Marin County has long had a reputation for liberal viewpoints and progressive ideas. And yet, when the Othering and Belonging Institute at the University of California Berkeley studied population distribution for a study in 2018, the results showed that Marin is one of the most racially segregated counties in the San Francisco Bay Area. The predominance of Whites in many of the county’s neighborhoods is easy to observe, but the reasons for such clearly defined segregation are less well known.

Now, though, the Marin County Restrictive Covenant Project is raising awareness of the disparity and its origin, as it seeks to find and redact language and conditions—aka “restrictive covenants”—in property deeds that prevented people of color from purchasing, renting or occupying homes in many areas of the county for a lengthy stretch of the 20th century.

The presence of racist language in restrictive covenants locally first came to the attention of county officials in 2017, when Marin’s 2nd District Supervisor Katie Rice discovered wording she found offensive in her own property deed. “Katie Rice was the first one,” says Jodi Olson, Marin County chief deputy recorder-county clerk. “It was the first restrictive covenant modification that we recorded.”

The change to Rice’s deed came at her own request. But in September 2021, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed AB 1466 to address such discriminatory restrictions. The bill became law in January 2022 and requires each of California’s 58 county recorders to modify all property deeds with discriminatory passages. The goal is to find the deeds, create redacted versions and record the new documents as official public records. “The original document stays intact,” says Olson, explaining that a “restrictive covenant modification” references the original document, which remains unchanged, thus preserving the historic record.

The arc of the covenants

Restrictive covenants are common in property deeds and are usually found in the Declaration of Covenants, Conditions and Restrictions that a homeowners association uses to define its rules. An HOA might require homeowners to adhere to a specific color palette when painting their homes, limit the height of fences or prohibit large dogs, for instance. The restrictive covenants that are the focus of the project, however, are the result of government policies that made financing for the building of new homes dependent on limiting ownership to Whites.

As Olson explains, between 1926 and 1948, Marin County was becoming less rural and more suburban, and many homes were built with racist restrictive covenants—ostensibly for financing purposes.

A U.S. Supreme Court decision made racial limitations in restrictive covenants legal in 1926, and they became widespread after the creation of the Federal Housing Administration in 1934. The FHA insured bank mortgages with coverage that was 80% of the purchase price; the FHA also did its own appraisals. Among its standards was a Whites-only requirement, essentially mandating segregation in the belief that non-White owners would be at risk of default and would lower property values. In addition, after World War II, the Veterans Administration began guaranteeing mortgages for people who had served in the military services, and it adopted FHA housing policies, thus excluding Black veterans. Insurance from the VA and FHA provided insurance for entire subdivisions during the post-war building boom of the 1950s and 1960s and, as a result, the new neighborhoods were exclusively White.

In 1948, Shelley v. Kraemer, a lawsuit that attempted to prevent a Black family in Missouri from taking possession of a home they had bought without knowing they were prohibited from ownership, reached the Supreme Court. The high court ruled that banning home sales to people who weren’t Caucasian violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The FHA subsequently announced it would no longer insure properties with race-based restrictive covenants, but the agency was resistant to altering its standards and found ways to avoid complying with the ruling. More meaningful change came in 1962, when President John F. Kennedy issued an executive order that prohibited using federal funds to support discrimination, forcing the FHA to stop providing insurance to subdivision developers if they refused to sell to Black buyers. Then in 1968, Congress passed the Fair Housing Act, officially prohibiting housing discrimination and rendering race-based restrictive covenants illegal once and for all. Yet the original language of previously established race-based restrictive covenants remained in countless property deeds.

AB 1466 requires the recorder’s office in every county to produce a plan for finding and modifying documents with racist language by July 2022. Olson, who has spent 27 years in the Marin Assessor-Recorder-County Clerk’s office and was previously an appraiser, took the lead and created Marin’s plan with oversight from Shelly Scott, the county’s assessor-recorder-county clerk. The legislation allows county recorders to add $1 to every recording fee to cover costs, but Marin’s office decided not to do it at this time. “That was Shelly (Scott)’s decision,” Olson says. “It felt kind of wrong.”

