Goat milk is the most widely consumed milk in the world. Interest in the U.S. is relatively new, yet the trend seems to be catching on. Dairy goats showed the largest increase in livestock numbers, growing 61% from 2007 to 2017, according to the latest data available from the U.S. Dairy Association. So what’s driving the surge? In the 1980s goat cheese became popular with celebrity chefs and the farm-to-table movement. Travelers to Europe discovered goat’s milk cheese consumed there for centuries. And then there’s the focus on health. Goat dairy, with smaller fat globules, is easier to digest than cow milk. And it’s a nutritional powerhouse, with more calcium, more potassium, more magnesium and more vitamin A than milk from cows. Goats, needing less water and producing less methane, could be part of the climate change solution. There are also a variety of goat milk skin-care products. And new on the shelves are goat milk products for pets. And let’s not forget goat yoga! (No kidding—it’s a hot fitness trend.) The untapped U.S. market offers much potential for goat milk products. Perhaps that’s why European dairy companies, with expertise and financial resources, are acquiring California’s goat milk pioneers. Here are some of their stories.

Laura Chenel

In the 1970s, Laura Chenel, a young woman with a passion for good food and goats started raising dairy goats. Her name would become synonymous with artisan goat cheese, yet her initial attempts at cheesemaking didn’t pan out. She traveled to France where cheese has been made since the eighth century, and 99% of households eat cheese at least once a year. There she apprenticed with four farmstead cheesemakers to learn French-cheese making. On returning to the U.S., she combined French techniques with her own creativity and began selling goat milk cheese in 1979. She got a big break early on. Alice Waters, of the famed Chez Panisse restaurant, loved her cheese and placed a standing order for 50 pounds a week. Using Chenel’s fresh cheese, she created the iconic California goat cheese salad—baked, sliced goat cheese in a bed of mesclun greens.

