A slick spiel and the click of a mouse are all it takes to lose one’s retirement savings, and it’s all too common a story.

When marking World Elder Abuse Day last June 15, the FBI reported that scammers had fleeced elders of $1.6 million from January through May of this year, and the number of complaints continues to grow. “We just keep hearing more reports of elder financial abuse,” says state Sen. Bill Dodd, representative for District 3, which includes Napa County and part of Sonoma. While historically family members or individuals with a close relationship to elders were most often responsible, he believes attempts to defraud elders are proliferating now because computers and mobile phones make elders vulnerable, and nefarious individuals often find it easy to confuse them, putting them in a position where they unwittingly make decisions that go against their own interests. Dodd explains that such people sound official and ask for a senior’s Social Security number or instruct them to wire money to a specific account for what seems to be a valid reason, and elders comply.

The FAST track

Fraud against elders is becoming more sophisticated, and finding and preventing it has become a priority for district attorney’s offices and social services agencies.

Mark Vanderscoff is Marin County public guardian and chairman of FAST—Financial Abuse Specialist Team. He works with Adult Protective Services (APS), which responds to allegations of elder abuse, 40% of which are financial. He finds that online fraud is prevalent, and romance scams are common. In many cases, a perpetrator establishes email communication, gets the victim to trust him or her and then asks for money. Almost a third of Marin’s population is older adults, and he observes that as people get older, they are often more isolated and get lonely, putting them at risk for scams. They also tend to be trusting, so if they’re using a computer and receive a message from a hacker telling them the computer has been compromised, they think they should respond immediately. Thus, they click on a link that takes them to a site where they are tricked into revealing personal information or sending money, usually with no chance of recovery.

