A ghostly, black and white image of a mountain lion appears on the computer screen. It moves gracefully through the grass; it’s eyes glow in the dark surroundings. A trail camera on Hood Mountain captured the image just days before. Seated at his desk, Dr. Quinton Martins’ face brightens. “What a magnificent animal,” he says. Over the years, Martins, director and principal investigator for the Living with Lions program at Audubon Canyon Ranch, has seen many big cats, yet his passion for these special creatures has never waned.

African beginnings

Martins hails from South Africa. He grew up with a menagerie of pets, from dogs and cats, to cockatiels and monkeys. “My father took me on fishing and camping trips. He instilled in me a love of nature,” Martins says. His work with animals began through guiding safaris and managing camps in Botswana where he tracked, observed and photographed wildlife. In South Africa’s Cederberg Mountains, he studied the elusive Cape mountain leopard and discovered many were being needlessly killed. He sold his car, his cameras, and everything he owned to undertake research, hoping to bring awareness to the leopard’s plight. Despite the hardships, he persisted. Eventually, a patron, Johan van der Westhuizen, heard of his work and provided much needed financial support. Martins and van der Westhuizen went on to found the Cape Leopard Trust, and Martins went on to complete his Ph.D. at the University of Bristol in the U.K. After 11 years as chief executive officer of the Trust, he yearned for an opportunity with a broader, more global scope. So when the Snow Leopard Conservancy based in Sonoma came calling, he jumped at the chance. “I saw California, with its intellectual and financial resources, as the prefect demographic for further research and commitment to finding more innovative ways to conserve our fragile environment,” Martins says. Under the umbrella of the Conservancy, Martins had already begun work with ACR and the Mountain Lion Conservation Program of the Department of Fish and Wildlife to document movement of individual mountain lions within the Sonoma Valley Wildlife Corridor. As the project gained momentum, Martins joined ACR full time.

Martins hails from South Africa. He grew up with a menagerie of pets, from dogs and cats, to cockatiels and monkeys. “My father took me on fishing and camping trips. He instilled in me a love of nature,” Martins says. His work with animals began through guiding safaris and managing camps in Botswana where he tracked, observed and photographed wildlife. In South Africa’s Cederberg Mountains, he studied the elusive Cape mountain leopard and discovered many were being needlessly killed. He sold his car, his cameras, and everything he owned to undertake research, hoping to bring awareness to the leopard’s plight. Despite the hardships, he persisted. Eventually, a patron, Johan van der Westhuizen, heard of his work and provided much needed financial support. Martins and van der Westhuizen went on to found the Cape Leopard Trust, and Martins went on to complete his Ph.D. at the University of Bristol in the U.K. After 11 years as chief executive officer of the Trust, he yearned for an opportunity with a broader, more global scope. So when the Snow Leopard Conservancy based in Sonoma came calling, he jumped at the chance. “I saw California, with its intellectual and financial resources, as the prefect demographic for further research and commitment to finding more innovative ways to conserve our fragile environment,” Martins says. Under the umbrella of the Conservancy, Martins had already begun work with ACR and the Mountain Lion Conservation Program of the Department of Fish and Wildlife to document movement of individual mountain lions within the Sonoma Valley Wildlife Corridor. As the project gained momentum, Martins joined ACR full time.

Audubon Canyon Ranch (ACR)

“It’s a lengthy process to get permission from California Department of Fish and Wildlife to trap and collar mountain lions,” says John Petersen, ACR’s executive director. “Quinton’s credentials helped with ultimate approval.” ACR is only one of five organizations in the state allowed to do this type work. “The cougar is an iconic species and brings much recognition and support to our lesser recognized yet equally important environmental efforts. The work Quinton’s doing is a perfect fit with ACR’s mission—land stewardship, nature education and conservation science. We’re fortunate to have him and his expertise as part of our team,” Peterson says.

ACR was founded in 1962 by a group of environmental advocates whose efforts saved Bolinas Lagoon and the nearby heronry from commercial development. Following that success, ACR has grown considerably. It manages four nature preserves covering 5,000 acres. The most recent addition, Modini Preserve outside Healdsburg, has 3,000 acres of prime wildlife and mountain lion habitat.

Martins and the Living with Lions project operate out of Glen Ellen’s ACR-managed Bouverie Preserve. British aristocrat David Bouverie acquired the 535-acre parcel in 1938. The land supports a diversity of plants and animals: 130 bird species, 350 types of flowering plants, and large mammals like the bobcat, gray fox, coyote and cougars. Bouverie lived there until his death in 1994. Concerned about encroaching development coming at both ends of the valley, he left the unspoiled acreage to ACR with the stipulation that it be used for the purpose of educating elementary school students. In addition to the fall and spring school hikes, the preserve also offers guided walks and twilight hikes for the public.

As a member of Sonoma Land Trust’s Corridor Technical Advisory Group and the Wildlife Observers Network-Bay Area, ACR identifies best management practices for the Bouverie property to ensure corridor values are protected. That includes assessment of wildlife, removing or modifying fencing, limits on nighttime lighting, and participation in two wildlife camera studies.