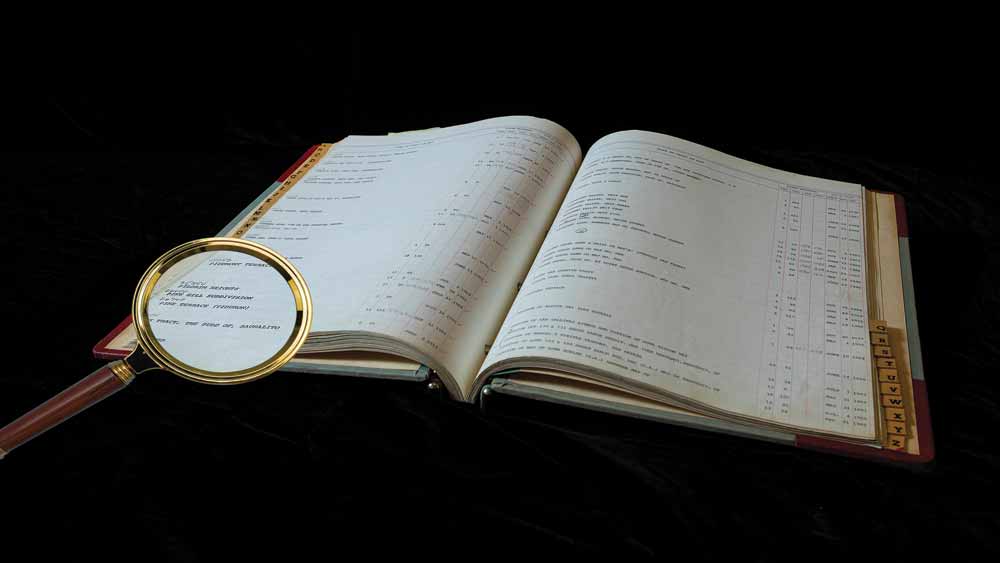

The Big Book of Subdivisions

Finding parcels with deeds that need modification is a slow, analytical process, in which four staff members of the recorder’s office use their discretionary time to work on the project. They’ve found 7,200 parcels with restrictive covenants so far, and the starting point was a large, decades-old book her office found containing an index of Marin’s parcel and subdivision names—in some cases specifically referencing a property’s covenants. “This book was a gift of gold,” says Olson, explaining that modern, digitized county records are indexed and searchable by name of buyer/seller. The old bound volume, however, can be searched by address and parcel number—making it easier to find restrictive covenants if you know which neighborhoods are more likely to have them.

Deeds in need of redaction are the easiest to find if they’re in subdivisions, which often have homeowners association bylaws. She gives Strawberry, an unincorporated area near Mill Valley, as an example. “I knew it would be common in that neighborhood; it has several subdivisions,” she says. In contrast, rural properties, such as those in West Marin, are challenging because they often have legal descriptions that make them difficult to identify. “We don’t have the expertise to locate properties with complicated descriptions,” she says, and so a retired land surveyor is helping to pinpoint them. In some other cases, parcels were combined, and the identifying numbers changed, leading to mismatches, so they’re also difficult to find.

“Not all counties have taken this in quite as much depth as we have,” says Olson, but she believes it’s important to do a thorough job. She explains that the documents are organized by parcel, not address, and the work started with a big Excel spreadsheet, which provided an orderly system for compiling information. In addition, the team taped together maps to show entire areas. The project also includes a time-progression map on its website, which shows when and where houses with restrictive covenants were built in Marin. (Find it at marincounty.org/main/restrictive-covenants-project)

“It makes people see that it happened here,” she says, adding that the structural discrimination had a profound impact on residents who were prevented from buying houses. “People who should have been able to build wealth through property ownership were left behind. Think of the equity they could have built. It left a lasting negative,” she says, observing that home ownership could have helped their kids go to college and made retirement easier.

Housing discrimination reverberates today

Liz Darby, social equity programs and policy coordinator for the Marin County Community Development Agency, explains that AB 1466 requires counties to look at how past housing policies have impacted populations, particularly those disproportionately affected by them. “These policies continue to have an impact today,” she says. “The law has been taken off the books, but if you look at demographics, it still has negative impacts.” She gives the placement of supermarkets and quality of schools as examples. Marin City and San Rafael’s Canal neighborhood are Marin County’s most segregated neighborhoods, and neither has a fully stocked supermarket, limiting options for shopping without leaving the community. School districts in affluent communities, which are predominantly White, get their funding from property taxes, which gives them substantial revenue, allowing them to provide extra resources for their students. Less-affluent districts rely on funding from the state based on average daily attendance, giving them less revenue and preventing them from offering their students the same advantages and opportunities.

“Everything needs to be looked at with a strategic approach. … We’re planning for the future,” Darby says, explaining that examining how past housing policies have affected different populations shows the impact housing discrimination has had, and the knowledge can be an influence in determining how to create housing policies in the future.

One can’t change the past, but Darby believes it’s possible to educate people and inform them about Marin’s history of housing discrimination, while telling them how it relates to the current housing element. “To this day, it’s still a surprise to discover that people don’t know about housing discrimination. I get excited when people are bored because they’ve heard it before,” Darby says.

She credits Supervisor Rice for pushing the topic forward. “Her owning this role and taking it on and ensuring that the county continues to utilize this program to educate and inform has been critical in allowing the work.”

