Reading can be a source of joy for young learners who decipher words easily, but when children struggle to make sense of the words in front of them, it becomes an exercise in frustration that can have a lasting impact. Literacy is one of the keys to success in life, and the odds are against those without it. If children aren’t fluent readers by the end of third grade, they’re less likely to graduate from high school, and their risk of getting on the wrong side of the law and ending up in prison increases. In September 2021, The California Reading Coalition released its first California Reading Report Card, which showed that only half of the students surveyed could read at grade level, putting their chances for future success in doubt. The report focused on 287 school districts that serve 100 or more low-income Latino third graders, and San Rafael City Schools and Sonoma Valley Unified School District were among those with low rankings, having only 21% and 19% of students, respectively, meeting or exceeding grade-level standards. Later that month, Tony Thurmond, state superintendent of public instruction, announced the formation of a statewide literacy task force to explore ways to help all children in kindergarten through third grade meet grade-level standards by 2026 to reverse the current trend.

Children have difficulty mastering reading for a variety of reasons. They might be dyslexic, as are Gov. Gavin Newsom, and actress Keira Knightley, or they might have undiagnosed hearing or vision problems. Children from families with a history of difficulty reading sometimes face challenges as well. And although educators try to avoid stereotyping, they observe that children from lower socioeconomic areas tend to struggle more, and many are English language learners with parents whose literacy level is low. Reading and books aren’t among early experiences for many of those children, and so they’re often already behind when they start kindergarten. “We know that there are a lot of children who come to school without preparation,” says Barbara Nemko, Ph.D., superintendent of the Napa County Office of Education and a co-chair on the Statewide Literacy Task Force. “They don’t know the alphabet, don’t have books and are not being read to. If they aren’t from English-speaking families, it can be more difficult.”

Early learning

When parents read to their young children, it makes a difference. “You have to take advantage of those early years,” says Amie Carter, assistant superintendent of education services, Marin County Office of Education. She explains that if preschoolers don’t have someone read to them, they arrive in kindergarten with a limited vocabulary, and if they’re from households that aren’t rich in literacy and books, they’re at a disadvantage.

Some children learn to read naturally, but most don’t. “The brain is wired to speak. It is not wired to read,” says Lauren Ridgway, English Language Arts/English Language development coordinator, Sonoma County Office of Education. She explains that reading usually requires direct instruction, and while some kids will learn no matter what, others need lessons in phonics to become solid, proficient readers.

Phonics-based instruction is a structured approach that teaches children to break down words into small components and learn how to read, spell and pronounce them. Whole Language, which was the predominant method of teaching reading in California during the 1980s and 1990s, treats words as part of a system in which whole words function in relation to each other in context. Each method has its advantages, and the discussion over which is better has gone on for decades. Nemko evaluated phonics and Whole Language to find out which is better for her doctoral dissertation at the Graduate School of Education at the University of California, Berkeley. She had learned to read intuitively, as children of well-educated parents often do, and so she began with a bias for Whole Language. She was surprised, however, to discover that for many children, phonics is better. “My intuition was wrong,” she says. As words get larger and larger, she explains, people have difficulty pronouncing them if they haven’t learned to read using phonics. She believes that instead of getting into the culture war of which method is more effective, it would be better to consider the sequence of reading and identify students who need more instruction and those who need less and provide them with a good foundation.

