autonomy, for now, is extremely expensive, with high-tech infrastructure including radar and LIDAR (Light detection and ranging) with connections to constantly updated cloud and 3-D mapping providers. This fully automated car will take the most time to perfect.

The Level Four car has a high degree of automation with an ADS that can perform all driving tasks on its own, including monitoring the road in certain circumstances. The Level Three car has an ADS, and it controls all monitoring of the environment. It performs all driving tasks under some circumstances. Still, the human must be ready to take the wheel. The Level Two car has what is called an advanced driver assistance system (ADAS), which can control steering and braking and accelerating under some circumstances. The human driver must pay attention to all other driving tasks. Level Zero will leave all the driving to the human, which is where many are at present most comfortable.

(An MIT SAIL self-driving vehical prototype ) -Courtesy of MIT

The History of Transportation

Looking back to 19th century urban America, the horse and carriage, romantic as it may seem, had its drawbacks as the primary means of transportation. Horses had to be fed and housed – and often were not; they had to be treated humanely – and often were not; they hauled their cargo, both human and freight, but dropped loads of manure daily on city streets, a feature which associated them with filth and disease. Worse, due to starvation and abuse, horses also dropped dead in the streets, causing traffic jams. The “horseless carriage,” even with its toxic exhaust, offered relief and a new form of transport for those who could afford it. But transition did not happen smoothly. Roads had to be paved. Rules of the road had to be created to avoid chaos in the streets. Businesses associated with horses and carriages were phased out and farmers suffered as the price of grain crashed. When cars stalled on the roadsides, skeptics hollered, “get a horse!”

To the doubters, Thomas Edison, who revolutionized the way we lived through his inventions such as the light bulb, the phonograph and the movie camera, saw the coming of the horseless carriage as inevitable progress. In 1895, he said, “You must remember that every invention of this kind adds to the general wealth by introducing a new system of greater economy of force. A great invention which facilitates commerce enriches a country just as much as the discovery of vast hordes of gold.” So, no doubt, the self-driving car is on its way. How, and when, will it enrich our daily lives?

(Jim Dadaos,Tri-Star Automotive)

Bracing for change

Jim Dadaos has been in the car repair business for more than 30 years, working on glamorous and cantankerous cars such as MGBs, Jaguars and Aston Martins, as well as Fords, Chevys and Hondas. Many of his cars are classics, and his customers are treated as such, too. “Most of our customers are long term,” he says, adding that some of them came in first with their parents, as babies, and now are coming in with babies of their own. “One customer recently said, ‘I’ve had Jim longer than I’ve had my hairdresser and I will never let my hairdresser go!’” He says that because cars are always evolving, Dadaos’ shop, Tri-Star Automotive in Santa Rosa, has to stay up-to-date on all of them. But new cars, equipped with highly sophisticated electronics, will have a few years under warranty before he’s ready to work on them, other than basic maintenance.

But a 2017 study by IHS Markit states car owners are holding onto their vehicles for longer than ever. With plenty of work available for Dadaos, regardless of technology, the notion of self-driving cars appearing in the next five years fills him with neither dread nor joy. “I’m not wild about them, to be honest,” he says. “I’m just not sure the technology’s there. I read about them. You read Elon Musk and the Tesla is not completely driverless. I assume we’re going to get to the point when the technology is there, but I don’t know at what point we’re all going to agree and say, ‘Yes, it’s there.’”

Dadaos was in Arizona last spring when a highly reported accident happened. “There were all these Volvos driving around with things on the roof, and we asked, ‘What’s that?’” Turns out they were Uber driverless cars. “We were there when one of them ran over someone on a crosswalk,” Dadaos reflected. Uber, a pioneer of self-driving cars, published a statement on its website after the accident, informing readers they’d withdraw prototype vehicles from road testing until a top-to-bottom review of their safety approach, system development and culture was completed. The statement said the company would take “A measured, phased approach to returning to on-road testing.”

There are tragic accidents now, of course, with regular cars and drivers who don’t pay attention, and maybe the automated car could become safer than distracted human drivers. Still, there needs to be some criteria, and a record over time for Dadaos to feel comfortable with the new technology. “I would have to see a couple of years of crash-free, trouble-free driverless vehicles,” he says. “Or maybe a year’s worth.” He acknowledges that with continued testing, the engineers and designers will likely succeed. “I know there are a lot of bright people working on these systems, so they must be on the right track. As technology gets better, it’s going to be safe. But how bad is it to be on the road and be in control of your car? I don’t have a problem with that.”

The Insurance Issue

Robb Daer, chief operation officer at George Petersen Insurance Agency, admits the driverless cars are going to be a big thing in our lifetime, but is he going to get one? “I don’t think so,” he laughs. “I like driving.” We turned to Daer to see if, in his opinion, any surprising insurance complexities might arise when drivers have to contend with autonomous cars, and vice versa. He says the field is too new to see any specific changes on the insurance horizon. Large companies like Uber can self-insure if they want to, but the principle of insurance—paying to be prepared to cover any costs of an accident—will remain. He does allow that, due to the huge expense of these autonomous cars, costs for coverage might increase. Imagining the future, a funny thought occurs to him. “You remember back in the ‘90s when everyone was freaked out about computers not turning over to the year 2000? Insurance carriers were putting “Y2K” exclusions into their policies in case they ended up with claims from computers blowing up?” He laughs, recalling that the twenty-first century arrived without the dreaded glitches and life went on. Maybe so with self-driving cars? “It’s definitely going to be a bigger thing in our lifetime,” he says.

