One of the oldest wineries along West Dry Creek Road in Sonoma County is A. Rafanelli Winery. Nestled on a knoll that offers a sweeping view of the valley, the rustic winery is still family-owned and operated. And though it operates by appointment-only reservations and there’s a gate at the bottom of a hill that requires a code, it has remained true to its family traditions and heritage. Wines are still produced in the same old-world style, tastings are held in the barrel room, a chalkboard on the wall lists wine for sale, and chances are someone from the Rafanelli family is on hand, hosting visitors.

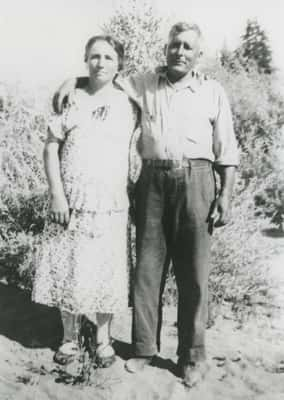

A fourth-generation business, the Rafanelli story began more than a century ago when two Italian immigrants, Alberto and Letizia Rafanelli, settled in Healdsburg to begin a new life. Today, the winery is known for its acclaimed, award-winning Zinfandel and Cabernet Sauvignon. And though the wine label prominently features Alberto’s first initial, what’s not so well known is that it was Letizia who was born into a winemaking family and instrumental in starting the business.

The land of opportunity

As the story is told in family lore, Letizia Tonneti was born in 1882 in Orentano, Italy, about 15 miles from Lucca. She grew up in the business, learning to prune the vineyards as a young girl. “She finished her schooling in Florence and returned home and asked her family what her position would be under the Tonneti label and was told they’d ‘find her a nice mate,’” says David Rafanelli, Letizia’s grandson.

As the daughter of a wine-making family, Letizia knew there was no future for her in Italy and boarded a ship in 1903 to come to America. She was 19 years old, and a brother accompanied her on the journey. They arrived in Ellis Island, and then traveled to San Francisco by rail. “It was probably in the back of a box car,” says David. When they reached the west coast, her brother helped her get situated and made certain she had a small pearl-handled pistol for protection, then returned to the family farm, according to an account written in Healdsburg’s Immigrants, an anthology by Shonnie Brown, in a chapter written by Norma Rafanelli with her nephew, David.

Despite her Italian heritage, Letizia was a blue-eyed blonde and a diminutive figure at five-foot-two, weighing only 90 pounds. She found work in a cigar factory and carried the pistol in her purse.

Alberto was from Elba, Italy, and also dreamed of a better future. His father was a shoemaker by trade and the family was poor. Young Alberto had completed five years of school when he entered the trades at age 13 to develop carpentry skills. He joined the Italian navy at 17, and in 1903, the same year Letizia arrived in America, he deserted the Navy by jumping ship in Norfolk, Virginia. “He never told me directly why he joined the Italian Navy or why he jumped ship, but I know how important it was to him to have a better life than the one that he envisioned for himself in Italy,” Norma wrote in the anthology. He found work as a carpenter in Boston, then moved to Philadelphia, before settling in San Francisco.

In 1905, Letizia was living alone and still working at the factory when she met Alberto in North Beach. “We believe they met through friends,” says David, but no one recalls the details of their first encounter. They married in San Francisco and began their life together. Then in the early morning hours of April 18, 1906, they awakened to an earthquake that would devastate the city.

Alberto went to work on the restoration of the Fairmont Hotel. “It took a hundred lay carpenters to rebuild the Fairmont and it took three to four years to reconstruct, so he had a good start,” says David. Alberto built a home for them near California Street, using scraps of wood from the hotel.

Trips to Dry Creek Valley

The young couple began making trips to Sonoma County, purchasing grapes from Dry Creek Valley, so Letizia could make wine at home. “The Italians would take wagon trips and Model Ts from San Francisco to Healdsburg to learn more about the area, and that’s how she became interested in buying property here,” says David. She was drawn to the area because it was so much like the wine-growing region in Italy.

“When she and my father took a ride to Sonoma County, Mom immediately fell in love with the vineyards,” Norma wrote. “[She] was definitely the driving force behind their move to Healdsburg.” At the time, their young family included sons Vince who was about 8, and Americo, a toddler. They arrived in 1919 and a rented a home on Ward Street in an area known as little Italy. “They didn’t know a soul when they arrived,” Norma wrote.

