Americans have been foraging foods from the wilds for longer than they have been harvesting foods they planted and grew. Foraging is still alive and well today and the North Bay

is blessed with an abundance of wild foods. Locals harvest wild foods from the woods, meadows and waterways, including the ocean and coastline.

There are even businesses that incorporate wild harvested foods into their products. We spoke with three such North Bay entrepreneurs who are using the age-old practice of foraging for their businesses. All of them spoke of their love of foraging, as well as their commitment to doing it right and not causing harm to the areas they’re harvesting from.

Putting the ‘fun’ in fungi

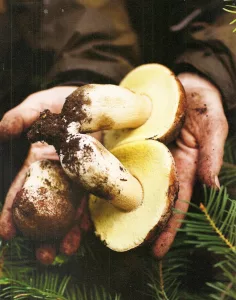

Connie Green, owner of Wine Forest, a wild-foods wholesaler in Napa, has been foraging since she was a child and says she loves being out in nature harvesting mushrooms. She started selling them in 1981 and is still going strong.

“I still pick mushrooms because it’s what brought me to the dance, and that’s what I love,” she says. “We’re the oldest remaining wild mushroom company in the country—the real pioneers of this, really.”

Wine Forest sells packages online—wineforest.com—of dried mushrooms like porcini, black trumpet, candy cap, wild lobster, yellow foot, chanterelle, morel, grey morel and mousseron. They also sell products that incorporate mushrooms, truffles, shrubs and nuts. They have photos and clear descriptions to help identify edible mushrooms, instructions on how to clean and dry them as well as recipes for mushroom dishes.

Green has written a book along with co-author Sarah Scott called The Wild Table, Seasonal Foraged Food and Recipes. Although the book was a labor of love, she says it was also hard to simply sit for that long to work on it. She would rather be out in the fresh air moving about and harvesting wild things.

Green feels as though she gets to bring that breath of fresh air along with her mushrooms to local chefs who are in their kitchens all day. She says she especially loves working with chefs at the many North Bay restaurants she sells her mushrooms to.

“I have a teaching degree and people have certainly wanted me to take [book] tours and do all of that when my book came out,” she says. “But I really like dealing with the food people.”

“I’m focused on mushrooms because this can be done without hurting anything—I mean plants are another story,” she says. “Mushrooms, these things are utterly sustainable, so I feel happy and very comfortable with that.”

Green says one of the most rewarding things about foraging is returning to the same “patches” over a long period of time.

“I really love having a very long, many years in my case, relationship with a particular part of the woods,” she says. “When I’m harvesting stuff, I get the long view. Every year it

changes a little bit. I’m utterly vested in its preservation, and the intimacy of that is very precious to me.”

Green has been harvesting from the same oak trees for over 40 years. She recalls years when no mushrooms grew due to lack of rain. “There was a year where the entire chanterelle season, I picked 3 pounds. And then there’s been other chanterelle seasons in which I’ve picked 4,000 pounds—and it’s completely related to climate.”

Green says the mushrooms are dependent on the health of the trees. “As long as the tree hasn’t been killed by a fire then, depending on the species, they can go on and on and on,” she says. “[Mushrooms] have a long-term marriage with various trees and if rainfall changes quite dramatically or if we start getting extreme cold—it is going to be a problem.”

Green says she’s worried about how climate factors might impact the places she’s been harvesting from for all these years. “We’re worried about extreme fires, because when habitat is destroyed by extra-hot fires, you’re going to have to wait 50 years until the trees grow back,” she says.

Green says the pandemic impacted her sales quite a bit because 80% of her business is to restaurants. “We just hunkered down and got through it and came out the other side,” she says.

The other 20% of her business is to grocery stores and she’s hoping she can increase that demand. “One of my fondest wishes is for people to use more dried mushrooms because this is still a bit exotic for most American households,” she says. “I’m pretty dedicated to trying to make that less exotic and more of a comfortable use as it is in Europe.”

Seaweed sourcing

Heidi Herrmann is helping others get comfortable with wild harvesting seaweed along the Sonoma Coast. She says she likes feeling accountable for her food. She wild harvests seaweed and sells it through her Santa Rosa business, Strong Arm Farm, and teaches others how to harvest the nutrient-rich, high-protein food.

Herrmann says harvesting seaweed is a lot of fun and she enjoys the entire process of foraging, rinsing and drying it.

She was growing vegetables and flowers at Strong Arm Farm when she decided to bring along some dried seaweed to her farmers market table. “It was so well received,” she says. “The chefs were excited and there was no [sales] competition, so there was a real niche.” That was 2009 and she’s still the only commercial seaweed harvester in Sonoma County.

She says it was a lot more fun than growing and competing for carrot and onion sales, so she stopped selling vegetables entirely and focused on seaweed.

Herrmann is a member of the faculty at Sonoma State University and Santa Rosa Junior College and the seaweed harvest fits in perfectly with the academic year.

“The harvest is done primarily in June and July when the tides are lowest and I get the best access to these shore varieties,” she says. “It’s hot out, so the seaweed can dry easily.”

Herrmann wild harvests five different kinds of seaweed. She says kombu is the most popular and the most abundant. She also harvests nori, bladderwrack, wakame and a little bit of sea palm.