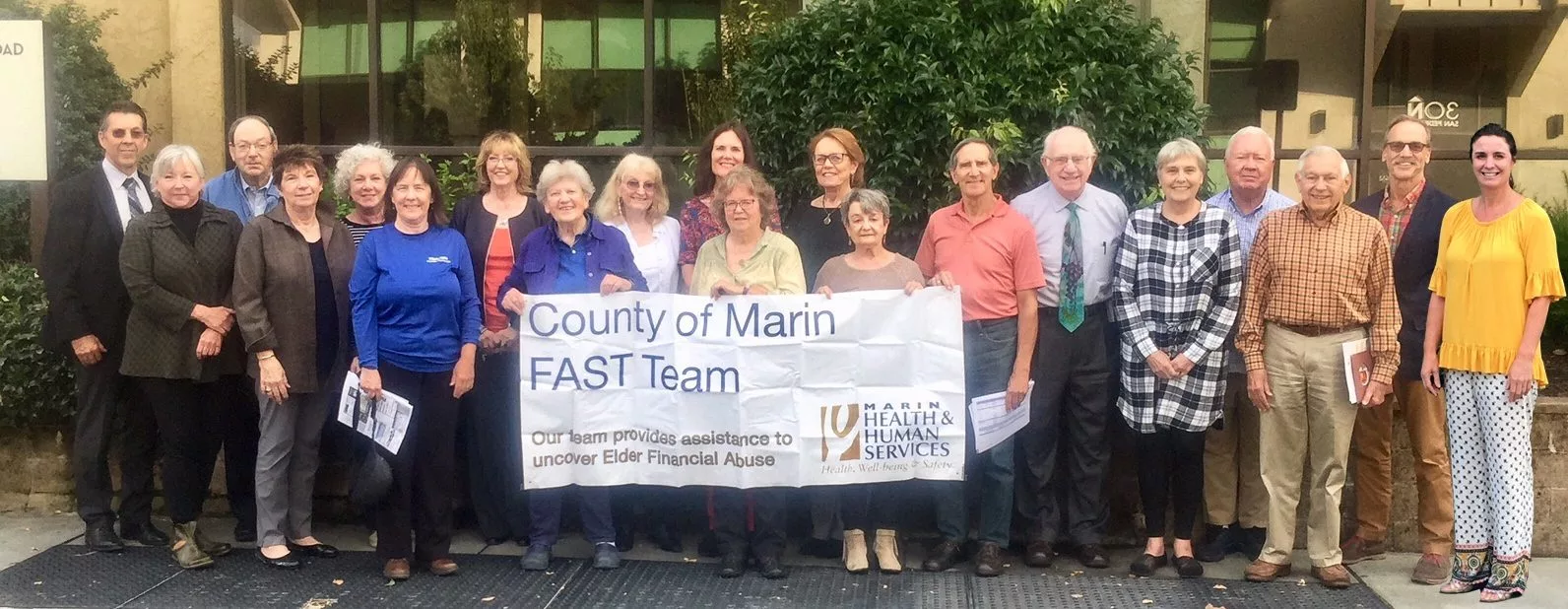

FAST is a mixture of public-sector employees and a group of 20 volunteers—mostly retired professionals who have worked in banking, law or real estate—and they have a two-fold mission. “One is to educate the public [as a way] to cut down on scams,” Vanderscoff says, and team members go into the community to give presentations at retirement homes, Rotary clubs and wherever people congregate. They explain current scams, tell people how to avoid them and give tips. The second part is doing forensic accounting and examining documents in cases referred to them by law enforcement or APS. Vanderscoff explains that it’s a valuable service, because the volunteers have the professional expertise to spot what’s suspicious, determine how much money is missing and find the accounts the funds went to. Team members then work with law enforcement to get subpoenas for those accounts, allowing them to create a full financial picture and confirm fraudulent activity.

The goal is to compile sufficient evidence for law enforcement or APS to refer a case to the Marin County District Attorney’s office for prosecution. It then falls under the purview of the Elder Abuse Program, a multidisciplinary team made up of prosecutors, law enforcement and public sector agencies dedicated to protecting elders from all forms of abuse. “We partner very closely with [Marin County District Attorney] Lori Frugoli and the DA’s Office, and that’s extremely important to the success of the team,” says Vanderscoff.

FAST was formed in 2005, and the current model has been in place since 2015. “Our volunteers are vetted by the county’s volunteer department,” says Vanderscoff, so they are fingerprinted, and background checks make sure they don’t have criminal records. They’re also trained in HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) compliance and sexual harassment. They have meetings every other month, and a member of the District Attorney’s office usually attends, along with law enforcement, Legal Aid [of Marin], APS and the ombudsman, who oversees nursing homes.

Elder financial abuse is an underreported crime, and “Unfortunately, we don’t get as many cases as we should,” he says, because older adults are often afraid that they’ll be seen as incompetent and fear repercussions. In addition, “They may trust their abuser,” he says, especially if the suspect is a family member. He recalls a Marin woman in her 90s who gave financial power of attorney to her nephew, a New York City resident who started spending her money on Broadway shows and trips to Africa. “It was pretty obvious,” he says, and APS found out and referred the case to law enforcement.

Seeking justice

In Sonoma County, the Elder Protection Unit in the District Attorney’s Office includes a prosecutor, investigator and victim advocate who are trained to work with elders and handle felony cases of financial abuse, as defined by California Penal Code Section 368. A case must involve $500 or more to be a felony, and cases that meet that threshold can be difficult to prove. A FAST team is invaluable in investigations, and District Attorney Carla Rodriguez explains that volunteers who are retired CPAs and lawyers help detectives wade through financials and help prosecutors explain how a theft or embezzlement occurred. “They help us present it to a jury, and they testify as expert witnesses,” she says, and sometimes they create pie charts to illustrate where the money went. In one case, a contractor who was installing solar panels for two clients strung out the work for several years and kept asking for more money. He bilked a combined $900,000 out of his elder victims, and FAST members found all his hidden accounts and showed that he wasn’t using the money for construction purposes. “That’s a violation of the law,” she says.

Among the challenges for prosecutors, they must prove that the accused knew the victim was 65 or older and unable to give consent. Rodriguez recalls a woman who was under duress behind closed doors, but when she went into her bank with her abuser, she appeared happy, so bank employees thought she was able to make her own financial decisions, and they couldn’t testify otherwise. In addition, “We have to make sure a victim can testify,” she says, explaining that cases can take a long time to investigate, and she’s had several victims pass away before their court dates. Therefore, when a case is filed, the prosecutor is allowed to do a conditional exam and videotape it to preserve testimony for future use. Her office also needs to be able to corroborate the victim’s version of events, perhaps with cell phone records and independent witnesses and have all the documentary evidence they need. In addition, they must make sure bank records still exist, especially in cases that take a long time to investigate. “We cannot file a case unless we can prove it without reasonable doubt so that 12 jurors could convict that person,” she says. “It’s really just working with an elder victim, being respectful of their status and making sure we don’t make it unduly stressful for that person.”

