Plans for the future of the Sonoma Developmental Center campus have been in discussion since the facility closed in 2018.

Perhaps no proposed housing and development project in Sonoma County has necessitated so much scrutiny and planning––while at the same time ruffling feathers and causing ill will––than the site of the 945-acre former Sonoma Developmental Center at Glen Ellen, closed since 2018.

Five years after the Sonoma Developmental Center (SDC) was shuttered by the state—and following three years of community meetings, hearings and discussions with advisory bodies—the County of Sonoma last December approved its Specific Plan for how the SDC site should be reimagined for housing and other uses. The county also certified an extensive environmental impact report (EIR) for the vast property that had been released two months earlier.

SDC is owned by the State of California and overseen by the Department of General Services, which has spent more than $10 million a year to keep it from falling further into disrepair, but the County of Sonoma was tasked with coming up with a development plan that would work best with the scale of the property and take into consideration the many concerns of neighbors and other stakeholders: traffic and water impacts, wildfire risks and evacuation routes, and preservation of a large wildlife corridor that passes through the site.

“Essentially, the state created a unique relationship with the county to let the county set the rules and what can be developed, and to come up with a plan that makes sense and works for the area, provided we protected the open space, prioritized housing and had an economically feasible plan” explains Bradley Dunn, a policy manager for Permit Sonoma, the planning department for the county. “It’s one of the largest housing developments currently planned in Sonoma County and, obviously, is very important for the future of the area.”

$100 million to fix infrastructure

Whoever is selected by the state to buy the site will decide how to develop the site, adds Dunn, as long as it follows the restrictions of the county’s adopted Specific Plan.

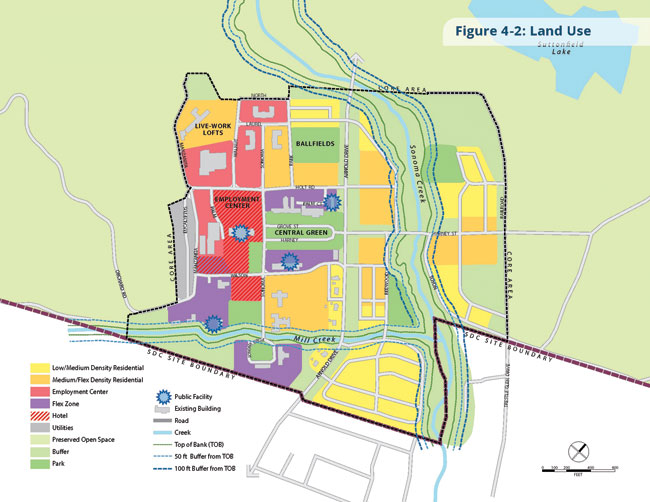

Some of the main points of the county’s Specific Plan includes the approval of open space protection for 700 acres; a base of 620 housing units subject to the county’s affordable housing program; the potential for creation of more than 900 jobs; a walkable core with transit, pedestrian and bike paths as alternatives to automobile use; and institutional uses focusing on research and education that would drive employment. For instance, last September the California Coastal Conservancy approved a grant of up to $250,000 for the county to explore the creation of a Climate Adaptation Center at the site. According to a statement released by the county in December, “the Specific Plan adopted by the Board of Supervisors includes flex and other zoning that could be used by the Coastal Conservancy for such a center.”

The Specific Plan, says Dunn, includes a lot of smart measures, such as housing aimed at what the real estate industry calls the “missing middle”––essential workers like teachers, nurses and firefighters. The housing is really designed for these people, he adds, “who can’t afford to live in Sonoma Valley but don’t qualify for low-income housing.”

At least $100 million will be needed to repair the aging infrastructure on the site and bring it up to code before a developer could even begin building, says Dunn. You can’t expect a developer to build a project at a loss, and the answer can’t always be ‘build housing someplace else.’”

A time-consuming process

The Sonoma Developmental Center had a checkered past. When it first opened in 1883 it had already been located near Vallejo for a time, as well as in Alameda County and also in Santa Clara for a few years. It was originally named the California Home for the Care and Training of Feeble Minded Children, later shortened to the Sonoma State Home and then the Sonoma State Hospital, providing services to people with developmental disabilities.

