North Bay wineries and wine grape growers are exploring adopting remotely operated vineyard robots, a shift that could reduce the number of human workers. The change means labor unions like United Farm Workers are increasing their interest in developing technology training for workers and addressing potential layoffs.

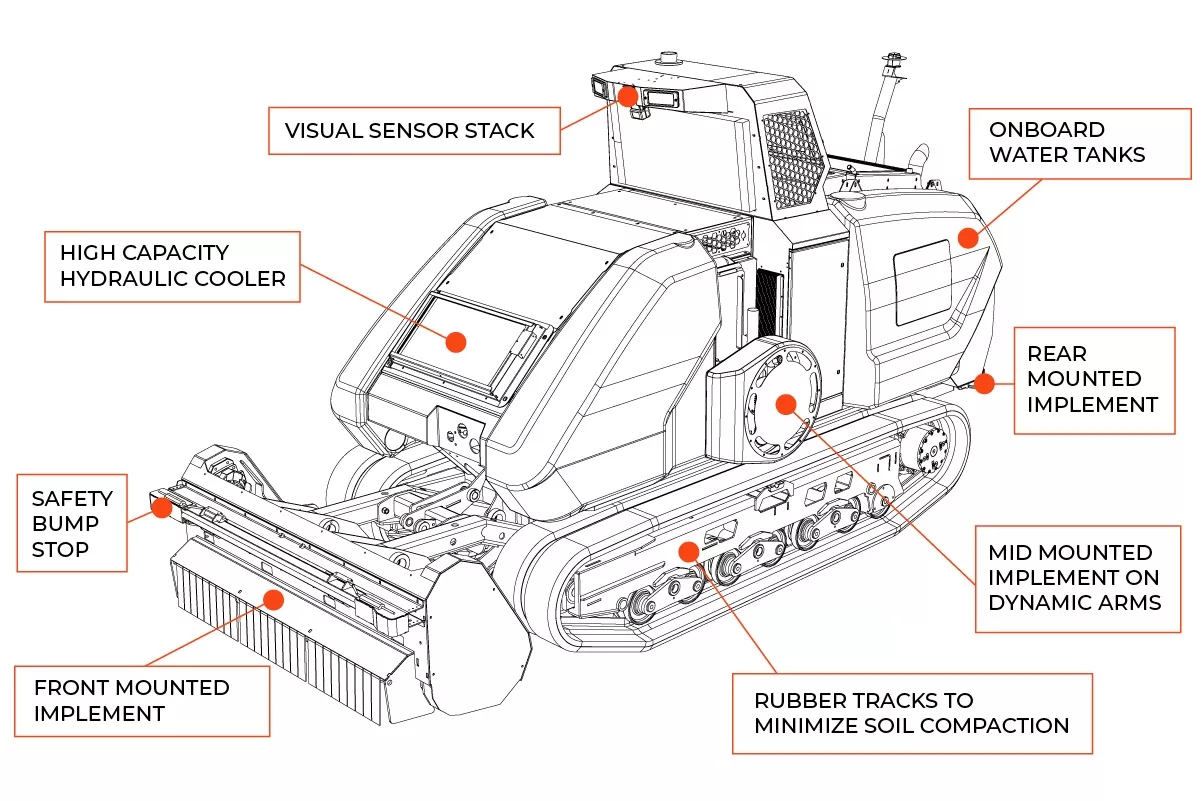

“We will look to find ways in the future of also participating during harvest, whether it be towing gondola or chaser bins to carry harvested grapes,” says Andrew Kersley, CEO of SmartMachine.

SmartMachine is in talks with U.S. manufacturers to produce the robots. This would be less expensive and risky than shipping units from New Zealand. The company has developed a partnership with agriculture equipment seller Pellenc America to market service and support for the robots in the U.S.

Before a robot can drive down a row, a worker has to map out the vineyard block in which the machine will complete tasks. This involves the use of a real-time kinematic positioning (RTK) app. RTK corrects for errors through a satellite navigation system.

“This is a fast and easy process. The first step is for a human worker to click every strainer post in the vineyard with the app Global Positioning System (GPS) Logger. Then the worker can create a mission, or task-focused trip, for the robot. For example, the robot can drive down every row or every other row to complete a task. The process of logging a block and then creating a mission takes approximately two hours for a 50-acre block,” says Kersley.

“We have added radar for heavier canopies and crops. An operator with a connected device like a tablet can run up to six machines at once, 24-7 if they wanted,” says Kersley.

He says workers supervising an Oxin need to remain connected to internet service.

“We use cellular networks where available or satellite networks like Starlink when cellular is not, for high-speed satellite internet access that ensures the operator is connected to machines,” says Kersley.

Farmworkers concerned

Farmworkers are concerned that these and other robots are not the subject of a two-way conversation between wine industry executives and workers, says Max Bell Alper, executive director of North Bay Jobs with Justice, a Santa Rosa-based community and labor coalition that includes farmworkers.

“We’re frustrated that wine grape growers, wineries and robotics manufacturers have not yet begun a conversation with vineyard workers about what these machines can do and how they will change the labor market. The topic is part of a bigger conversation about how the wine industry is treating the land and failing to consider the knowledge of immigrant and indigenous workers who have built the industry,” adds Alper.

As North Bay wineries and vineyards adopt such machines, farmworkers would prefer a “just transition” into careers in climate resilience, adds Alper, noting that many farmworkers have experience in wildfire-evacuation-route clearing, invasive-species removal, forest restoration after wildfires and creating defensible space around homes, among other resilience projects.

“We’d like to see trainings [conducted] in people’s preferred languages. In Sonoma County, one in three farmworkers speaks an indigenous language, including Mixteco, Trique, Zapoteco and Chatino,” says Alper.

“Technology is neither good nor bad. It’s all about context, who wields power in any given workplace,” says De Loera-Brust.

He says UFW wants to see workers at the table where discussions are being held.

“Recently, farmworkers in the Napa area have won lots of victories when standing up for themselves. For example, at several wineries in Napa and Sonoma counties, workers have been able to include protections against wildfires into their union contracts, including hazard pay of 150% when the Air Quality Index is over 150. And across California, recent legislation the UFW marched for has made it easier than ever for farmworkers to join the union, free from employer retaliation. In the past year alone, thousands of new farmworkers have unionized in California.” says De Loera-Brust.

“We’re frustrated that [wine-industry leaders] have not yet begun a conversation with vineyard workers about what these machines can do and how they will change the labor market.”— Max Bell Alper, executive director of North Bay Jobs with Justice

He sees the primary issue as robots like Oxin being seen as a cost-saving measure. That could undermine farmworkers’ bargaining power.

“I worry that we have a society where most farmworkers are treated as disposable. Many of these individuals are working well into their 70s because they never got a pension. Instead of having a conversation about retirement and health-care benefits, we’re talking about robots. We don’t want this to be the wine industry’s get-out-of-jail-free card to lower costs by avoiding giving the human workers who make this industry possible their due,” says De Loera-Brust.