Bread has been an important and ubiquitous food staple for thousands of years. You likely can’t remember not having bread on your family’s dinner table while growing up––maybe not at every meal, but at most. The simple blend of flour, water and yeast has evolved through the millennia, but these basic ingredients have changed little in our lifetimes.

“Bread” is synonymous with “money” in our culture. That makes sense, because ancient Egyptians once used bread as currency––such was its importance in daily commerce at one time. And many eons ago, “breaking bread” became a popular expression for sharing a meal.

Our hunger for bread shows no signs of waning––it’s estimated that the average American consumes 53 pounds of bread in a year, according to one university study. Statista says Americans eat whole wheat and multi-grain breads most often (more than 192 million of us annually), followed by white bread, Italian bread and French bread.

Bread’s influence in our everyday culture and society can’t be matched by any other food, which explains why there are thousands of bakeries in the United States, including the 122-year-old Franco American Bakery on the edge of downtown Santa Rosa.

“My father, Robert Bastoni, was the second generation to run Franco American Bakery,” says Kristin Bastoni-Frazee, president and CEO of the bakery located on West Seventh Street near Santa Rosa’s Railroad Square. “He had so much knowledge and love for the business that he was truly the best inspiration I could have asked for.”

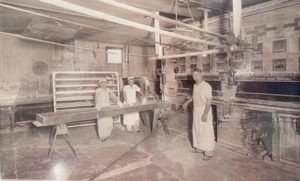

Founded in 1900, the bakery had been owned and operated by the Bastoni family since 1938, beginning with Bastoni-Frazee’s grandfather, Mario, and his brother, Frank. In 1965, Robert Bastoni joined his father and uncle at the bakery. Robert launched his career at the bakery by driving a bread delivery truck around Sonoma County, helping fill in for employees on vacation and handling the sales side of the business. Eventually, he became more involved in running the whole operation.

Older property, older building

Bastoni-Frazee is the youngest granddaughter of Mario Bastoni. There was never much doubt in her mind that she would one day take over operations at Franco American. “I started working there every Saturday when I was 13. When I got my driver’s license, I worked about three days a week after school and on Saturdays. Then I went to Empire College and earned a business certificate. I’ve been full-time at the bakery since I was 19, so going on about 33 years.”

Robert passed away in September 2021 at the age of 78, and since then she has operated the bakery in ways she feels would make him proud. “I wear all the hats here now,” she says.

The bakery has seen many changes over the years. The original building was once two stories, but the top story burned down in the 1950s. Instead of rebuilding the top floor, it was decided to expand the lower level. In the 1960s Franco American purchased two city lots west of the bakery to create more production and parking space. Later, in 2000, two more lots were purchased south of the bakery.

“We have an older property and an older building, but it works for us,” says Bastoni-Frazee. Today the bakery itself is about 15,000 square feet, and a retail store onsite is open several days a week. “We have many customers who come nearly every day to get a loaf of bread. Just about everything we make is available in the store,” she adds.

Currently the bakery employs 36 (including Bastoni-Frazee) and makes 120 different baked goods from six types of dough: sour, sweet, wheat, brioche, potato and rye. The bakery generates about $5 million in annual revenue and produces 1.2 million units of bread in a typical year. “A loaf is considered one unit, as is a bag of buns or rolls,” says Bastoni-Frazee. Most of Franco American’s products are consumed within Sonoma County; nine delivery trucks cover nine routes in a territory bordered by Bodega Bay, Cloverdale, Kenwood and Petaluma. “I also sell to independent distributors who buy our bread directly from us and deliver it to Ukiah, Lake County and also Novato,” she says.

The bakery is a 24/7 operation, though “technically we are only open five days a week,” says Bastoni-Frazee. “But there’s always someone here every day.” The bakers bake ahead for the following day, starting around 1 a.m. “And then it’s a 26-hour process to make one day’s worth of bread. Our drivers come in between 2 and 3:30 p.m. every day to load their trucks and begin deliveries,” says Bastoni-Frazee. This schedule rarely deviates, because the bread and the customers won’t wait.

“The biggest drawback of owning a bakery is that it runs 24/7, so my phone will ring at all hours of the day and night,” she adds.