“When she and my father took a ride to Sonoma County, Mom immediately fell in love with the vineyards,” Norma wrote. “[She] was definitely the driving force behind their move to Healdsburg.” At the time, their young family included sons Vince who was about 8, and Americo, a toddler. They arrived in 1919 and a rented a home on Ward Street in an area known as little Italy. “They didn’t know a soul when they arrived,” Norma wrote.

After the move, Alberto found work, building houses and became well known in the carpentry trade. Gradually, they began to acquire property. Their first purchase was near Passalacqua ranch, but there was no water on the property and it would cost too much to drill for it. “…they got rid of that land pretty fast,” Norma wrote.

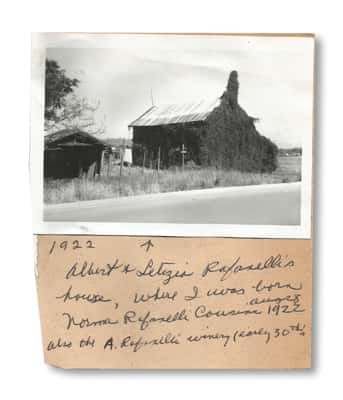

Their next purchase was a parcel of land the family refers to as the “University extension,” that included an old barn covered in thick vines. Alberto converted it into four rooms—three bedrooms with a large kitchen and a winery in the back part. The property featured a partial vineyard, mostly planted with Zinfandel, which had to be replanted, as well as prunes and two acres of Gravenstein apples. In 1922, their daughter, Norma was born there.

Alberto continued his carpentry work, but it was Letizia who worked the land, gradually involving him in farming practices. Along the way, they acquired two horses, Jenny and Bell, and two mules, Tom and Jerry, as well as chickens, rabbits, ducks and turkeys. Letizia spent much of her time outdoors, where she preferred to be, and since the hired help didn’t meet her expectations she did most of the farm work herself, according to Norma’s account. “[She] was the one who planted the entire twelve to fifteen acres of vineyards and tended the grapes.”

It’s no family secret that Alberto wasn’t a natural at farming. “My grandfather wasn’t a farmer. He didn’t get along with the horses and mules,” says David with a smile, recalling that his grandmother described the mules as “temperamental.” One day Alberto was plowing the field with the mules when a car backfired and scared one so badly that it dragged Alberto quite a distance. “Luckily, the earth was soft, so he only got nicks and scratches. Boy, did he sell those mules fast!” Norma wrote.

As Alberto focused on his carpentry work, Letizia handled the day-to-day operations of the farm. “[She] did most of the pruning, planting and picking and taught Dad how to make brandy, sherries and ports—and he became very good at it,” Norma wrote.

The Prohibition era

Prohibition began on January 17, 1920, but Letizia and Alberto were unconcerned about the constitutional ban and began planting winegrapes. “…Mom thought it was a crazy law and would never last,” Norma wrote.

“She knew Prohibition would end, but didn’t think it would take nearly 14 years,” says David. Alberto built a concealed compartment in a pantry in the kitchen, and they continued to operate in secret. “She’d run the still to the secret pantry and pour cooked wine into the septic.”

The family made it through that era with Alberto’s carpentry income and by selling grapes. According to Norma’s account, the family hauled most of the fruit down to San Francisco where they could get $75 [to] $82 a ton, compared to $15 a ton in Sonoma County. Meanwhile, they sold sherry, brandy and grappa on the black market. “Everyone said they had a permit to make wine through the church, but they were selling it out the back door,” says David. “The feds couldn’t stop you from crushing grapes for juice. So [the law] was difficult to enforce, which is why the amendment was changed. A lot of wineries did well by selling grapes to friends one ton at a time.”

As Norma wrote, “The government allowed each family to make two hundred gallons of wine per year for family use. My dad sold gallons and quarts. He bootlegged pints of brandy, and his first winery in the back room of the barn helped us make it through the Great Depression.” According to Norma, Alberto’s situation during that era was unique. “…he had a deal going with the Feds, who chose to close their eyes and ears because they preferred his wines and brandy to all others,” she wrote. “Dad always served them two or three drinks before they bought anything. Then Mom would serve them walnut biscotti so they had some food in their stomachs. Mom would say, ‘We’re not stealin’ or killin,’ just trying to get ahead in life.’”

In 1921, they purchased property on Powell Avenue in Healdsburg, planning to build a home there one day. Alberto and Letizia continued to farm and grow grapes. “She did all the planting, and we lived on vegetables, chickens, eggs and pasta,” Norma wrote. “We were quite self-sufficient during the Great Depression (1929-1942). We had to make do, but we were always happy.”

