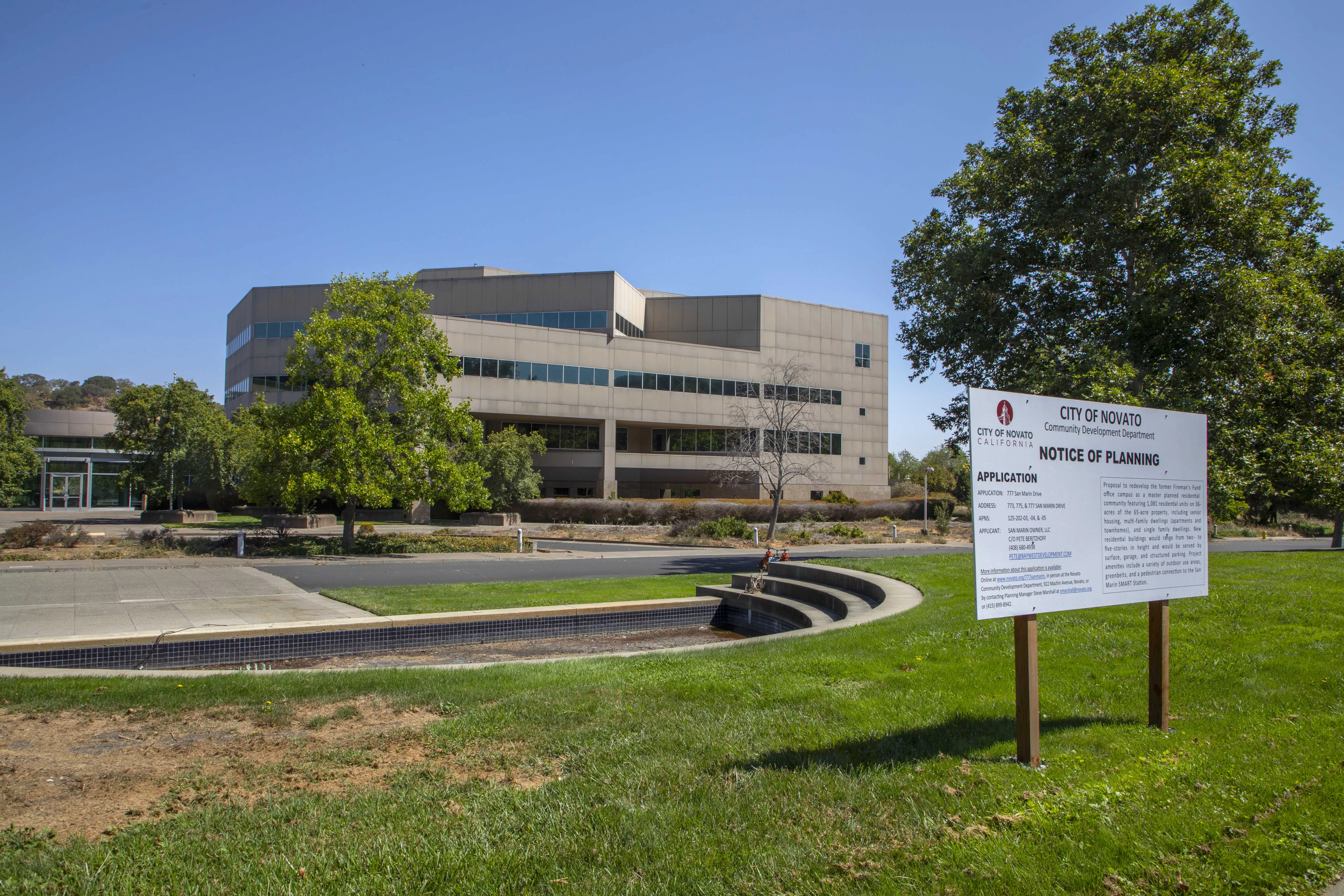

The 63-acre Fireman's Fund campus at 777 San Marin Drive in Novato was once home to Marin's largest employer. The property has been vacant since 2015. [Photos by Duncan Garrett Photography]

Nobody embraces recycling like Marin. On a weekly basis our bins overflow with paper, plastic and glass. Reusing and reutilizing is in the county’s DNA, tucked neatly between a love of animals and adoration of high home-resale values. Marin has always given a deep tree hug to Mom Earth. And now, thanks to cultural changes, regulations, old-fashioned economics and real-estate cycles, office buildings and retail centers may join wine bottles, junk mail and cardboard as a recycling focus.