Running the business old-school

After World War II ended, Mario and Frank Bastoni heard about a huge, unused state-of-the-art oven still in its crate at Fort Ord in Monterey County. They bought it, installed it in the bakery, and increased production from making 160 loaves at a time to more than 240 loaves at a time. The oven was only recently taken out of service after a run of about 75 years. “It was falling apart and the wiring was going bad,” says Bastoni-Frazee. “It was starting to be a hazard. One of the smartest moves I’ve made is upgrading to more efficient ovens and reinvesting money back into the company.”

The bakery used to get its flour from a General Mills mill in Vallejo, which closed long ago because it needed millions of dollars in upgrades, says Harry Stuart, an account executive for General Mills and longtime vendor and friend of the Bastoni family. “Robert was concerned that General Mills might let me go [when the mill closed], but it all worked out fine. I’ve been working with Franco American for almost 29 years. They really care about people.”

Bastoni-Frazee says her father worried that with the shuttering of the Vallejo mill, Stuart would lose a lot of business and General Mills wouldn’t need him anymore. “So we started buying General Mills Gold Medal Wheat-a-Laxa flour from Harry. We have to buy a semi-truck load at a time, and each load lasts us about five months. We used to buy it from a distributor and only ordered what we needed for a week at a time. For many years after the Vallejo mill closed, we ordered our flour from Pendleton Flour out of Idaho, which was shipped by rail. Now we get most of our flour from Miller Milling out of Oakland––a weekly delivery of 50,000 pounds.”

Stuart says Robert Bastoni was a man of his word, and his daughter Kristin is no different. “You don’t find that too often in business anymore,” he says. “The Bastoni family makes a good product and offers good service. They are one of the few customers I’ve never had a problem with. They know how to run a business, and they do it old-school. Whenever I stopped by the bakery, Robert would always tell the staff to ‘give Harry whatever he wants.’”

Robert was also a mechanical wizard who could fix anything, adds Stuart. “He’d save old equipment parts to reuse them. They tried to save money anywhere they could.”

The old Italian clan

Robert Bastoni was also a creature of habit. “He came into my restaurant every morning at 9 sharp for a cup of coffee,” explains Roger Praplan, chef and owner of LaGare French restaurant in Railroad Square. It was a tradition that began with Roger’s father, Marco, who founded the restaurant.

After Roger Praplan took over the restaurant, the morning coffee tradition continued. “Robert would pour himself a cup, stay about eight minutes just to chat and then take off. And he didn’t like me being late. He had keys to the restaurant so he could make bread deliveries. If I was late for coffee in the morning he’d be waiting at the door, having already let himself in and started the coffee. And I had keys to the bakery in case I needed some bread urgently, especially if we were having a big Saturday night of 250 diners and in danger of running out. We don’t like to waste bread so we don’t over-order.”

Robert was part of “that old Italian clan,” says Praplan, that operated many businesses downtown. “There was the old Michelle’s restaurant [now Starks Steakhouse] and Lena’s restaurant [now Chop’s Teen Club]. Those may be history but the bakery is still going strong. A lot of people don’t realize that you have to bake bread at night because the dough has to rise the day before. Robert would go down to the bakery at 3 a.m. just to be with his crew.”

Praplan was a pallbearer at Robert Bastoni’s funeral, and “I was quite honored to do it.”

Bastoni-Frazee says her grandfather Mario would rarely patronize a restaurant that didn’t serve Franco American bread, believing that if they weren’t a customer, you just didn’t eat there. “So if he did go to a restaurant that wasn’t one of our customers, he’d bring his own bread in his pockets, pull it out and place it on the table. Needless to say, when I laid to rest both my grandfather and father, they had bread in their pockets.”

Open-door policy

The fourth generation of the Bastoni family is now on the job at the bakery, with the addition of Bastoni-Frazee’s daughter, Ashley, 22, who is also working toward her bachelor’s degree in business. “I learned everything here at the bakery through the years, and I’m trying to pass all that knowledge along to Ashley. She’s already trying to take some of my work from me,” her mother adds with a laugh.

Giving away and donating bread to good causes is also a Bastoni family tradition. “My father had a big, generous heart,” says Bastoni-Frazee. “When friends and family came into the bakery, he always loaded them up with bags of bread. We never had fresh bread at our own house because he gave it to our neighbors.”

