On a bend in the Russian River with the Alexander Valley, Dry Creek Valley and Chalk Hill American Viticulture Areas on its periphery, Healdsburg has much to offer. It’s a magnet for those seeking a Wine Country experience, but at the same time, residents treasure its small-town charm and quality of life. Those interests produce competing visions of what the town should be, and residents are often concerned that abundant visitors will impact the small-town ambiance. Yet tourism isn’t new to Healdsburg. It’s been a favorite vacation spot for more than 100 years. “Tourism has always been very much part of Healdsburg,” says Holly Hoods, executive director and curator of Healdsburg Museum and Historical Society.

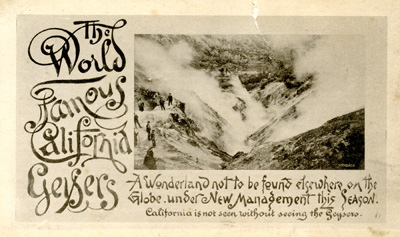

The earliest destination for tourists was The Geysers, northeast in the Mayacamas Mountains. Healdsburg was the staging area, and horse-drawn vehicles took visitors to view emissions of hot steam and bathe in pools of mineral water. In 1871, the railroad arrived, and while it opened the market for agricultural products, it also offered passenger service. Healdsburg was suddenly an easy getaway for those who lived in San Francisco, and the town encouraged travelers with round-trip-ticket promotions. “There was a big effort to bring people in summer—people built summer cabins,” says Hoods. Fitch Mountain, in particular, became a destination, and people spent evenings at dance halls with big bands. In 1910, Villa Chanticler (later changed to Chanticleer) opened on the mountainside, drawing French-speaking San Francisco residents to Healdsburg with French food, fine wine and a Bastille Day celebration in July.

Grapes, prunes and a galvanizing idea

Healdsburg always was an agricultural community. In the early years, the hills and valleys were planted with grapes, hops and prunes. Change came in 1919 with the passage of the Volstead Act, which the federal government enacted to enforce Prohibition. “The wine industry that we know today had its roots much, much earlier, in the 1860s, but Prohibition cut it off at the knees,” says Hoods. With most wineries and brewers forced out of business, the market for winegrapes and hops vanished, and growers replaced their crops with fruit trees, principally prunes, which became a vital component for a changing local economy.

Healdsburg positioned canning and packing plants next to railroad spurs so prunes could easily be dried and shipped to market, leading to widespread sales and distribution. Prunes were so prominent that the local baseball team took the name Prune Packers, and in 1929, the city adopted the slogan “Healdsburg: The Buckle of the Prune Belt.” It was an apt description, and the city took advantage of it to attract tourists by offering blossom tours in the spring. “People would come for the beautiful prune trees,” says Hoods.

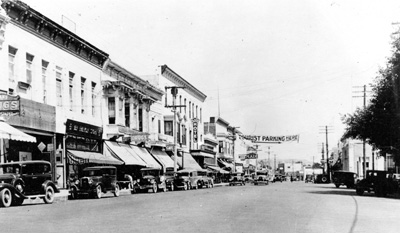

By the 1950s, prunes weren’t increasing in value, so growers began replacing prune trees with grape vines. By the 1980s, all the orchards were gone and a new wine industry was on the rise, but downtown Healdsburg wasn’t faring as well. “It was looking kind of shabby. It was not a welcoming downtown,” says Hoods. At one time, Healdsburg had a lot of bars. “The bars were part of the business community, like tasting rooms are now,” she says. Over time, however, the area around the plaza became run down with empty and boarded-up buildings, with nothing to offer visitors, or anyone for that matter.

Then, in the 1970s, Larry Wilson, an out-of-town developer, bought vacant downtown properties and promoted a zany idea—The Kingdom of Healdsburg. His concept was to develop Healdsburg into a themed city with flags from different nations on display in the plaza. The police would wear lederhosen, and it would be similar to Disneyland. Residents were outraged, and the planning commission eventually opposed the idea. “There was this great upheaval in Healdsburg over what was going to happen downtown. It was a year and a half of this close call,” says Hoods. Angry that he couldn’t do what he wanted, Wilson sold his property and appeared on the cover of New West magazine flipping off the city.

Vision

The Kingdom of Healdsburg fiasco was frightening for residents, but it forced them to consider how the city should grow. In 1982, the town commissioned the Regional Urban Design Architectural Team, a group of outside consultants, to assess Healdsburg, look at its past and plan its growth.