That cardboard in our bins demonstrates another trend driving real-estate-use changes as Marin consumers punch laptops and cell phones the way some shoppers used to walk through malls.

Amazon and eBay and digital cousins like macys.com and even costco.com have become destination shopping. So, while Marin has a dozen malls and shopping centers, there is at least one that has seen the future—and it looks a lot like housing. Hello Northgate Mall.

On the office building side of commercial real estate, there is of course the Fireman’s Fund campus. The 63-acre Fireman’s Fund property—briefly rebranded as North Bay Crossing—is slated for recycling as housing with very limited retail if property owners Bay West Development and Forum Investment Group have their way. A 10-point plan to build 1,100 apartments, townhomes, senior housing units and houses is currently in Novato’s planning process, which is another way of saying grab some snacks and settle in on the couch, it’s gonna be a while.

With Marin’s dedication to open space and careful deliberation toward development, fresh building on virgin soil has been a rare bird. Rather, Marinites have grown accustomed to new building springing up where old structures had outgrown their usefulness, the redevelopment of Fourth Street in San Rafael where Macy’s used to sell perfume is a good example. Though the process has been known as redevelopment, it now has a new handle—recycling—and is part of a nationwide trend.

Creative use of language and renaming things has a glorious history where real estate is concerned. Cottages the size of a postage stamp aren’t small, they are cozy. Homes just this side of a teardown are rustic. Affordable housing became workforce housing because affordable housing had become a bogeyman with myths tied to crime and unemployment. Here in liberal Marin, the affordable-to-workforce transition hasn’t made much difference in terms of acceptance, the Not In My Back Yard crowd still holds too much sway in slowing down progress.

In New York City’s financial district, five different office buildings are getting a residential redo. A building that was formerly home to bank JP Morgan Chase is currently slated to be the new location of 1,300 apartments, the largest such project in the country.

Just as redevelopment has become recycling, the discussion about recycling office and retail has been eased by more vocabulary additions. Zombies used to be stars of bad movies where the dead came back to life, but now they are pretty much vacant properties, like say Fireman’s Fund.

It’s easy to point to urban areas like NYC, Los Angeles and our neighbor to the north San Francisco, and say this is a metropolitan issue. But nationally there are no shortage of suburban malls that don’t see the kind of foot traffic they enjoyed in in the past—and vacancies are prevalent.

In Southern California’s Westminster Mall, a recycling is taking place where 3,000 residential units are coming online along with 425 hotel rooms. The Laguna Hills Mall is adding office space, hotel, 1,500 housing units and limited retail space.

Peter Calthorpe, the father of the New Urbanism movement and a Sausalito resident, has long advocated for transportation-linked development with more density and more respect for the environment. He led the study for transportation and land use to bring passenger rail back to the North Bay, the precursor to the SMART train. His latest hook is the recycling of strip malls across the country for housing. It isn’t that suddenly Calthorpe’s passion is a brilliant concept (though Calthorpe is certainly a thinker of the first level), it’s that there are so many more candidates.

Mask-up kids

COVID took a toll in many ways—and one of the most obvious is the office. Corporate warriors used to trade tales of brutal commutes, surviving mind-numbing miles, scattered road-rage incidents and burns from spilled coffee in order to sit through meetings that should have been an email. Dodging boring colleagues was elevated to an art. And knowing which elevator was the fastest was a guarded secret.

But that all got switched out for those working at home. Zoom no longer means going someplace fast, it means going no place at all—in some cases spinning your wheels, but doing it with lots of faces on a computer screen. Commutes on the ferry were exchanged for walking from the bedroom to your home office in your jammies. A stop at Peet’s was traded in for a cup from Keurigville. “Showering if you want to, brushing your teeth if you want to,” was the way Bob Eyler, econ professor at Sonoma State and columnist for this magazine, described the more relaxed at-home vibe.

