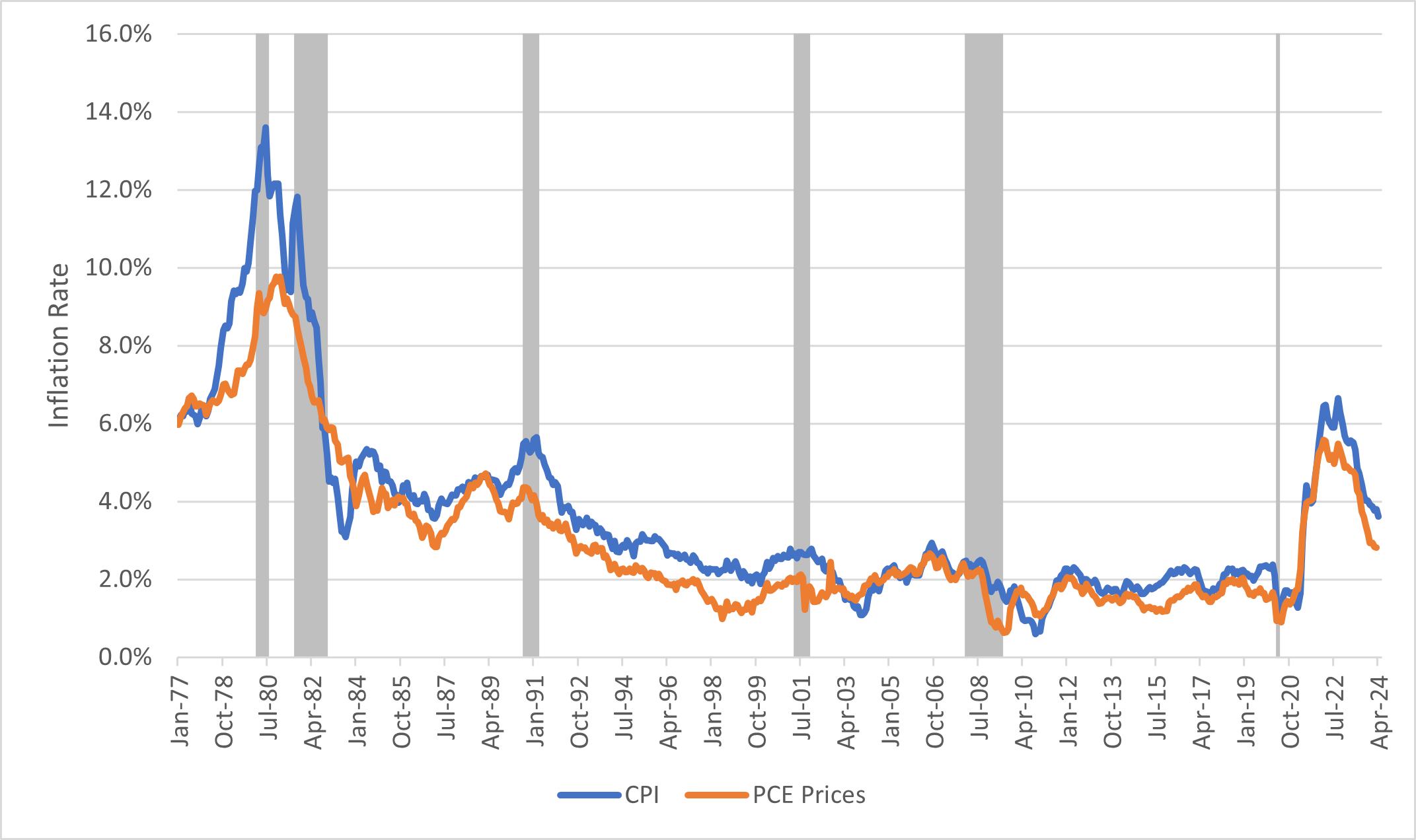

CPI and PCE Prices, Core, Percentage Change (Annualized Inflation Rate) from 12 Months Ago, 1977-2024, United States, Shaded Areas = Recession Source: FRED Database St. Louis Federal Reserve

Inflation is one of the most watched data points in every economy. Some measure of inflation is part of many labor contracts throughout the United States, such as keeping up with the “cost of living” as it changes. Generally, to track inflation we watch the Consumer Price Index (CPI). This familiar sampling of goods and services households buy comes from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) due to its connection to so many labor contracts. Another measure of prices and changes over time is the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) Price Index. This price index is meant to be comprehensive and not a sample of what we buy at home monthly. It comes from tracking American spending on consumer goods and services (including housing) and tracking the difference spent in terms of quantity of goods versus prices. The change in prices is a change in personal consumption expenditures.

Policymakers tend to watch PCE prices (in Europe, there is an analog known as the “Harmonized” Index of Consumer Prices, or HICP) because it is more comprehensive and is more tied to measures such as gross domestic product than the CPI sampling method. Trying to guess how policymakers, such as the Federal Reserve or European Central Bank, will change policy based on new inflation data is a fool’s errand unless legal guidelines exist. In Europe, precedent, law and treaties suggest any new data on inflation above 2% or 2.25% annualized inflation (how much goods and services have changed in price from 12 months ago) means interest rates will increase; data below those thresholds may or may not mean interest rates would fall.

To further complicate matters, policymakers and economists tend to reduce the number of goods and services by removing food and energy from the consumer basket, which is called “core” prices. I get a lot of questions about why core is used. The simple answer is that there are many times in history where the outbreak of war, a natural disaster or a bad harvest can trigger a commodities-market shock to prices that will not last due to the supply chain bouncing back or demand receding from the immediate need. Hence, changing interest rates due to perceived—and short-lived—inflation is considered short-sighted.

The accompanying data shows how correlated the American CPI and PCE price index are to each other. The data is from January 1977 to April 2024. Recessions over that time are shaded. Notice that there are subtle increases in both inflation rates when getting closer to a recession and then a movement down after recession begins (and sometimes after the recession ends). Inflation is generally a coincident (same time as) indicator of recessions rather than a leading indicator. However, changes in inflation expectations by consumers can change their behavior now and can lead to recessions or at least slower growth in economies.

Inflation is a function of excess demand in markets. Inflation surged in 2021—with lingering effects as of spring 2024—due to a combination of demand rising from government spending rising (fiscal stimulus) and lower interest rates and supply-chain contractions globally. Relief has come, but interest rate relief may take longer. Next time, we will look at inflation expectations, their role in bond markets, and what monetary policymakers are really trying to do when fighting inflation by raising interest rates or keeping them at relatively high levels.