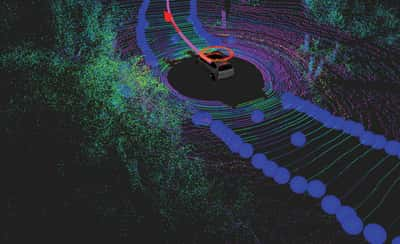

(Digitial imagery from the MIT Maplight program)

Who Benefits First

Who are you likely to see riding around in an autonomous car first? It could be businesses that benefit before you or your neighbors do. Think of the Wine Country tour busses, large and small, that drive about, transporting tasters safely and reducing the number of cars on roads and in wineries’ lots. Wouldn’t a Wine Country touring service love to have a self-driving car?

Sonoma resident Bill Boerum, who’s been in the business for 12 years, and his company, California Wine Services LLC, offers its own custom, personalized tours to people who come from all over the world to see Wine Country. He picks guests up at the airport, drives them to the famous, the boutique and the out-of-the-way wineries in Sonoma and Napa counties and gives them an education on what they’re seeing on the way. One could imagine him sitting with his international guests, in his autonomous van, thoroughly engaged in conversation, as the car did the driving. Wouldn’t he love it?

The answer is no, not yet. “Many people are going not just to wineries on Highway 29 or Silverado Trail, but up in the mountains, or even on the valley floor, on very twisty, curvy roads,” he says. “Many of these areas have no service. In some places it’s spotty service. So from a wine visitor standpoint, there’s a challenge—both in the ability of the car to stay on the road, to get to places, to maintain the signal, to be safe and to get around.” This is a significant concern and illuminates those “certain conditions” that Level Three and Level Four cars are limited by.

And of course, the techs are working on it. In 2018, a team from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) were tasked with the problem of getting cars to navigate on unfamiliar and unmarked roads. They developed MapLite—this uses sophisticated onboard sensors such as cameras, LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging), GPS (Global Positioning System) and IMU (Inertial Measurement Unit) instead of predetermined maps to enable the car to determine the shape of the road and to plot a safe path along it. How soon will cars in showrooms have the MapLite capability? “Currently, MapLite is a research project at our lab in CSAIL and we have no immediate plans to commercialize it ourselves,” says MIT robotics researcher Teddy Ort. “However, we do work closely with our sponsor, the Toyota Research Institute as they develop products for real-world deployment.” He allows that currently, the expense for a vehicle empowered with LIDAR would be prohibitively expensive—around $75,000 additional, per vehicle. However, he says, “Some LIDAR manufacturers have predicted the prices falling to as low as a $100 per vehicle in the next few years, and therefore I don’t believe the additional cost to outfit a vehicle for self-driving will be prohibitive.” With any such reduction in price, the timeline for the appearance of self-driving cars would shorten drastically.

They’re getting closer to that ideal, but Boerum’s reservations will remain until the technology further evolves. Yet this is not a problem for him or his guests. He loves to drive and they feel secure in his experience. He particularly enjoys educating his guests who are new to the valley. So, we persist, wouldn’t that experience be even better if he could sit facing them while the car drove itself? “If you had a driverless car, you’d have a chance for eye contact,” he admits. “It would be more interactive. So the tour guide would be more engaged with the passengers.” That will be nice, true. But meanwhile, he’s happy to drive.

(Teddy Ort, MIT Robotics researcher)

What do auto manufactures offer now?

The Germans plan to call it the BUZZ, which we may pronounce, with familiarity, the “bus.” Volkswagen’s futuristic design, which is still on the drawing board, is reminiscent of the much-loved hippie bus of the ‘70s, designed to be a fully electric 369-horsepower transport that can leap from zero to 60 mph in 5 seconds with an expected 270-mile range per charge. The prototype looks a lot like the original microbus, but with significant changes. As an all-electric car, it has no internal combustion engine and thus no grill, and all the lines are smoothed out. Inside, eight seats can be folded and rearranged for a lounge effect—great when the car is in fully automatic mode and you and your friends can sit back and talk while the BUZZ takes you there. Meanwhile, the design allows for inductive, or wireless, charging, and sensors for autonomous driving are on the top. Designed to appeal to an American market, this fully electric bus is not in showrooms now, but we can hope to see them in the next couple of years.

The fully autonomous, Level Five version will take longer to produce, but promotion literature indicates a tentative target goal of 2025. Connor Mysliviec, a sales associate at Hansel Volkswagen in Santa Rosa and recent graduate of Sonoma State University, did a 30-page audit of the Volkswagen Group for his senior thesis. A VW lover since his first car at age 16, he is excited by Volkswagen’s plans for the future. For him, the big, impressive leap is not so much about the autonomous car, but the all-electric vehicle. “People are more concerned with the all-electric idea and the coolness of the bus,” he says. As for the autonomous version, “They’re taking it slow.” Ideally, at some point, the drive for an all-eclectic vehicle and self-driving cars will overlap.

On the horizon

Love them or hate them, autonomous cars are coming. They may make transportation safer, taking the wheel from distraction-prone humans. They may save our environment, as they’ll be mostly, if not all, electric and emission-free. The lifestyle shift could be drastic, but the results could benefit society in ways we’ve yet to consider.

“I’m not a prophet,” says Ort. “But I think the world will be not only safer, but more accessible as well. People often focus on the thousands of lives lost every day in motor vehicle accidents as the primary benefit of introducing autonomous vehicles, and I completely agree that reducing accidents, by any amount, is an important goal.

“However, I also think about the millions of people today who find their mobility restricted because they are disabled, or too old, or simply too poor to be able to drive themselves. Autonomous mobility promises to give disabled people back the freedom to visit their families without relying on someone else. It can help people obtain their medications, or run their daily errands without even needing to leave their home. I believe this ability to bring things from point A to point B without requiring a human escort will drastically improve the accessibility people have to the things that are important to them in a very positive way.”