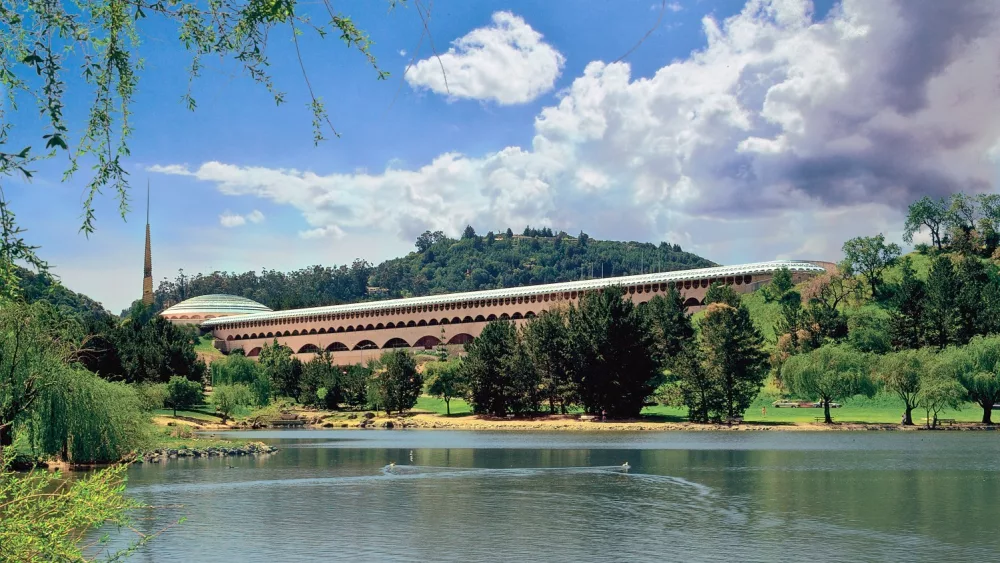

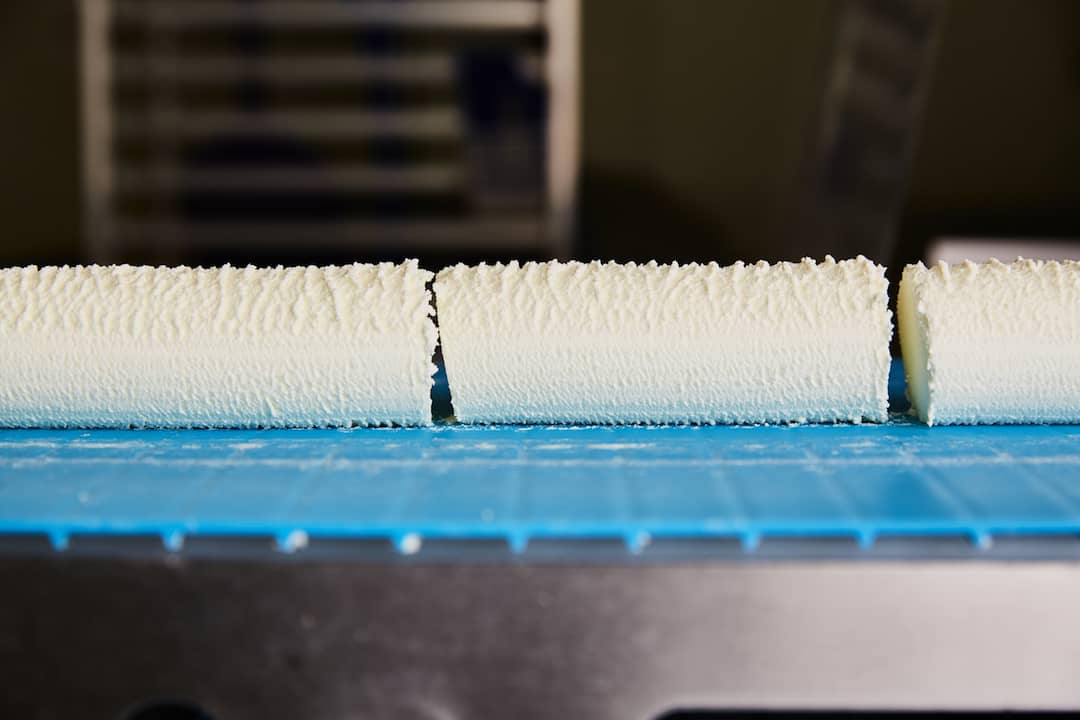

In 2011, the company built a 40,000-square-foot state-of-the-art production facility on the outskirts of Sonoma. It was the first creamery in the U.S. to receive LEED Gold certification. Milk is provided by family-owned goat dairies in California, Nevada, Oregon and Idaho. Every morning a refrigerated truck with goat milk arrives at the Sonoma creamery. Farmers are paid based on volume, with an additional payment tied to nutritional composition.

Today, 86% of the Laura Chenel cheese sales come from west of the Rockies. Products can be found at most grocery stores, or purchased online.

Redwood Hill Farm & Creamery

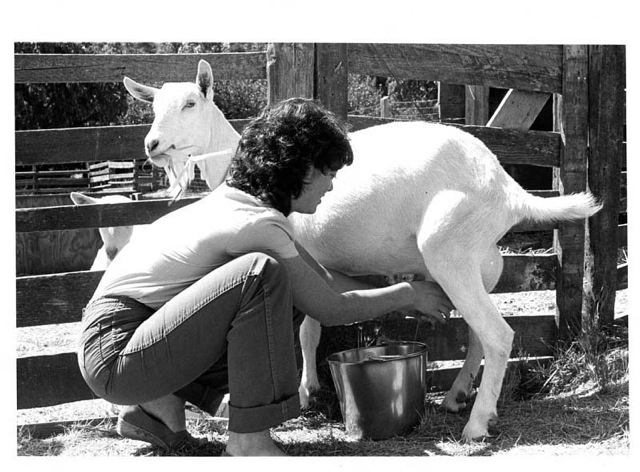

In 1968, the Bice family moved from Los Angeles to a farm in Sebastopol. Jennifer, the oldest of 10 children, joined 4-H, an agricultural youth group, and fell in love with goats. Her passion evolved into Redwood Hill Farm & Creamery, a national brand known for its flavorful goat milk yogurt and kefir products. She likes to say it was a “4-H project that got out of control.”

Redwood Hill Farm was the first goat dairy farm in the U.S. to receive the Certified Humane® designation from Humane Farm Animal Care. All goats in the herd are registered with the American Dairy Goat Association (AGDA). Goats are raised for show to provide dairy goat genetics to other farmers, and for the high quality of their milk.

In 2015, Jennifer sold the creamery to Swiss-based Emmi, a global, publicly traded company, which is to this day majority owned by a cooperative of Swiss dairy farmers. Emmi’s annual revenue for 2021 was approximately $4 billion. “I wanted to ensure that after I retired, Redwood Hill would continue to thrive as a Sonoma County business, a community resource, and continue making wholesome, organic food accessible and affordable for everyone,” Jennifer says. “Emmi has more than 100 years of dairy experience. We can learn from that. And my wonderful employees get to stay on, as well as the management team that helped me grow the business.”

Redwood Hill Farm is one of seven goat milk suppliers for the creamery that has 100 employees. Those seven farms tend to an estimated 6,500 goats, that give the milk that is processed at the creamery an estimated 10 million pounds of milk annually.

Products include yogurt, which comes in plain as well as vanilla, blueberry and strawberry. There’s a plain kefir, and a blueberry pomegranate acai for berry lovers. “Our yogurt and kefir is velvety, slightly tart and dense with nutrients, probiotics and protein,” says Helen Lentze, senior director of marketing, Redwood Hill Farm & Creamery. “Being lower in lactose and with smaller fat particles, goat milk is easier to digest than cows milk.”

Dairy goat breeds include Alpine, La Mancha, Nubian and Saanen. As a breeder, they sell kids to other area farmers. To supplement the goats’ diet, the farm grows tagasaste, a high-protein, fast-growing shrub. “The goats love it,” Scott says. “Tagasaste requires little water, is a perennial and sequesters carbon.”