More recently, during catastrophic wildfires, Franco American Bakery donated bread by the truckloads to feed evacuees and first responders. “We reached out to all the companies we knew were trying to feed fire crews and people who were displaced,” says Bastoni-Frazee. “We took many loads of bread to the Veterans Memorial building and the county fairgrounds where meal preparations were going on. And whenever Guy Fieri does any local big feeds for fire victims, firefighters and others, such as health-care workers during the pandemic, we try to donate to his causes.”

Bastoni-Frazee says she has no plans to step away from the business yet. “I don’t know if that’s good or bad. My father worked until the day he died, but eventually I’d like to enjoy my retirement. This has always been a small family business, and I take it to heart. All of the people who work here are like my children, and I love it. I have an open-door policy, always, and I’ve worked by butt off for so many years to get to this point. Still, I miss my father every day and wish I could talk to him.”

Baking Bread Through the Decades

1900 – Franco American Bakery is founded in its current location at 202 W. Seventh St., Santa Rosa

1928 – Mario Bastoni begins working at the bakery

1938 – Mario and his brother Frank purchase the bakery

1960s – two city lots to the west of the bakery’s location are purchased to help with expansion

1965 – Robert Bastoni, one of Mario’s sons, begins working for the bakery; Robert’s cousins Frank Jr. and Stephen Bastoni, sons of Frank Bastoni, also begin working at the bakery during the 1960s

1985 – Kristin Bastoni, Robert’s daughter, begins working at the bakery on Saturdays at the age of 13

1991 – Kristin joins the bakery full-time to assist her father, Robert

1997 – Franco American Bakery takes over the Mezzaluna bread line from local restaurateur Michael Hirschberg

2000 – two city lots to the south of the bakery are purchased for further expansion

2000 – Mario Bastoni passes away

Early 2000s – Frank Jr. and Stephen Bastoni retire from the bakery

2008 – Robert purchases the bakery from his cousins Frank Jr. and Stephen

2021 – Robert Bastoni passes away, and Kristin Bastoni assumes leadership of the bakery

2022 – Kristin’s daughter Ashley, the fourth generation of Bastonis to own and operate the bakery, joins the company

Mystique of the Mother Dough

During the pandemic, many locked-down Americans picked up a new hobby: making sourdough bread. Packaged yeast was scarce for many months from upheavals in supply chains, but because sourdough ferments its own yeast, home bakers were naturally drawn to the challenge.

The science behind sourdough includes words like “lactobacilli,” but essentially the bread has a tangy or sour taste that’s produced from gas bubbles and lactic acid created by the lactobacilli. Franco American Bakery’s “mother dough” is more than 100 years old, “fed” daily to produce the loaves of sourdough bread it is famous for.

“Mother dough is considered the sponge, which is just flour and water,” explains Kristin Bastoni-Frazee, president of the bakery. “We feed it daily by adding more flour and water to it, and then it sets again in refrigeration to ferment. The amounts of water and flour that are added daily depend on how much of the starter was used by the bakers on a given day and how much starter is left. But we keep feeding that dough until it ferments. If we don’t feed it, it will go bad, and it’s kept refrigerated to prevent spoilage.”

The age of a bakery’s sourdough starter can be a point of pride. Franco American’s mother dough passed the century mark many years ago, and Boudin Bakery in San Francisco claims it has used the same sourdough starter for more than 150 years.

Bread’s Global and Local Economic Impact

Bread is one of the oldest foods consumed by most cultures around the planet. Its early beginning dates back 30,000 years; by 10,000 B.C. grains had become the main ingredient for making bread. Wheat was first domesticated in the Middle East thousands of years ago, and today wheat is grown on more land area throughout the world than any other food crop, according to the United Nations’ Statistics Division. In 2020, production of wheat worldwide reached 1.7 trillion pounds.

All of that wheat supplies thousands of bakeries in hundreds of nations, including 23,158 retail bakeries in the United States––3,400 of them in California. The American Bakers Association reports that the baking industry has more than 800,000 skilled workers in the U.S., accounting for an overall economic impact of more than $154 billion. In California, the economic impact is nearly $16 billion, and the industry employs approximately 86,000 workers statewide.