Getting restitution is difficult, because many people who embezzle money have spent it. “We always get an order,” says Rodriguez, and she explains that it’s easier in cases involving larger amounts, because her office can get injunctions and put liens on property. She worked on elder fraud cases for several years before becoming district attorney and says, “When I did elder abuse, I felt like I was being a bill collector.”

Not every case is a felony or even a crime, but remedies other than filing charges can help protect elders. Among them are restraining orders, powers of attorney and estate planning to safeguard a person’s money. Small claims actions are an option, and conservatorships are useful when someone has dementia and shouldn’t be making financial decisions. “We can’t give legal advice to victims. We only prosecute crimes,” Rodriguez says, but she will field calls from people who want to know what to do. She spoke to one woman who discovered that her husband had been signing over checks to a scammer for several months and given up $100,000. Rodriguez advised her to file a police report and told her, “It happens. Don’t be angry.”

An ounce of prevention

Learning about scams and ways to recognize them is one of the most effective ways for elders to prevent fraud. When Evan Lichtblau, 17, a senior at Tamalpais High School in Mill Valley, saw his grandfather entering information into his phone, something seemed amiss. Lichtblau intervened and discovered that his “abuelo” was the target of a scam. The older man had lost money to fraud previously, and “Knowing that he had fallen for this scam was frustrating,” Lichtblau recalls. He thought if he could explain to his grandfather how online scams work, he might be able to help others too. He started by serving an internship at the Marin County District Attorney’s Office and focused on finding ways to prevent online scams involving elders. Believing that talking to people directly is better than showing them a video, he created a presentation that he floated to staff in the district attorney’s office, and “They fully supported me,” he says. FAST gives general presentations, but his was specifically for teaching elders about online scams, and he approached Vanderscoff, who liked the idea too.

“The first I went to was at Drake’s Terrace in San Rafael,” Lichtblau says, and he’s also spoken at The Redwoods in Mill Valley and Aegis in Corte Madera. The response is largely positive, with smiles from engaged elders who raise their hands to ask questions. “From what I’ve seen they’ve been pretty open to listening to me,” he says, although a woman who’d been victimized broke down at one presentation. As part of his internship, he also produced a brochure for distribution to elders and wrote consumer tips on how to avoid online scams for the Marin Independent Journal.

He enlisted friends who wanted to help as well and started “Students Against Scammers,” a school club that operates independently. “We discuss scams, and then we’ll go over them, and they sign up for presentations,” he explains. He’s aware of up-and-coming ways to defraud elders and says, “When it comes to family and friends, I think the scariest of new scams is artificial intelligence.” He recounts the story of how a scammer impersonating his brother called his other grandfather to say he’d been arrested for DUI and needed money. The man didn’t fall into the trap. Instead, he called the young man’s parents to verify the story and discovered it was untrue. In that kind of situation, Lichtblau suggests confirming someone’s identity by asking a question only the person being impersonated would have the answer to. He believes talking to people who are technology-adept and getting second opinions is worthwhile too.

Putting on the brakes

Earlier this year, Dodd learned about a woman who had lost $900,000—her entire life savings—and stories like hers were the impetus for his sponsoring Senate Bill 278, Elder abuse: emergency financial contact program. The proposed legislation is designed to have banks and financial institutions play a greater role in preventing elder fraud by delaying a transaction at least three days if the account holder doesn’t know the recipient and can’t give a satisfactory explanation for the transfer of funds. The pause would allow time for a trusted third party to determine whether it’s legitimate. “Some banks were actually. aiding and abetting these scams by agreeing to wire funds,” Dodd says, because they sent the money requested without question.