Prohibition finally ended on December 5, 1933. That same year, Alberto applied for a wholesale winery license and began selling Chablis and Claret by the barrel to restaurants, and A. Rafanelli Winery was stenciled on each barrel. Wine was also sold by the gallon in unmarked jugs to individual patrons.

A few years later, Alberto began work on a house on the Powell property. It cost $4,000 to build and furnish. Most of the materials for the house were purchased in town and the furniture was ordered from Montgomery Ward. Meanwhile, A. Rafanelli Winery was just beginning and of their three children, Americo was showing interest in the family business.

The family remained in the barn until moving to Powell Avenue in 1936, when Norma started high school because Vince and Americo didn’t want their sister living in a barn. In the years that followed, Americo continued to purchase other property, including the Plaza Theatre on West Street (now Healdsburg Ave.), then the local newspaper, and a bookstore, but eventually Americo would focus solely on winegrapes.

He married a young woman, Mary Buchignani, and they had two children—Deanna who was born in 1944 and David, who was born in 1949. In 1951, she succumbed to polio and died. For a time, Americo and the children moved home, and his parents helped raise his young family. Eventually, he remarried a young woman he met while hauling grapes to the daughter of a long-time San Francisco customer. Her name was Mary Longo, and they had one son together, Doug.

During the ’50s, Letizia received legal papers from her family. “They didn’t want her to claim any of the Tonneti estate,” David recalls. “Her parents were getting older, and her brothers were concerned she’d come back and feel entitled. She never signed the papers. She said, ‘I have no intention of going back,’ and she didn’t want to give them the satisfaction. She never discussed it much, but we all knew.” True to her word, Letizia never returned to Italy.

West Dry Creek

In 1955, Americo purchased the Foppiano Ranch on West Dry Creek in Healdsburg, which was mostly planted with grapevines and fruit trees. Meanwhile, he continued to farm the University property.

Young David was showing an aptitude for the business. Farming was in his blood. Some of his earliest memories were of helping his grandfather, Alberto. “I’d follow him on his tractor, with my dog, Toby. We’d run behind him in the furrows,” David recalls. In 1960, when winegrapes were beginning to make a comeback, Americo planted Zinfandel and David helped. “After Pop bought the Foppiano Ranch, he turned it over to Vince and Americo, but we all knew that Americo was going to be the farmer,” Norma wrote.

Vince eventually left the family farm and pursued a career in real estate. Norma married Robert Cousins, and though they never had children together, she helped raise David and Deanna during their childhood. She was an avid golfer and volunteered at Healdsburg Hospital. The properties were run as a family business, but eventually Americo bought out the business from his siblings since they had no interest in running the farm.

A passion for farming

Though David had a passion for farming, his father and stepmother discouraged him from getting into the business. He attended Oregon State University on a partial scholarship for football. “I wanted to major in ag,” says David. “But Mary advised me to get a white-collar job.”

He graduated from college in 1971 with a degree in crop science, and went on to earn a master’s degree in viticulture in 1973 from the University of California, Davis. That same year, they had the first wine label designed for A. Rafanelli Winery, but Americo advised David to get a job because he couldn’t pay him, so he applied for a position at Lambert Bridge Winery, where he worked for the next 15 years.

Along the way, David married Patty Presley and they had three daughters, Rashell, Stacy and Victoria. Like their father, the girls grew up in the family business. During most of the ’70s and ‘80s, David was instrumental in helping his father and Lambert Bridge get their businesses off the ground. The family lived at the Lambert Bridge property, and the girls often brought their father dinner in a red wagon during harvest season, and sometimes they set up a lemonade stand on the side of the road. In the decade that followed, David and A. Rafanelli wines were gaining recognition.

In 1986, Americo died and David and Patty took over the winery. The following year, David entered a bottle of A. Rafanelli Zinfandel in the Sonoma County Harvest Fair and won a gold medal and best red wine.

After winning in two categories of the competition, their business expanded. “We had people knocking on the doors,” David recalls. “We got a guest book and started a mailing list.” Patty maintained the list, writing the names and addresses of their patrons on recipe cards. The Rafanelli label went on to win three more competitions in 1990, 1991 and 1992, and the changes continued at the estate as David planted 15 additional acres on a steep hill, and built wine caves into the side of a hill.

As the years melted away, the Rafanelli girls grew up in the family business. “I worked in the bottling line, the tasting room. Then went away to college and returned and started at the bottom with the crew,” says Rashell, better known as Shelly to family and friends. In 1996, she graduated from California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo with a degree in agricultural business and began working full time at the winery. Four years later she was officially appointed winemaker. Her younger sister, Stacy, eventually stopped practicing law and joined the business, working as director of winery relations and sales. Their youngest sister, Victoria Americo, better known as Tori is married and lives in Southern California.