Segregation Central: Marin City

Darby learned the history of housing discrimination from residents of Marin City, an unincorporated area between Sausalito and Mill Valley that was developed in 1942 as a federal housing project for workers building ships at Sausalito’s Marinship during World War II. It was an integrated community until the post-war years, when White workers were able to buy houses in other parts of the county, while Black residents, lacking the same opportunity, had to stay behind. Hearing their stories helped Darby understand the injustice, but she observes that many people still do not know the history.

Marin City resident Felecia Gaston, a founder of the Marin City Historical and Preservation Society, has been collecting the community’s history for 30 years. She’s recorded oral histories and heard many of the stories firsthand, and she explains that people wanted to buy homes outside of Marin City to give their children and grandchildren betters lives but were robbed of the opportunity. She recalls a couple who considered buying a house in Mill Valley, but when they went to see the house, a group of White neighbors was waiting and made it clear they weren’t welcome. They returned to Marin City. She also recalls a couple who wanted to view a house in Tam Valley and was permitted to look at the exterior but wasn’t allowed inside. Unable to overcome the obstacles, some Black residents left the county to buy homes, and some purchased pole houses—homes on stilts made from telephone poles—in Marin City. Most, though, gave up the dream of home ownership. “It’s important that the county is making this recognition,” Gaston says, but she adds that while a few Marin City residents are aware of the project, it hasn’t moved the needle. With the increased cost of real estate, “They still won’t be able to buy a home in Marin County.”

Passing the story to the next generation

Two years ago, Crystal Martinez and Nancy Vernon, aides to Supervisor Rice, began to look for ways to address past housing discrimination. Among the initiatives, they created a special high-school intern team to determine what the project might mean to young people.

Shyla Lensing, currently a senior at Redwood High School in Larkspur, had done racial justice work at school and founded the Redwood Women of Color Club. “I really wanted to learn about the roots of where we live,” she says, observing that properties all around the school had restrictive covenants. And so she became an intern with Supervisor Rice’s office. She and another member of the team started by going to the California Room at the library in the Marin Civic Center, where they searched through clippings and decades-old posters looking for evidence of racist language. They analyzed everything from a restrictive-covenant viewpoint and amassed the information on a huge spreadsheet. Then, after conducting extensive research, they started looking for ways to incorporate their new knowledge into the curriculum of local high schools—that’s when they met Fatima Hansia, a social studies teacher at Marin’s Community School, an alternative public school which shares grounds with the Marin County Office of Education in San Rafael.

“A lot of time we learn about race and discrimination; we’re told that it exists,” says Lensing, but “[Hansia’s] curriculum shows how discrimination exists in Marin County. She has [students] go through various resources and do research to come to that conclusion themselves.”

Hansia learned about the restrictive covenants project in early 2022 when she created and taught a unit to her students investigating how segregation affects residents of Marin County. She and a group of student interns later became involved with the project when she was teaching at the Marin County Juvenile Hall last summer. Her students are in seventh through 12th grades, and they tend to come from marginalized communities and have different lived experiences than those attending mainstream high schools. “The system has failed them,” she says. “I wanted to create something that was relevant and empowering for them.” She guides students to discover for themselves how systemic policies and attitudes have prevented people of color from climbing up the socioeconomic ladder, using a curriculum she has created based on project-based learning, allowing them to see the data, analyze it and draw their own conclusions. In one activity, they use real-estate search engine Zillow to make comparisons and look at the difference between housing prices in Sausalito and Marin City. Students investigate how the historically repressive legacy of the government’s redlining policies still has an impact on Main City’s real estate value. In another, they read the Marin County Human Development Report 2012, where they can see that life expectancy is lower in segregated communities. That leads to a discussion about the health gap and its causes, and students read short paragraphs and answer questions. Then they focus on the community of their choice and look at different indicators, such as the availability of healthcare facilities and the location of fast-food restaurants. Finally, they visit the neighborhoods to take pictures so they can create a photo essay.

Hansia shared her curriculum with the interns and advised them on how to frame a pitch so they could suggest it to other teachers. She’s pleased to share her work with other educators and says, “I think it’s important to teach this curriculum. Where you live affects your opportunities. This is an opportunity for teachers and students to investigate why it is this way. Segregation was purposefully done by design. It’s empowerment to be aware of the conditions of your own communities and lead change.”

Lensing worked at the Freedom School in Marin City last summer and had the chance to see the community that was impacted the most by racist restrictive covenants. “It was interesting being in a part of Marin that’s often been ignored,” she says, adding that it made her want to share the history with others to find out how we can bridge the gap in the future. “I’m so incredibly grateful and inspired by all the adults who have led this project so far,” she says. “It’s incredible to be part of this project.”

Vernon reports that the interns said they’d never drive along Highway 101 through Marin County again without thinking about the history. “I think the youth voice makes a huge difference,” she says. Students get a lot of traction with adults as well as peers. When you see a younger generation, they get it and want something better.”