Operated by the State of California, it opened on Arnold Drive in 1891, and had as many as 3,000 residents and staff living on the site when it was an active facility. Its name was changed to the Sonoma Developmental Center in 1986, and at one time it was the county’s largest employer. In its early years the center freely performed sterilizations [see sidebar], while other abuses such as assaults and drug overdoses were reported in more recent decades.

Still, people living near the property are passionate about it, says Susan Gorin, the county supervisor who represents the 1st District, where SDC is located. “They embrace advocacy and ownership of the center. Family members over multiple generations had worked and lived there. They continue to hike the trails and walk the grounds, and they want to protect this beautiful and peaceful environment. I understand why they were not happy with the Specific Plan as it moved forward, because the proposed development was out of scale compared to the kind of rural development around the center.”

Gorin said the county had conversations with the Department of General Services after SDC was closed in 2018, and the state told us that the county would have five years to plan for redevelopment of the site. “But five years is a very short timespan for transitioning a very complex site,” she says. “The state didn’t realize how time-consuming this would be. And look what we’ve been through in five years––fires and other disruptions such as COVID-19––yet we still had to adhere to the state’s timeline. Meanwhile, the cost of construction has gone through the roof, particularly when you need to create defensible space and use fire-resistant building materials to ensure that everyone on the campus and around it will be safe in the next fire.”

Proposed hotel has few fans

One concern frequently brought up is how water will be provided for the new housing and other occupants on the redeveloped site. “There is adequate water on the site, and the site has valuable water rights to go along with potential new development,” says Gorin. “There are two reservoirs on the site that have been used to manage water, and there will be a way to accommodate that through water agencies. Sonoma Water is using a minimal amount of water on the site now, but all of the water and sewer lines have to be replaced. It’s all one unified campus similar to the Presidio in San Francisco.”

She prefers a concept that’s very different. “There will be no space for a golf course or a swimming pool, so it can’t be a resort. Instead, we need to think about a small boutique hotel that could be opened in the existing iconic brick building, which will be expensive to rehabilitate. It could serve as a small conference center for employers on the site.”

Sonoma Mayor Sandra Lowe is in agreement with Gorin about the hotel proposal. “Don’t get me wrong, I love hotels and I want more of them, but to put up a tony hotel in a place that once dealt with some of the most vulnerable people in the state just doesn’t seem like the right thing to do,” she says. “If it were a small retreat-style conference center, I would see that as appropriate for the area. I’m also in favor of a climate center on the site, which would benefit the world and provide something of an economic engine for a different type of employment. My issue is that whatever is put there should be like what we had before in terms of employment opportunities––jobs that paid a living wage, and included health benefits and a secure retirement.”

In addition, the matter of preserving the open space should take into account how long SDC has been closed, says Gorin. “Sonoma Land Trust, Sonoma Ecology Center and the Sonoma Mountain Preservation Group have been studying this, because the campus has been essentially vacant for five years. So the wildlife have developed different behaviors from before, when it was a functional center.” The property is part of a wildlife corridor that links Sonoma Mountain to the west to the Mayacamas mountains to the east.

Lawsuit challenges EIR

Not everyone is happy with the county’s development plan and environmental impact report. Two groups based in Sonoma Valley––Sonoma Community Advocates for a Livable Environment (SCALE) and Sonoma County Tomorrow––filed a lawsuit in January challenging the EIR [see sidebar].

“The existing EIR was done too rapidly for a development of this scale,” says Tracy Salcedo, a Glen Ellen resident and spokesperson for the two groups. “So the foundational elements are either nonexistent or not based in reality. There were a number of things not analyzed well, and we would want the county to look again at all those things to use real on-the-ground data. It’s better to do it right.”

One example of the EIR’s shortcomings, says Salcedo, is the fire evacuation plan. “A development the size of what is proposed basically means doubling the population of Glen Ellen, and our previous evacuations left a mark on everyone, we were all traumatized, and we know that fire will happen again.”

Salcedo, whose own property borders the north edge of the SDC property, says her main motivation is making certain that the open space is preserved. “And preserved in such a way that it stays healthy. We call Glen Ellen ‘where Sonoma Valley goes wild.’ There’s a lot of open space areas here that are all interconnected.”