Traditional winemaking

Over the last several decades, the winery has grown and evolved, transforming itself into a full-time family operation, but it still produces wine using traditional practices, true to their Italian roots. “We have four generations of winemakers from the same family. The style is passed down to each generation,” says Shelly. “Our grapes are all hand-harvested and hand-sorted, aged in oak and we do open-top fermentation in small lots, which are manually punched down every four to six hours. It’s a natural style of winemaking,” she adds. “ We rack the wines, instead of using ‘fining’ additives or filtering them. There’s more sediment, but it doesn’t strip body or color.”

Adds David, “The consistency comes from the vineyards and the style of winemaking. This is why we’ve never redesigned the wine label.”

Why Alberto included his initial on the label and not Letizia’s, is still unclear. “It’s still one of the mysteries,” says Shelly. “Letizia was behind a lot of the hard work.”

In an era of wine club memberships and elevated tastings, the charm of A. Rafanelli Winery is that it keeps its day-to-day operations simple. David and Patty oversee the winery, which produces 11,000 cases a year. Patty personally delivers wine to select restaurants in San Francisco and the North Bay; Stacy manages sales and the mailing list. Shelly serves as winemaker, and her husband, Craig, serves as the director of all vineyard operations. It’s not always easy, of course. “Italians are passionate people,” says Shelly with a laugh. “Working in a family business, everything is centered around grapes and wine—we live and breathe grapes. Sometimes we disagree, but in the end we’re all working toward the same goal— to making high-quality wines that we enjoy sharing.”

In an era of wine club memberships and elevated tastings, the charm of A. Rafanelli Winery is that it keeps its day-to-day operations simple. David and Patty oversee the winery, which produces 11,000 cases a year. Patty personally delivers wine to select restaurants in San Francisco and the North Bay; Stacy manages sales and the mailing list. Shelly serves as winemaker, and her husband, Craig, serves as the director of all vineyard operations. It’s not always easy, of course. “Italians are passionate people,” says Shelly with a laugh. “Working in a family business, everything is centered around grapes and wine—we live and breathe grapes. Sometimes we disagree, but in the end we’re all working toward the same goal— to making high-quality wines that we enjoy sharing.”

The fourth generation

More than a century ago, Letizia was teaching Alberto how to farm and make wine, using the same practices she learned as a young girl. “She was determined to define her future by herself, and not by her family,” says Stacy. She and her sister, Shelly, are at the helm these days, much like their great grandmother, and David has stepped back his role and takes great pleasure watching the next generation lead the way. “It’s very gratifying,” he says.

This autumn, as the fruit ripens and the leaves turn brilliant shades of gold and orange, it’s harvest season again for the Rafanelli family. The day begins at 5 a.m. for Shelly and the cellar crew, who start with fermentation tank punch-downs. At daybreak, the vineyard crew begins picking. “We like to bring in the fruit as cold as possible,” says Shelly. Meanwhile, prep work begins before they start hand sorting and crushing the grapes. Stacy runs the crush equipment and helps her sister in the cellar.

David hauls grapes in one of the family’s post-war Chevy pickups that his grandfather purchased in 1945. And Patty helps weigh in the grapes and drives the forklifts, and always makes a homemade lunch for the crew. “And one of her more important jobs is getting the grandkids—Jordan and Caden—to and from school,” says Stacy with a smile.

As for the vintage of 2019, the family is optimistic. “It’s a good size crop with a healthy canopy that helps ripen the grapes,” says David.

“The weather is good and cooperating. The fruit looks good, too,” says Shelly. “But Mother Nature has the final call.”

A. Rafanelli Winery remains a well-regarded red house in the industry, known for its exquisite, award-winning wines. And if you’re from Sonoma County, you know a bottle of Rafanelli isn’t so easy to come by unless you’re fortunate enough to be on their mailing list, but David, who still has his grandmother’s pearl-handled pistol, takes it all in stride. Still a farmer at heart, chances are you’ll find him in the barrel room visiting with guests, explaining the harvest process and sharing the family history. Says David, “The story always makes the wine taste better.”

Author

-

Karen Hart is the editor of NorthBay biz magazine, keeping her finger on the pulse of the North Bay, directing content and leading day-to-day operations of the editorial team. An award-winning writer, Karen brings more than 30 years of experience to the position. She is a member of the California Writers Club, and serves on the Journalism Advisory Council at Santa Rosa Junior College. She moved to Sonoma County in 2000, and she’s here to stay.

View all posts