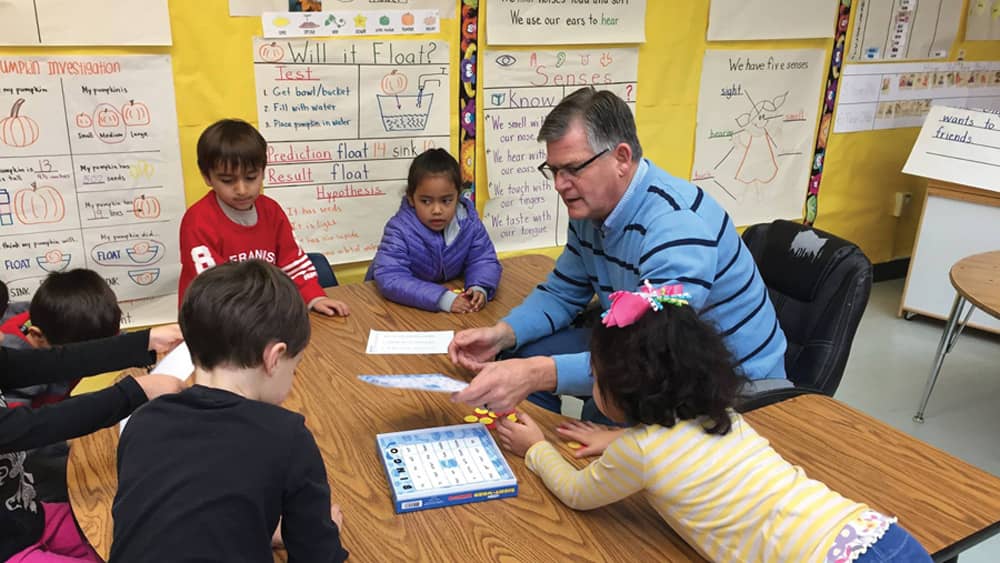

Carter points out that teachers can’t be at either extreme. “For a lot of kids, the phonics approach has to be the right one,” she says, but educators must discriminate between the two methods and determine what works best for their students. Reading is complex, she adds, and students need time, feedback and support, and correcting errors in real time is important. “A lot of people don’t understand how complex and multifaceted reading and literacy is,” she says. Ideally, an educator will sit with students one on one and work with them on anything from sight words to blended vowels, depending on an individual child’s needs. She observes that a lot of micro skills go into literacy, and it takes a skilled educator to help children become proficient readers.

Turning point

Achieving proficiency by third grade is critical if children are to be successful in higher grades. Ridgway explains that in kindergarten through third grade, children are learning to read, but once they reach fourth grade, they’re reading to learn. “There’s that really big shift that happens in fourth grade. It’s important to catch kids and give them support before they reach that point, or they’ll fall behind in other areas,” she says. Social issues also come into play because what happens in the classroom often affects social status. “We sometimes start to see kids acting out,” she says, explaining that they think it’s better to misbehave than to be perceived as someone who can’t read.

Carter points out that students read a lot of nonfiction and academic content beginning in fourth grade, and if they can’t read fluently, it’s going to be incrementally challenging for them. “They’re just going to feel frustrated,” she says, because they won’t be able to handle the curriculum.

Identifying children who are facing challenges early is important. “If you don’t intervene early enough, a child can end up hating school and especially hating anything involved with reading,” says Nemko.

North Bay schools have adopted a variety of methods for helping students to succeed. In Sonoma County, most schools use a two-tier approach and offer phonics and reading instruction in the classroom and additional small group instruction to students who are falling behind. Ridgway reports that each school district has its own plan for students who need more help, including consideration for frequency and duration of instruction. A teacher or paraprofessional will work with the students, focus on different things depending on the situation and look at the science of reading and the best practices for teaching kids to read. The idea is a universal design for learning—which considers different methods of teaching and learning and gives all students an equal opportunity to succeed—that reaches all levels. “That really targets the classroom and makes sure that all kids can access the content,” she says.

County offices of education are agencies that offer services to the schools and districts in their counties. Marin County takes a variety of approaches. “We support a lot of professional development,” says Carter. Last year, MCOE focused on intervention, particularly for English learners, and looked at research and evidence-based practices to help teachers find solutions. “There’s a whole arsenal of strategies that our schools use,” she explains, and they include leveled readers and small group instruction. In addition, interactive digital learning games can help with blended sounds and consonants. “What’s most important is that we have a system for monitoring,” she says.

“The Napa County Office of Education is fortunate to have been awarded one of the state literacy grants,” says Nemko, and NCOE’s role is to do teacher training. “We have our own staff trained,” she says, and they will train teachers when districts and schools make a request. “We recently completed one week of staff development for our partners in this grant, which include Riverside County, Siskiyiou County, Calistoga JUSD, and Napa Valley USD.”

Innovation

Students in two schools in Sonoma Valley Unified School District have shown a significant improvement in both their reading and math skills thanks to the Grade Level Proficiency Project, which grants from the family of Gary Nelson, chairman of emeritus, made possible. Laura Reed, former executive director of K3 innovation, a new nonprofit that will offer the program to kindergarten through third grade in additional schools, explains that Sonoma Charter School has completed a three-year pilot project, while Sassarini Elementary School in Sonoma is entering its third year. “We commit ourselves to a school for three years,” she says. The program includes coaching for teachers and the use of adaptive technology in the classroom. It uses Lexia Core5 Reading for students, and Lexia Learning offers coaching to teachers, with a trainer showing them how to use the program with a class. The teacher then uses easily accessible resources to offer individualized support to students. “We partner with a school and support every single classroom,” she says. Coaches also work with the teachers to see how much intervention a child requires. “We make sure there’s an instructional aide in every single classroom,” she adds, explaining that the aide assists the teacher and leads independent or small-group instruction as well.