“We can’t move forward without knowing where we came from,” adds Martinez, who observes that Marin County is a perfect case study. “Lack of access to housing created a big divide here.

“A house is not just a house—it’s possibility. It changes people’s lives.”

Olson doesn’t know how long the Restrictive Covenants Project will take, because regular work for the recorder’s office comes first. Nonetheless, the project is moving forward, and its value was reflected by a recent special recognition. In December 2022, the California State Association of Counties honored Marin’s Office of the Assessor-Recorder-County Clerk with a Challenge Award for the Restrictive Covenant Project. “I’m very proud of it,” says Olson. “I’m so lucky to be involved in a community that’s engaged in this.”

The project is a major step in redressing a historic injustice, but racism still exists in Marin County. As a person of color and as someone who grew up in the county, Hansia finds Marin a difficult place to live, and she reports that her students experience racist incidents often. However, people shy away from talking about it, so open discussion and learning from the past is important.

Darby, meanwhile, says the most important thing is to continue telling “this story”—and she encourages others to join her.

“It’s person to person, community to community,” says Darby. “It’s the voices of Marin County.”

No praise for appraisal

In Marin City, fair housing is still an aspirational concept.

At least that’s what Marin City homeowners Paul Austin and his wife Tenisha Tate-Austin discovered in 2020, when their mortgage broker hired Miller and Perotti Real Estate Appraisals to value their home as part of a planned refinance. When MPREA returned with an appraisal of $995,000—$455,000 lower than the home’s 2019 appraised value—Paul and Tenisha, who are Black, smelled a rat. So the couple asked their broker to schedule a second appraisal with a different firm—this time with a White friend welcoming the appraiser to the home, where they removed photos, art and other personal family items. That appraisal came back at $1,482,500—nearly half a million more than the first.

The feeling of being lowballed on the base of their race was “overwhelming” Paul Austin told the Marin Independent Journal. Confident their situation was a violation of fair-housing law, the couple partnered with Fair Housing Advocates of Northern California in a civil suit against MPREA, along with AMC Links, the appraisal management company which hired Miller’s firm, alleging housing discrimination.

In March, the plaintiffs reached a confidential settlement with AMC Links, in which the company “denied any wrongdoing,” and also came to a settlement agreement with MPREA for an “undisclosed monetary amount” and a promise it will not “engage in any form of unlawful discrimination in the appraisal of residential real estate” going forward.

Perspective

After discovering the restrictive covenant in the deed for her property in San Anselmo, Marin County Supervisor Katie Rice read The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, by Richard Rothstein, an authority on housing policy who explains how restrictive covenants were national policy implemented at local levels. “Discriminatory housing policies of the past, such as racially restrictive covenants and redlining, have had a cascading effect that carries through to today,” she says. “Not only were they mechanisms of residential segregation, they also laid the foundation for the building of generational wealth for some, generational poverty for others. “I believe awareness and understanding of the history of housing discrimination in our communities is critical to informing housing policy that supports affordability and inclusivity going forward. The restrictive covenants project has been an incredibly powerful tool in growing that awareness and understanding at the community level.”

The language of discrimination

Restrictive covenants contained specific language such as the following to prohibit the sale or rental of property to certain members of the population.

“…hereafter no part of said property or any portion thereof shall be…occupied by any person not of the Caucasian race, it being intended hereby to restrict the use of said property … against occupancy as owners or tenants of any portion of said property for resident or other purposes by people of the Negro or Mongolian race.”

Source: Marin Restrictive Covenant Project

How to get involved

The Marin County Restrictive Covenant Project welcomes the participation of Marin residents and offers several ways to get involved.

- Resource HUB: Members of the community can share their experiences with restrictive covenants and their impact.

- Education. The Marin County Free Library offers books, articles and videos that allow people to learn more about racially restrictive housing programs in Marin and the entire country.

- Participate now. Learn how to modify racially restrictive covenants in property documents, and see a map of currently identified locations with racially restrictive covenants in Marin County.

- Shape the future. Check out the Housing Element, a planning process to identify how to meet housing needs at all levels, which is currently underway.

- Design a participatory budgeting project. Propose a project to the Office of Equity Participatory Budgeting Committee that addresses the effect of racially restrictive covenants in Marin County. Projects that are accepted will receive $50,000 to $250,000 to implement the project.

- Become an intern. High school and college students can assist with research, school pilot programs and community outreach. For more information, contact Crystal Martinez at cmartinez@marincounty.org.

- Modify a document. A Restrictive Covenant Form allows a property owner to identify illegal language in a deed and asked to have it removed. Find out how by going to the website or calling the Recorder’s office, 415-473-6093.

Source: Marin County Restrictive Covenant Project