At first, 13 financial and business organizations were opposed to the bill, because the original version included a $10,000 fine for every complaint against a financial institution and allowed consumer attorneys to take them to court. Dodd saw no reason to pile on fines, however, and after changes to address the issues and ensure that the proposed legislation wouldn’t unduly delay legitimate transactions, the bipartisan bill passed both houses at the end of August unopposed. Nevertheless, Gov. Gavin Newsom vetoed the bill at the end of September over fear it would interfere with lawful transactions, even though Dodd had worked with groups such as the California Bankers Association, which was unopposed to the bill after changes to allay its members’ concerns. The future of SB 278 is now uncertain. Legislators in the Senate and Assembly cannot serve more than 12 years, and Dodd is approaching that limit and isn’t running for reelection, so he will not be able to reintroduce the bill. “However, he is encouraging his colleagues to reintroduce it and to work with the governor’s office to address his concerns and get this important consumer protection measure across the finish line,” says Dodd’s press secretary Paul Payne.

Meanwhile, Dodd says that while some banks are already following good practices, not all are, and new measures would help. He adds that credit unions rarely have problems, because they’re local and focused on their members.

Redwood Credit Union collaborated with Dodd’s team to help craft the bill, and Mishel Kaufman, chief operating and risk officer, says they appreciated the opportunity. “The security of our members’ accounts and information is our top priority,” she says, explaining that RCU provides specialized training for employees to help them recognize suspicious situations and ask questions to determine if elder members might be at risk. RCU also offers community education sessions; five such sessions have been held recently, including one at a retirement community. Kaufman finds that some of the most common attempts to defraud elders involve lottery scams, IT support and cryptocurrency investments. Regardless of what kind of fraud it is, preventing it can be challenging. “Scammers spend a lot of time preparing their targets for any questions their financial institution might ask,” she says, and so victims might conceal the purpose of a transaction. And even though RCU educates members to safeguard private information, “Fraudsters are relentless and persuade target to give up their account credentials, passwords and even security codes,” Kaufman reports. While technology makes fraud easier for scammers, however, it also makes it easier for financial institutions to identify attempts while they’re taking place. “Our fraud detection systems are quick to catch unusual activity and notify members if a transaction needs validation,” she says.

It also pays for individuals to be diligent. Rodriguez gives presentations on fraud with Sonoma County Ombudsman Crista Nelson, and she tells elders and anyone related to them, “Don’t click that link in your email. Don’t ever give out any information over the phone. Go directly to the source. If it purports to be your bank, call your bank. If it purports to be Costco trying to get your membership renewed, hang up and call Costco.” Her biggest message is that victims shouldn’t be ashamed or embarrassed or feel any stigma. “The people who are committing these crimes are so sophisticated and so good at what they do, and the psychological coercion they use is so effective that anyone could be a victim of fraud,” she says. “The idea isn’t to punish people. It’s really to safeguard elders,” she adds, and every measure taken, whether it’s going public with an unfortunate story that someone else could learn from or taking time to check the legitimacy of a transaction, is one more step in the right direction.

Elder fraud red flags

The Marin County Financial Specialist Team suggests being on the lookout for the following signs of elder fraud:

- Isolating the elder by limiting contact with friends and other family members.

- The exercise of excessive control or sway over an elder.

- Sudden changes in the elder’s banking practice.

- Abrupt changes in a will or financial documents.

- Unexplained disappearance of valuable possessions.

- Substandard care being provided or bills going unpaid, despite adequate financial resources.

- Statements by the elder about suspected financial exploitation.

Deed fraud interrupted

When Marin County District Attorney Lori Frugoli and Assessor-Recorder-Clerk Shelly Scott became aware of an increase in fraud involving real estate in other areas, they created a deed program that takes simple but effective action to prevent it from happening on their turf. Now, “We notify property owners when a deed or transfer of titles occurs to make sure they are aware of the transaction,” says Frugoli. Owners receive a letter in the mail, and if they’re aware of the transfer and know it’s legitimate, they don’t have to do anything. If they don’t know about it, they’ll find contact information and instructions in the letter so they can report a fraudulent transfer. For more information, go to marincountyda.org/service/real-estate-fraud.—JW

Reporting elder fraud

The Sonoma County District Attorney’s Office recommends calling one of the following if you or an elder you know is a victim of fraud.

Local law enforcement

Adult Protective Services

Elder Protection Unit at the District Attorney’s Office

Department of Consumer Affairs

State Contractors Board

The FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center, IC3

AARP Fraud Watch Blog

Senior Medicare Patrol

US Postal inspectors

Federal Trade Commission