Elementary schools in SVUSD uses Wonders, a language arts program from McGraw Hill that includes print and digital resources that provide a strong foundation for building literacy skills. In the Grade Level Proficiency Project, teachers use Wonders as well as Lexia, which offers a personalized reading program to determine how much help a student needs. Coaches help teachers make the links between adaptive technology tools and the materials the school district adopts, and the result is high-level teachers who have support and are equipped to use Lexia’s tools for differentiated instruction in their classrooms. Thus, a teacher’s practice improves, and students get individualized support. Reed reports that students at Sonoma Charter School went from 30% to 90% proficiency in reading, and performance remained consistently high during the pandemic, when students were attending classes remotely. Surveys and interviews with teachers were positive as well. “They’re so grateful,” she says. “Their skills and practices are changing in a good way.”

In Napa County, Nemko was instrumental in implementing Footsteps2Brilliance, a program that starts even earlier, when kids are preschoolers. She explains that children get libraries of books in English and Spanish on iPads, and accompanying exercises help with visual-sound correspondence and fluency. They can switch from one language to another or get the meaning of a word with a tap on a screen, and parents can listen in Spanish and then have the child listen to the story in English.

“iPads are so incredibly engaging,” she says. If a child taps on a clock in the story, you will hear the clock tick. Or, touch the picture of a cow and it might stamp its feet and say, “Moo.” In addition to sound effects there is often music, so the child has an interactive experience with the iPad that she or he can initiate, as often as desired, making iPads an effective way for children to become familiar with and learn to love books. Games and enrichment activities go along with stories, and a child either gets praise for getting answers right or hears a friendly voice say, “Oops, try again,” if they make a mistake. “All of that helps them prepare for formal learning to read in school,” she says. A component for parents lets them do activities with their kids, and, in an added benefit, if parents have low literacy in English, and their literacy is low, they can sit with their children and learn English, too.

Nemko started her teaching career in elementary school and is a proponent of using technology in the classroom. She explains that it’s tricky to teach to different levels of readers when using textbooks, but with iPads, each child can get a lesson on his or her device at the appropriate reading level. If the lesson is on earthquakes, for instance, the teacher starts with a classroom discussion about what the students already know and then moves on to what they want to learn. “Then when the lesson moves beyond the discussion to actually reading, each child can read the same story on his or her own reading level on the iPad,” she says. As a result, kids who read well aren’t bored, and those reading at a lower level aren’t overwhelmed.

New approaches

NCOE is working with the UCSF Dyslexia Center, which has developed an early screening device to identify problems before they start. It can tell if a child is potentially at-risk of having difficulty learning to read. “You can find out pretty quickly using a screener if a child is accustomed to reading books and whether they’re being read to, seeing people and visiting the library,” says Nemko. In addition, NCOE is working with Breaking Barriers, a statewide initiative that looks at students who are having difficulty in high school, particularly continuation high schools, and finds out which elementary schools they attended and whether they showed early signs that could have predicted later problems. The goal of Elizabeth Estes, the founder of Breaking Barriers, is to develop a screening program for older students, and Napa is working with her on a pilot project. It’s an approach that hasn’t been tried before, and Nemko sees promise in looking back at elementary school records because recognizing the signs early would make intervention possible sooner. She recently met a woman who is doing similar work in backward mapping with inmates in prisons to find out if identifying signs early could have prevented problems later in life. “The idea is catching on,” she says. “We could make a tremendous difference, but we all have to work together. Let’s work with kids before they fail, so they won’t fail.”

Nemko believes that instructing teachers in effective practices can help children in the lower grades overcome their obstacles to reading. “If we follow some of the sequence of how we teach reading, we might get better results,” she says, explaining that it’s important to give teachers the tools, starting with educational training institutions. “We have to train people who teach at the universities in the work that we’re doing so that we’re all on the same page,” she says. She explains that a common understanding of the best ways to teach reading is important so that the system teachers use will be consistent. She observes that a child who moves from one school to another shouldn’t have to change to a different system for learning to read.