She’s wild harvesting in shallow water. “You can just wear rain boots and go in between the tide pools and collect it,” she says.

She says she goes out with a small group of about five people on her business harvest days. “We descend onto the beach and we’ll have a little base camp there,” she says. “I just use kitchen or office scissors to harvest the seaweed and each blade is cut one by one.”

“I explain how to cut and where to cut so it can regrow,” she says. “Then we go out and usually it’s an hour before and an hour after the low tide moment. We’ll collect maybe 100 to 150 pounds of wet material and then lug that back up to the truck. I bring it inland and rinse it all and then lay it out on screens to dry.”

Herrmann says harvesting seaweed is a sustainable activity—but that knowing how to cut and when to cut is crucial. When approaching a harvest area at the beach she begins assessing its quality and abundance. She said if she finds it looks as though it’s in decline it may not be appropriate to harvest from that area.

She says the populations have been pretty steady in the last 15 years she’s been collecting.

Herrmann’s wild harvesting is in the jurisdiction of the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. She has a license from DFW, a permit for each year she’s commercially harvesting and she pays a small fee per pound for her harvests.

Seaweed sales took a big dive right at the beginning of the pandemic; the majority of her clients are fine restaurants in the Bay Area and corporate campuses. “They truly bought, like, the lion’s share and so when all those went to zero there was a bit of a panic,” she says.

“The chefs still don’t have big budgets. It’s not what it used to be like pre-pandemic,” she says.

But then the home cooks got busy, and her smaller retail package of seaweed took off. “Sales went crazy,” she says. Also the home-delivery service Good Eggs began selling her seaweed and it’s helped to keep the business afloat.

Strong Arm Farm products can be purchased from its website (strongarmfarm.com) and at several Petaluma locations, including the Petaluma Seed Bank, Jupiter Foods and Bodega Oyster Co. They’re also served by restaurants like The Nectary and Valette, both in Healdsburg, and Crisp in Napa.

Herrmann leads classes in wild harvesting seaweed along the Sonoma Coast through ForageSF. “There’s actually 640 different kinds of seaweed down there, so we first have to find the four or five that are in the culinary trade,” she says.

Herrmann includes concepts around ethical harvesting in her classes. “There’s the local indigenous people’s kind of tradition around this food that’s about being mindful of the role it plays in the ecosystem that we’ve just popped into,” she says.

She explains that seaweed is actually a keystone food for a lot of species. “It’s the food source for everything that lives in that intertidal space, like sea urchins, starfish and birds,” she says. “I even see deer hooves down there and raccoon paws and otter. There’s a lot of species that rely on these seaweeds.”

From chef to harvester

Maria Clementi took one of Herrmann’s classes and says that Herrmann has since become her mentor. Clementi is a chef and incorporates wild-harvested seaweeds into her culinary creations for her Marin-based business, DoorYard Provisions.

Clementi had been working as a chef in a restaurant when the pandemic hit and when everything shut down, she decided to strike out on her own. “I had a couple of different things that I was doing just for fun and when I put them all together, they were like a line of food,” she says.

She began selling her products in local outdoor markets in late 2020 and now is focused on being a private chef and caterer as well as selling her products online—Dooryardprovisions.com —and in retail shops.

She sells things like Sesame Toasted Nori, Wild Seaweed Bullion, Curly Kale Chips, assorted dried seaweeds, spices and teas from her website. She also sells her products at Solstice Mercantile in Fairfax, the West Marin Culture Shop in Point Reyes and plans to have her Wild Elderberry Immunity Tonic at the Tierra Vegetable Farm Stand in Santa Rosa.

She’s very committed to operating in an ecologically sustainable way and is consciously creating a business that reflects those strong ethics. “The last thing I want to do is have a negative effect,” she says.

She uses organic ingredients and likes to support other small businesses and local farmers when sourcing them. She also changes her offerings with the seasons and likes to introduce her customers to less-common seasonal flavors like wild plums and quince.

After taking the class with Herrmann she began incorporating wild-harvested seaweed in her line of food products and cooking. Like Herrmann she is very keen on environmental ethics. She harvests alone from two coves and only takes what she can carry out.

“When I run out of my stash of seaweed, I purchase from Heidi—so that’s a really cool way to keep it all in the family,” she says.

She also forages for other wild foods like nettles, wild plums and even acorns for making acorn flour.

She even wild harvests fennel pollen. “It’s actually a lot easier than you would think for something that is known as being so expensive and, you know, fancy,” she says. “But essentially, you snip the head of the blooming fennel flower off, and you keep it in a paper bag and let it dry. And then you just shake the pollen off as it dries.”

She does a bit of gleaning too, which is similar to foraging but is defined as a gathering of items after a main harvest. She says the gleaned items are often coming from neighbors who have more than they can use from their trees or gardens.

Clementi says she likes encouraging others to consider what is growing around them, to learn about them and to not be afraid to try incorporating them into their food. She says that it’s a great way to connect with nature and to live more sustainably.

In the end, Connie Green says that anyone can wild harvest sustainable products if they look hard enough.

“When they become important to you, you become vested,” says Green. “And the well-being of that natural environment goes up miles in your heart, your mind, your sense of responsibility for preserving it. It’s kind of a wonderful thing.”