Members of the community participated in focus groups and shared how they wanted to use the plaza. Among the challenges, they had to find ways to draw revenue to the city, and they decided they didn’t want to attract big-box retail stores but would encourage boutiques instead. “It’s a benchmark in the history of planning,” says Hoods, and the results are evident. “One thing I like about the downtown is that people value it so much. There’s a real effort to keep the development at a scale people are comfortable with,” she says, adding that historical and contemporary architecture blend well. “The plaza still functions like the town’s living room.”

In the 1970s, several downtown buildings were condemned and torn down, with the city wanting a hotel in their place. It took longer than anticipated to find a good fit for the community, but the city ultimately approved plans for Hotel Healdsburg, which opened in 2001. It had a substantial impact in revitalizing the downtown and attracting more businesses. Circe Sher, president of Piazza Hospitality, which developed the 55-room hotel, explains that her father, the late Merritt Sher, and Paolo Petrone were both from Marin County. Paolo developed several small hotels already and they both enjoyed the short trip north to visit Healdsburg. “My father loved the scale of the plaza and the walkability,” she says. The two men appreciated Healdsburg’s heritage, as well as the character of farm and wine country, which they found rustic and interesting. The Shers and Petrone established Piazza Hospitality and set out to design a full-service hotel in Healdsburg with a modern design that incorporated features of the plaza and included retail and a restaurant for fine dining.

“We created a concept that didn’t already exist,” says Sher. One of the goals was to create a hotel that would be compatible with the plaza, she adds, and the key was making it two buildings connected by a grass walkway with ground-floor retail to maintain the walkability of the plaza.

Once open, the hotel attracted visitors who were eager to explore the area. The influx of tourists resulted in a new wave of businesses, including more hotels. Piazza Hospitality went on to develop h2hotel and Harmon Guest House, which is named for Healdsburg’s founder, and the new hotels were appropriate for the area and generally well received. Piazza Hospitality solicited feedback from residents, understood the community’s goals and worked within zoning guidelines, which helped solidify support.

“People understood the kind of projects we did and knew us personally,” says Sher, who is a Healdsburg resident. They encountered some opposition on the room count for Harmon Guest House, which made sustainability as a priority, so they reduced the number to 39, resulting in a more popular project.

Hotel Healdsburg was a turning point for the city’s image. In the 1980s and ‘90s, the tourism industry was lagging and downtown businesses were facing challenges. “It [the hotel] brought a hotel and restaurant that created a different vibe in the downtown area,” says City Manager David Mickaelian.

It was a catalyst for further development, sparking economic vitality and adding diversity. “We want to do what we can to make sure it’s a vibrant area,” he says. As a result, locally owned businesses that serve residents, such as a barbershop, an insurance office and a pet store are also close to the plaza. “It keeps the community real, having that kind of eclectic approach.”

Maintaining balance

Hotel development has pros and cons. Mickaelian describes tourism as an important cog in the economic wheel and explains that typically, visitors stay for a few days and spend money eating in restaurants and shopping, which contributes to the local economy. They also pay Transient Occupancy Tax (TOT), which is a room tax of 16 percent that all visitors pay when they stay in a hotel, motel, resort, inn, suite or B&B within Healdsburg’s city limits. Most of TOT—80 percent—goes to community services, such as recreation programs, the senior center and open space, while 2 percent goes to affordable housing and homeless programs. “The lion’s share supports what the community believes is important. It’s a critical piece for us,” says Mickaelian, who adds that the city is always trying to find a balance between tourists and local residents.

Sher believes that hotels enri ch the lives of people who live in Healdsburg. “Without the visitors, we wouldn’t have all the great restaurants,” she says. Additionally, tourists help sustain the unique businesses around the plaza and the local wine industry, which in turn support the residents of Healdsburg. “We are stewards of the community,” she says, adding that Piazza Hospitality has contributed to the restoration of Foss Creek and hires local young people when possible.

ch the lives of people who live in Healdsburg. “Without the visitors, we wouldn’t have all the great restaurants,” she says. Additionally, tourists help sustain the unique businesses around the plaza and the local wine industry, which in turn support the residents of Healdsburg. “We are stewards of the community,” she says, adding that Piazza Hospitality has contributed to the restoration of Foss Creek and hires local young people when possible.