Several years ago, local craft brewers approached Redwood Hill about growing hops. “You grow it, we’ll buy it,” they said. And grow it Scott did, initially planting a quarter-acre hop yard, with three varieties—Columbus, Cascade, Chinook and has now added the Bitter Gold variety. “The hop plant is a vigorous climber,” he says. “During the four-month growing season, the hops travel up coconut fiber strands to heights of 20 feet. We spread composted manure from our goat barns in the hop yard. The mulch retains moisture and allows the plants to thrive.” Fittingly, one of the hops customers is the Crooked Goat Brewing. Another customer, Fogbelt Brewing Co., named one of its beers “Redwood Hill.”

Meyenberg

Meyenberg is also an Emmi-owned California company. In 1934, Harold Jackson set out to find a nutritious, tolerable food for his young son, Robert, who suffered from food allergies and asthma. He discovered evaporated goat milk, a product being produced in California by Swiss immigrant John Meyenberg. Seeing how the milk helped his son, Jackson formed a company and began marketing the product. In 1944, Harold died unexpectedly and Robert, at age 25, took over as president and CEO. With wife Carol as vice president and chief marketing officer, the couple grew the business into the country’s largest producer of whole goat milk, powered goat milk, goat milk butter, and evaporated goat milk. In 2017, the Jacksons sold the company to Emmi.

Meyenberg works with 25 dairy suppliers tending an estimated 13,000 milking goats. From their production facility in Turlock, Calif., the company produces more than 30 million pounds of goat milk annually.

When shelf stable cow milk wasn’t available during the pandemic, many consumers switched to Meyenberg’s powdered or evaporated milk products. “As the pandemic abated, we expected them to go back to drinking cow milk,” says Helen Lentze, senior director marketing. “To our delight, that hasn’t happened. Seems they like the taste.”

Meyenberg is all about innovation. Based on its experience providing goat milk to zoos and animal welfare organizations, the company launched a new brand, Tailspring, a milk replacer for puppies and kittens whose mothers are not able to provide for them. “The product is fortified with essential amino acids, fats, carbohydrates and vitamins to promote good health in growing pets,” says Lentze. Based on milk replacer’s success, Tailspring recently introduced food toppers for dogs and cats, and dog goat milk chews for calmness, joints and skin.

Always keen to support new markets, Meyenberg supplies goat milk powder to Beekman 1802, the world’s largest goat milk skin-care company.

Toluma Farms & Tomales Farmstead Creamery

Tamara Hicks and David Jablons, with backgrounds in health care, recognized the positive impact nature, a healthy ecosystem and fresh, nutritional food can have on one’s mental and physical health. With that in mind, the couple purchased a defunct 160-acre dairy in West Marin. “The land was in bad shape,” Hicks says. “It had become a dumping ground for old tires and waste.” Working alongside daughters, Josy and Emmy, and with the support of several conservation organizations, they set about restoring the property. “That turned out to be a multi-year effort,” she says.

Toluma Farms is not just about preserving its dairy heritage. It’s also about preserving the traditions of the Coastal Miwok. Several of the creamery’s cheeses have Miwok names. And the farm is embarked on a willow-planting project together with the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria (FIGR), Marin Resource Conservation District (MRCD), Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS) and Point Blue Conservation Science. The willows will be used for the Miwok’s traditional basket making.

“Redwood Hill Farms helped us get started,” Hicks says. “We bought our goats from them. And they advised us in setting up the milking parlor, on animal husbandry issues and milking protocol.” 150 acres of Toluma Farms land is organic and serves as pasture for the farm’s Animal Welfare Approved 200 goats and 80 East Friesian sheep.

The kidding season from mid-February to mid-May was a busy time. “190 baby goats were born,” Treviño says. “Fifteen became part of the herd. The remainder found a home with a farmer who rents out his herds to clear dry brush and help prevent wildfires.” Drought is an ongoing issue. “Last year was the first time we had to truck in water,” Treviño says.

The farmstead cheese products can be found at local stores and restaurants. And when Dr. David Jablons isn’t at UCSF performing thoracic surgeries or doing cancer research, he can be found slinging cheese at farmers markets.

Toluma Farms, focused on land stewardship, sustainability and addressing climate change, collaborated with Marin Carbon Project on the design of a plan to help sequester carbon. “We took on the projects of highest impact first,” Hicks says. “Last year, we spread compost on the upland pasture to stimulate forage growth and increase carbon sequestration.” In February, an enthusiastic team from MALT, Marin Resource Conservation District, Students and Teachers Restoring A Watershed (STRAW), Point Blue Conservation Science and the Carbon Cycle Institute, planted 500 trees, shrubs and grasses along the ridgeline. “The native Monterey cypress, California coffee berry, coast silk tassel and other species will grow to different heights forming a quarter-mile-long windbreak. This will lock up carbon and protect the pastures from drying out. Forage will be able to grow later into the summer, increasing the farm’s productivity,” says Hicks.

In a world increasingly dominated by climate change, goat dairy is destined to play an important role. Goats can survive in hostile environments, consume less water and emit less methane than other livestock. And what’s not to like about a goat? They have great faces. They’re sociable. They produce milk that can be turned into tasty, nutritional cheese, yogurt or kefir. They’re good for the gut. And good for the planet!

[Lead photo courtesy of Redwood Hill Farm & Creamery]