The groups are also asking that the proposed housing on the site be built first, before any other construction begins. “We are all for affordable housing, it’s important, and we have never said no to that. But a developer could put up a hotel first and other buildings for commercial uses, and then the housing seems secondary. We just believe the housing should be the first thing built.”

Gorin wasn’t surprised a lawsuit was filed to challenge the EIR. “The county, state and the interested developers knew that this effort could result in lawsuits, so they were prepared for it. It didn’t catch anyone by surprise. The next step is for the state to select the development team, and there might be delays as this lawsuit moves forward. But we are working to resolve the litigation. We will work through this.”

In the meantime, Gorin would like to see some immediate uses of the site as a way to generate revenue, “because it will take a while to get the buildings retrofitted and rehabbed.”

Creativity required

While Mayor Lowe believes parts of the county plan may have merit, she said important considerations still need to be addressed, such as preserving and repurposing the campus’s historic buildings, and “preserving the history of the people who lived and died there.”

“There is something magical about the place,” she continues. “It’s a legacy piece of the environment and history of our state. I encourage people to go walk there because when you do you will sort of understand why people feel so passionate about the next steps.”

Gorin is optimistic that the development plans for SDC will ultimately be a major step forward for Sonoma Valley. “But building anything on this campus will require creativity,” she says. “It won’t be a cookie-cutter anything.”

Lawsuit Threatens to Stall Plans for SDC

As frequently happens with proposed large-scale projects in environmentally-sensitive areas, a lawsuit has been filed challenging the plans for redeveloping Sonoma Developmental Center in Glen Ellen. Two community groups are critical of the environmental impact report (EIR) prepared by Sonoma County for the site, stating that the EIR doesn’t address the problems associated with the center’s rural location, wildfire vulnerability, water supply, limited roadways and biologic and historic resources, among other issues.

Sonoma County Tomorrow and Sonoma Community Advocates for a Livable Environment (SCALE)––the two plaintiffs in the lawsuit, which was filed in January––referred to the EIR as “a short-sighted plan with serious environmental consequences.” On its website, SCALE also states that it opposes the county’s Specific Plan for the SDC as being “out of step with neighboring communities, the most acute housing needs in the area, and the need to enable mitigation of wildfire risk and retention of evacuation capacity from wildfires across an already limited rural transportation system. This environmentally sensitive, historically important and culturally significant landscape deserves better than business as usual.”

Bradley Dunn, a project manager with Permit Sonoma, shared a statement released by the county in February: “The SCALE case is a lawsuit alleging noncompliance with the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) in regards to the county’s approval of the SDC Specific Plan and certification of the associated environmental impact report in December. The SDC Specific Plan was adopted to govern future uses and development following the state’s expected disposition of the property. The plan prioritizes open space and wildlife protection, housing development and economic sustainability. The county conducted extensive environmental analysis of the proposed project and takes its obligation to comply with CEQA seriously. To date, the county has not been served with the petition.”

Sterilization Survivors Urged to Seek Compensation

To reach victims of forced sterilization at state hospitals––including at Sonoma Developmental Center––and in state prisons, the California Victim Compensation Board began broadcasting radio and TV spots in January to encourage them to step forward and apply for compensation. As many as 5,500 male and female residents of SDC underwent vasectomies or salpingectomies (removal of the fallopian tubes), primarily between 1909 and 1952. It’s believed that almost 600 survivors of state-sponsored sterilization are still living, as many underwent the procedures when they were very young.

The practice of sterilization among people who were identified as developmentally disabled—and subject to such one-time clinical (but now pejorative) labels as “morons” or “imbeciles”—was common during those years at facilities where the developmentally disabled were confined, and many of the procedures were performed without the person’s consent, at the behest of some medical and administrative leaders who believed they should not be allowed to procreate.

The Forced or Involuntary Sterilization Compensation Program, which began on Jan. 1, 2022, concludes this year on Dec. 31. The program is intended to compensate survivors of these procedures that took place as a result of scientifically discredited—and morally abhorrent—eugenics laws that existed at the time. Eugenics laws were repealed more than 40 years ago.

Approximately $4.5 million has been allocated to be split among all eligible survivors who apply. To learn more, visit victims.ca.gov.

Author

-

Jean Doppenberg is a lifelong journalist and the author of three guidebooks to Wine Country.

View all posts