Eyler has taken a hard look at the shift in who goes to the office and what it could mean for the local economy—and it has an interesting angle. According to Eyler, the COVID-forced work-from-home shift tipped the scales between labor and management as people have remained productive and now have grown more at home at home. He says a shrinking work force has given labor leverage even as management begins flexing muscle about employees coming back to Cubicle City. Eyler also adds that the general labor market is seeing more push back from unions as Hollywood locked horns with writers and the automakers found their industry up on a lift as workers said no go. Unions are now edging back into fashion.

He also came up with a unique take for Marin: So, if your company says you can work from home, who says your home needs to be in Marin? He thinks we could see some Marin residents taking money off the table, selling their homes and living and working someplace less expensive, which could alter the basic demographic in the county.

In a general way, Eyler sees the shift toward online retail as a net negative—“unless you have an Amazon distribution center locally.”

When it comes to office space in Marin, Haden Ongaro is a mover and a shaker. An executive managing director at commercial real-estate company Newmark, Ongaro has some insights into the shifting market. Vacancies in Marin are higher post-COVID, 19% vs. 15%, which makes sense given a shift in some workers hanging at home. But the 19% figure isn’t very far out of line for where office space has hovered for about a decade, Ongaro says.

While Northgate and the Fireman’s Fund campus are the high-profile examples, there are things behind the scenes happening, as well. Ongaro says there are properties on Fourth Street in San Rafael that are being acquired and assembled with a plan to eventually build housing, with mixed use on the ground floor.

If this rings a bell it’s what we saw on Fourth Street with the old Macy’s, which closed its location near the corner of A Street in the mid-1990s, was demolished and rebuilt with retail, offices, apartments and an open plaza. At the time the project was eased via a lengthy process led by the city where residents and merchants, the stakeholders, were quizzed on what they wanted to see downtown and how change might make the downtown area more vibrant.

At the time I wrote a piece for the Pacific Sun saying you could fire a cannon down Fourth Street and not worry about injuries. I caught some flack about it not because it wasn’t true, but because I had the bad taste to point it out in print. After the projects were completed and traffic became challenging, I queried an elected city official about the complaints from residents that now downtown was too busy.

He smiled and nodded. “Yeah, that’s a bitch.”

Ongaro says that reuse of office for housing could be easier than you might think. In Marin, many retail areas are zoned for use in housing as well, making the process easier for those developers wanting to join the recycling trend.

Another thing working in favor of shifting office to housing is that elected officials now understand that housing is arguably the most important issue facing cities and towns in Marin, Ongaro says. With new laws in place, local governments need to provide honest opportunities for developers to add housing, and the laws have teeth.

But Ongaro also points out that shifting from office to housing might not deliver a project that will appeal to the public. “Renovating office for housing may require more density than people want to live in,” he says.

Another problem is that costs to demolish and prepare a site for housing may be too high and make projects too expensive for the market.

Finally, Ongaro argues that saying there is too much office in Marin might not be accurate, and that succeeding cycles might demand new office be built.

You better shop around

Shopping centers with big name retailers and trendy downtown boutiques share a common enemy as consumers embrace the digital age and free shipping—forsaking brick-and-mortar retailers in favor of having a first name relationship with UPS drivers who know your canines so well they carry dog biscuits. According to the U.S. Commerce Department, 15.4% of all retail business in the U.S. was done online in the second quarter of 2023. That includes grocery shopping, so the number is more impressive than at first blush.

Still, there are certain items that seem like definite in-person buys. Shoes for one, I mean your dogs need to feel good in the new kicks, right? You can’t check the fit online. Tell that to Zappos and Shoes.com.

Beds. Surely one must hop in the car and drive to Mattress Firm, and lay ones head on a pillow. Find out if that pillowtop is actually pillow soft. Perhaps have a little pillow talk with a sales associate. Unless one wishes to surf brands like Saatva, Leesa and Nectar and embrace free shipping.

I spend my day parked in front of my laptop, writing sentences and searching for the truth; Google is my homey. But I’m a rookie compared to my wife, who furnished most of a 2,200-square-foot house online after we spent too many years in a condo the size of a bathmat. The old furniture landed in my office and is comfy if not stylish. But the house needed a dining room table, chairs, a couch, an island, sideboard, desks, beds, chests, lamps and nightstands. The list went on and on.