Not everyone is pleased with the pace of hotel development, however. In December 2018, responding to fears that excess tourism would spoil the plaza area’s character, the Healdsburg City Council approved an ordinance that limits the number of hotels in a four-block radius of the plaza and restricts new hotels in the downtown zone to five rooms. Mickaelian explains that council members were trying to find a balance between current hotels and future developments. “I think they took a measured approach,” he says.

He reports that people in Healdsburg want more housing, and hotels outside the downtown zone provide opportunities for that demand. Comstock Homes, a Southern California developer, submitted plans to the city for a multi-use project on 32 acres in north Healdsburg, well away from the plaza, called North Village. It entered the review process in August. If approved, it will include commercial space and 352 units of senior and affordable housing as well as a 12-room hotel “We’re able to negotiate with hotels to provide affordable housing,” says Mickaelian. “The days of a hotel simply coming to town without providing housing are probably over.”

Holistic approach

Increased housing would clearly be an asset, allowing more people who work in Healdsburg to live in town, but tourists are still going to visit. The Healdsburg Chamber of Commerce & Visitors Bureau is charged with marketing the city, but its overall goals are twofold: to attract visitors and to develop a diverse, robust business environment that engages local residents as well as tourists. It’s a broader role than the chamber played in the past, but as a dual agency, its tasks are complementary and centered on the community. “One thing the chamber has focused on in the last year or two is how we communicate with the local community,” says Alan Baker, board chair. “If citizens don’t shop in our stores, we’re not going to make it. You can’t survive on tourism alone.”

The chamber also has a contract with Healdsburg to promote economic development for the city. It provides services for members who pay dues and it’s leveraging those relationships to create economic diversity. The Healdsburg Tourist Improvement District (HDIT), a committee of the chamber, is also assessing hotels that have a self-assessed HTID tax, and it’s marketing to visitors, who include PG&E line workers and friends of locals. “Hotels aren’t just serving people who are visiting as tourists,” Baker points out. Previously, a lack of funds limited marketing, but now, that’s changing.

“We’re the backstop to support the businesses,” he says, adding that the chamber keeps the visitors center open to inform people about where they can go to make the most of a stay. “It all serves the greater goal of making Healdsburg attractive.” The end result is a thriving food and lodging industry with local benefits.

TOT also keeps the town thriving. “We’ve done a pretty good job of leveraging the money that comes from TOT and putting it back into community services.” Baker also observes that hotels and restaurants create jobs, and their guests support other businesses for miles around when they explore the area and spend money. In addition, people who visit Healdsburg sometimes relocate there, often bringing their businesses with them. He considers that a big deal, as new residents bring fresh energy and ideas. “Having such an attractive place to live draws talent,” he says.

Baker realizes, though, that Healdsburg is currently experiencing a strong anti-hotel and tourist sentiment. “I understand,” he says. Still, he cautions against reacting too quickly. “We need to do more research before we limit growth.” He believes the ordinance imposing limits downtown was written hastily and in a way that will force any new lodgings to be luxury hotels. “We should build a more robust future rather than restrict ourselves to the ways of the past.” That includes recognizing the role tourism plays.

Meanwhile, Healdsburg continues to welcome visitors. It has a reputation as a Wine Country destination, and outdoor activities are an attraction as well. “We have a lot of cool activities in this area,” says Mickaelian. Popular pastimes include hiking in the city’s 300 acres of open space, races such as the Healdsburg Wine Country Half Marathon and water sports on the Russian River. “Biking is incredibly popular in Healdsburg,” he adds. A bike-share phone application helps fuel that trend, reducing the amount of cars on city streets. Additionally, a pathway through town makes walking easy, further easing traffic for residents and tourists.

In the past, most visitors were from the Bay Area, and that still holds true. Sher estimates that 65 percent of Hotel Healdsburg’s guests are from San Francisco and its surrounding area, though a substantial number are from southern California and nearby states. In addition, Texans like to visit Healdsburg when their state’s weather is too hot or cold. She believes that people come for the great food and wine, but the environment and small-town feeling are draws too. “We act as a second bedroom for families in Healdsburg who have friends and family visiting, and it gets busy around Thanksgiving and the holidays,” she says. “That’s really nice to see.”

Healdsburg has evolved over the years, but its character remains much the same. People have always come for wine, recreation and family time in a special environment and will continue to do so because the appeal is enduring. Tourism is firmly established and here to stay.