Nemko was one of the co-chairs of the early learning group on the SPI’s Reading Task Force, and it addressed reading for preschoolers to third graders. The group met once a month to share ideas, and members looked at different programs and put them into a document that became part of the State Literacy Plan. Among their recommendations were screening and intervention and real books that children can hold in their hands, not just books on iPads. In addition, having access to books is another important aspect of the effort. “Every child should be given a library card from the time they start preschool. We want them to have this love of reading,” she says.

“It’s very exciting that Tony [Thurmond] has really shone a light on the importance of kids being proficient in reading by third grade,” she says. People have talked about the idea for years, she adds, but haven’t been successful in making it happen. She’s very pleased to see some new energy and positive action. And doing it at the state level means that all of California’s children will benefit, creating greater equity and a brighter future.

Sutter Reading Program: Reach Out and Read

Exposing children to books in their first five years is a proven strategy for putting them on the path to becoming proficient readers. The American Academy of Pediatrics considers reading to be a component of pediatric care. A child’s future is most influenced during the first five years of life—a time during which the brain is most rapidly developing. Research shows that reading to children during this period helps to strengthen bonding between parent and child, decrease screen time, and increase vocabulary development and literacy. Research also shows that children who enter school properly prepared are 10 times more likely to meet third grade state standards and are less likely to drop out of high school.

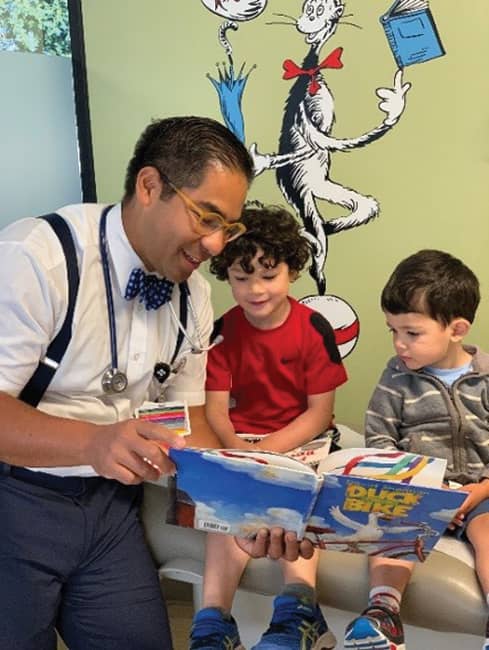

Literacy provides the foundation for doing well at school, socializing with others, developing independence, and succeeding later in life. Still, a third of young children in the U.S. arrive at kindergarten without the skills they need to succeed in school. Surveys show that only a half of parents read to their young children daily and less than 10 percent read to their children from infancy. Families living in poverty are significantly less likely to read aloud to their infants and toddlers. In addition, families with and without means are finding it difficult to access age-appropriate books to read aloud to their children. Through Sutter Pacific Medical Foundation’s Reach Out and Read Program, pediatricians and nurses give free books to patients ages six months to five years at their wellness visits and encourage their parents to read to them.

Marjorie Bohn, D.O., a pediatrician with an office at Sutter’s Stony Circle Care Center in Santa Rosa, participated in Reach Out and Read at a community clinic in San Diego, where she previously practiced. She wanted to offer the program to her patients in Santa Rosa, so in 2019, she and Emily Conner, care-center manager, created a proposal with assistance from Lisa Amador, Sutter’s director of philanthropy in the North Bay. She applied on behalf of her office to the National Reach Out and Read program, and her proposal was accepted in 2020. She then worked with Amador on a fundraising plan, and generous donors, including Lawrence and Susan Amaturo, have allowed the program to continue beyond the first year.

Bohn explains that pediatricians have a unique opportunity to engage families and promote healthy practices from the beginning of a child’s life. “We talk about why it is important to read aloud regularly, using a developmentally-appropriate colorful picture or word book. The benefits include strengthening parent-child bonding, growing a child’s imagination, helping a child attain receptive and expressive language milestones and promoting a love for reading and learning in the long term,” she says. Parents look forward to receiving a new book at each visit, and the gift motivates them to make sure their children get regular exams. Kids are also excited about getting new books, which can be an effective way to calm children who are nervous about visiting the doctor’s office. Bohn reports that parents say their children love reading time, which helps them reach their language milestones and learn more words than expected for their age.

Assembly Bills

Assemblymember Mia Bonta, who represents the 18th Assembly District in the East Bay and is founder of Lit Lab, introduced two bills related to literacy and reading early this year.