She got it done with style and efficiency. I love her. So does Amazon.

My point is, there are changes going on that not only impact our economy, they impact existing real estate and how we view and use it for the future.

Between working from home and increasing digital shopping, commercial real estate is in flux. Office buildings have higher vacancy rates and malls and downtowns are seeing retail spaces staying empty longer. With all the talk in Marin of thinking globally, and shopping locally (code for honoring downtown boutiques), a fair number of locals can still be found crowding the aisles at Costco on weekends, buying vats of mayo, standing in line waiting for the rotisserie chickens to be ready and throwing nasty elbows while scooping up samples of Super Extra Large Peanuts.

The state is in the act as well—as Sacramento tells cities, towns and counties how much new housing jurisdictions need to assure can be built to accommodate future populations, even as Marin sees an outflow of residents.

Put that all together and you have a brand new category of commercial real estate: Recycled and Reimagined.

Retail blues

On a recent November afternoon, the Northgate Mall could have passed for almost any shopping center in Marin. Shoppers carrying their bags fumbled for the keys to their SUVs while other drivers waited semi-patiently for them to cross in front. Christmas was certainly in the air inside the mall even if it wasn’t in the hearts of those doing battle for better parking.

But Northgate isn’t like any other shopping center in the land of organic milk and small-batch raw unfiltered honey. While Northgate boasts traditional retailers like Macy’s and Kohl’s, and even has made-in-Marin retailer RH Outlet, the mall has a vacancy rate of 11.4%, according to LoopNet, because it has one foot in the past and the other in the future.

Constructed in 1965 and refreshed from time to time, Northgate had anchors that included Sears and Mervyn’s and at one time was owned and operated by Macerich, mall retail royalty. Macerich still owns The Village at Corte Madera, the top retail draw in the county.

Perhaps retail managers aren’t worried about the digital invasion. Corte Madera Town Center General Manager Monty Stephens says that his mall is always adding new merchants and eateries to the mix. He also says that shoppers still want the in-person experience of “touching and feeling clothes before buying them and trying on makeup,” and of course you can’t get that sort of sensory experience from the Amazon app.

With the holiday season upon us, and retail centers full of both cars and people, it’s harder to imagine some of those same centers being reused for housing. But that could be the wave of the future.

As to the office life and the prospect of jam-packed office buildings in Marin, it’s hard to imagine employees who can do the job at home, making the choice to jump back in the car, boat or bus, and lead the cubicle existence. On the other hand, when They Who Must Be Obeyed says your paycheck depends on your smiling face gracing the office on a regular basis, maybe your neighbor’s weekly assault on the senses via an orchestra of leaf blowers and weed whackers is just enough to bring you back to elevatorville.

Out of Office

Fresh rumors about a possible bankruptcy of WeWork sent shockwaves around the commercial real estate market last week, leaving office landlords around the world trembling with fear at the prospect of losing one of their largest tenants. Especially in prime markets such as New York City, San Francisco, London and Paris, WeWork played an outsized role in the office rental market, occupying large swaths of premium office space.