AB 2465, which she introduced in partnership with State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond, would create grant programs to provide library cards for every public-school student and allow home visits so teachers could engage parents in their children’s literary education. Barbara Nemko, Ph.D., superintendent of the Napa County Office of Education, explains that parent-teacher conferences don’t work for everyone, and home visits, which some teachers now do on their own time, are an opportunity to talk to them about what is happening at their children’s schools. The bill would also pay for the development and credentialing of 500 bilingual educators. “We have kids who speak many, many languages. What could be better than being multilingual? asks Nemko.

AB 2498 would establish a three-year pilot summer literacy and learning-loss mitigation program. Oregon-based NWEA (formerly Northwest Evaluation Association), a nonprofit that conducts assessments and supports students and educators worldwide, reports that students lose 17% to 34% of the prior year’s learning during summer break. The bill addresses that loss.

Global Book Exchange

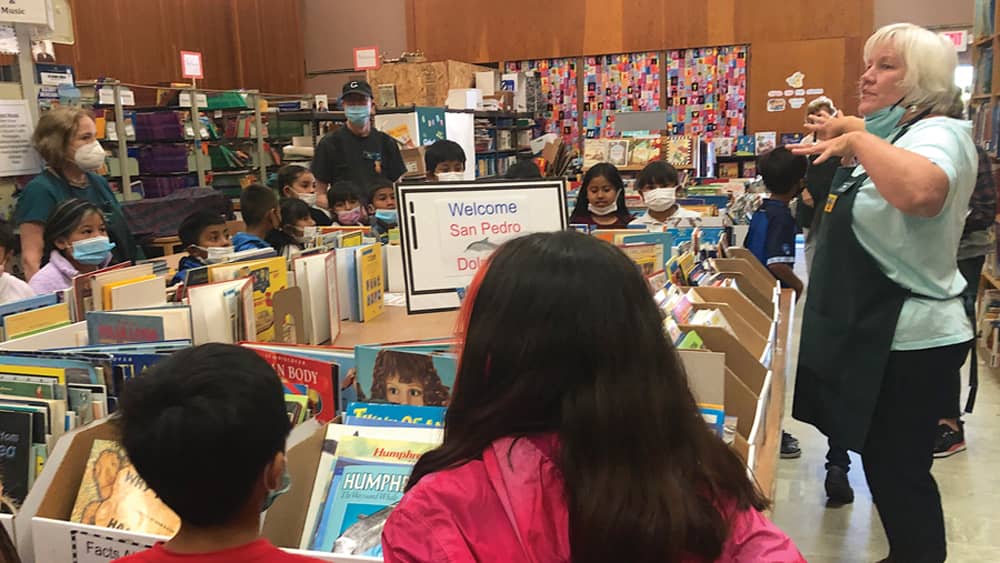

The Global Book Exchange began in 1987, when former teacher Marilyn Nemzer decided to collect used books in good condition and give them to teachers who needed resources for their classrooms, but had limited budgets. The first giveaway was on the driveway of her Tiburon home, and since then it’s distributed more than 1 million books both locally and abroad.

Today, the Global Exchange is located in the gym of a former elementary school in San Rafael, and it welcomes children in grades two through eight from Marin County’s Title 1 schools—those that receive federal funds to support low-income children who qualify for free or reduced-cost lunches—on literacy field trips. On arrival, every student receives a bag to fill with up to 10 books of their choice to read at home. Topics range from dogs and dinosaurs to Harry Potter and how to make paper airplanes. Local Rotary clubs underwrite the cost of the field trips, and in the 2021-22 academic year, 1,600 children and 75 teachers visited from seven schools and chose more than 15,000 books. Teachers, who each filled a box with books for their classroom libraries, report that many of their students have few, if any, books at home, and the opportunity is life-changing.

Books also go to classrooms and libraries with empty shelves, nonprofits that serve children, needy families, schools recovering from disasters and people learning English. The goals are to support learning and literacy worldwide and save good books from landfills. “We so much appreciate the donations of new and gently used books we receive from the Marin community. Our volunteers often have tears in their eyes seeing how truly excited the students are as they carefully select their books, one by one, knowing those books will be theirs to keep,” says Nemzer. The Global Book Exchange, a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization, depends on donations and is open to the public on Wednesday and Saturday. For hours and more information, visit bookexchangemarin.org.