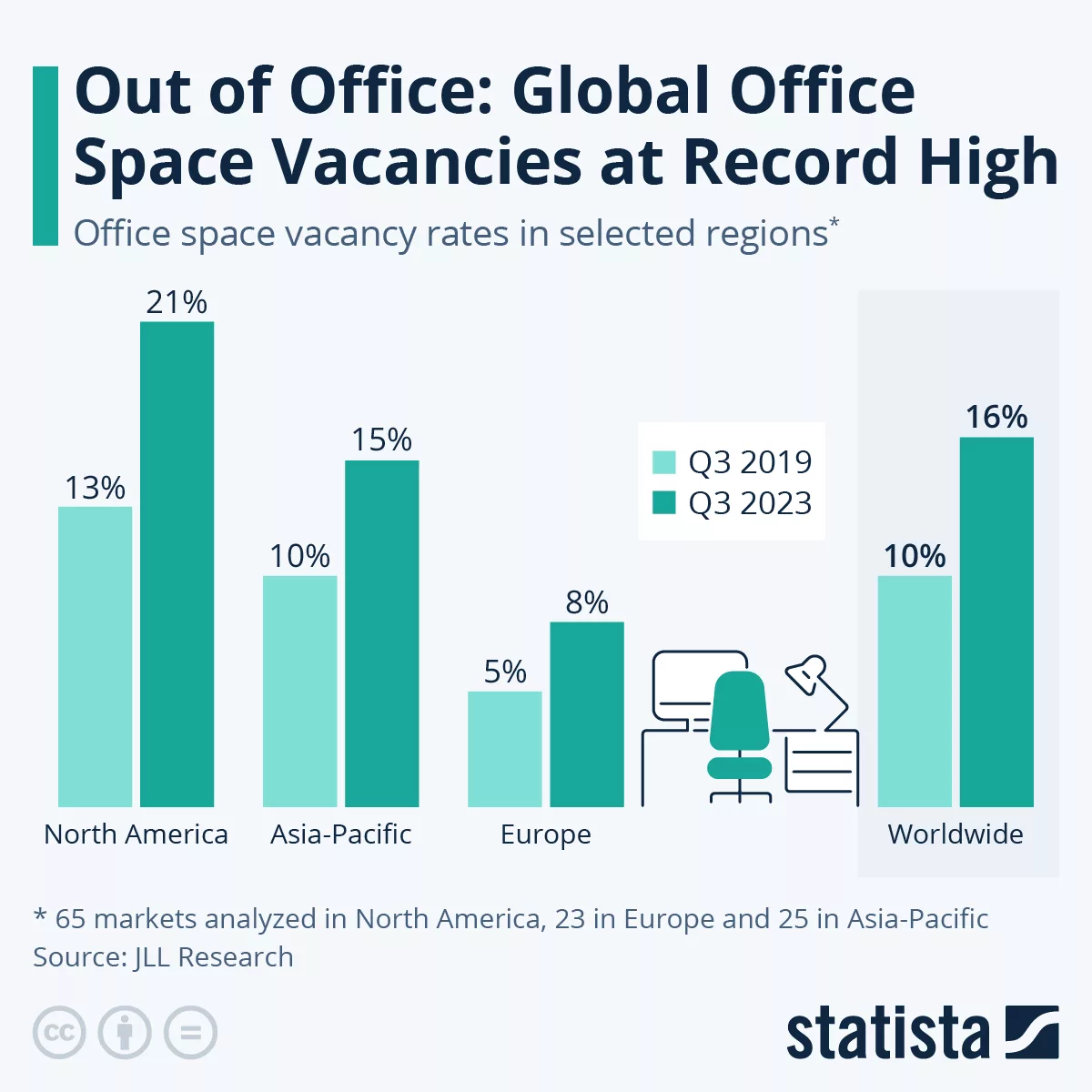

The reports of WeWork’s imminent demise come at the worst possible time for landlords, who are already struggling to find tenants, as many companies are reducing their office footprint to reduce costs and adapt to the post-pandemic world of hybrid work. According to real estate specialist Jones Lang LaSalle (JLL), office vacancy rates are higher than ever, reaching 21% in the U.S. and Canada in Q3 2023 and 16% globally, i.e. in the 100-plus markets analyzed by JLL Research. In both cases, that’s an increase of 60% compared to pre-pandemic vacancy rates, which stood at 13% and 10% in North America and globally in Q3 2019, respectively.

At the end of June, WeWork operated 906,000 workstations in 777 locations across 39 countries, with total (current and long-term) lease obligations amounting to $14.2 billion. While it’s unclear what will happen to these locations in case of bankruptcy, landlords look certain to lose out on a large chunk of their agreed-upon leases and to end up with even more excess supply of prime office space.—Felix Richter

Author

-

Bill Meagher is a contributing editor at NorthBay biz magazine. He is also a senior editor for The Deal, a Manhattan-based digital financial news outlet where he covers alternative investment, micro and smallcap equity finance, and the intersection of cannabis and institutional investment. He also does investigative reporting. He can be reached with news tips and legal threats at bmeagher@northbaybiz.com.

View all posts