The Living with Lions program

Mountain lions are humanely captured, and those older than 11 months and weighing more than 50 pounds are equipped with GPS collars. Measurements and samples are taken to determine age and health, and to map the genetic makeup of the region and the state’s lion population. The collected data is made available to other NGO’s and to the public. In addition to Martins, the team includes ACR conservation scientists and educators, local veterinarians, geneticists, and volunteers who assist with fieldwork. Partners include California Department of Fish and Wildlife, California State Parks, the University of California, Berkeley, Sonoma Regional Parks, Sonoma Ag+ Open Space, and Sonoma Land Trust. Coupled with its research, Living with Lions also partners with landowners and managers to implement best practices to deter mountain lions from preying on pets and livestock. When conflicts arise, the public can call the Living with Lions team who will mobilize to create outcomes that benefit all involved.

The 2017 Nun’s Canyon wildfire

In October 2017, the Nun’s Canyon wildfire destroyed seven out of nine Bouverie buildings and 75 percent of the landscape. “When our office burned to the ground, we lost our computers, lab manuals, six new height sensor walk-through traps and GPS collars costing $3k each. Fortunately the mountain lions we were tracking were unharmed,” says Martins. Lions trapped after the fire showed no signs of distress, and the community responded in a big way to help. Most of the equipment lost has been replaced through donations.

Bouverie’s school program hosted approximately 3,000 elementary school students a year prior to the fire. With the loss of buildings, including the education hall, and trails being unsafe, school visits had to be cancelled. They started up again in spring 2018 after many trails had been rebuilt and hazards removed. Though still limited to one class a day, Bouverie hosted 1,756 students in the current school year. It’s expected the preserve will be back to two classes during the 2019 fall season.

Mountain lion characteristics

A recent study, co-authored by Martins and ACR, suggests around 47 percent of California is considered suitable habitat for mountain lions, also known as cougars, panthers or pumas. Their coat is uniformly tawny or beige in color. Their black-tipped tail, about one-third of their body length, provides balance for jumping and pursuing prey. “Mountain lions are very agile,” Martins says. “They can jump 15 feet from a sitting position, and on the run can leap 40 feet.” Males weigh from 120 to 160-plus pounds.

A recent study, co-authored by Martins and ACR, suggests around 47 percent of California is considered suitable habitat for mountain lions, also known as cougars, panthers or pumas. Their coat is uniformly tawny or beige in color. Their black-tipped tail, about one-third of their body length, provides balance for jumping and pursuing prey. “Mountain lions are very agile,” Martins says. “They can jump 15 feet from a sitting position, and on the run can leap 40 feet.” Males weigh from 120 to 160-plus pounds.

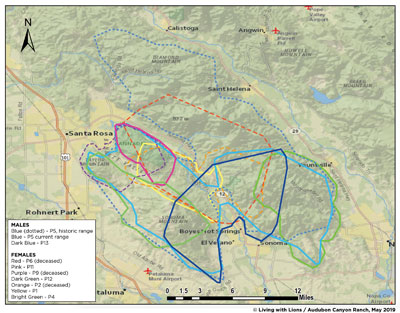

Females breed every two years and litters range from one to four cubs. “Social bonding is critical. If the mother dies within the first six months, her young have little chance of surviving,” says Martins. The cub’s spots provide camouflage, and then fade out after a year. At around 12 to 18 months, they leave their mother to seek their own territory. A male mountain lion’s range can extend from 100 to 200 square miles, and the female 30 to 70. Typically one to two lions occupy 50 square miles of habitat. Approximately 75 percent of their diet is deer, according to the ACR study. A cougar’s presence benefits the ecosystem—nutrients from deer carcasses provide rich soil supplements. And kills are an important source of food for other creatures: birds, mammals, reptiles and insects. “For an apex predator, mountain lions are quite timid. They tend to avoid people,” says Martins. Perhaps they learned from the past.

California history

Years ago, California teemed with wildlife. An estimated 10,000 grizzlies roamed the state. The last of those magnificent animals was killed in 1922, leaving the grizzly displayed on the state flag as a grim reminder. Lured by the offer of bounties—up to $60 for a female, $50 for a male—hunters killed 12,462 mountain lions from the period 1907 through to 1963 when bounties ended. Current estimates indicate there are probably 4,000 cougars in California. There are pockets, isolated by human encroachment, without access to genetic diversity that are at risk due to inbreeding. Ongoing studies hope to confirm the exact number in the state.

Years ago, California teemed with wildlife. An estimated 10,000 grizzlies roamed the state. The last of those magnificent animals was killed in 1922, leaving the grizzly displayed on the state flag as a grim reminder. Lured by the offer of bounties—up to $60 for a female, $50 for a male—hunters killed 12,462 mountain lions from the period 1907 through to 1963 when bounties ended. Current estimates indicate there are probably 4,000 cougars in California. There are pockets, isolated by human encroachment, without access to genetic diversity that are at risk due to inbreeding. Ongoing studies hope to confirm the exact number in the state.

In 1990, voters passed a measure banning the hunting of the species. Yet the law carved out a controversial provision. Landowners whose livestock is killed, or homeowners whose pet falls prey to a mountain lion, can obtain a depredation permit to kill the predator. “The law is antiquated,” Martins says. “Killing a healthy mountain lion doesn’t solve anything. If it’s a territorial male lion, the number of lions may actually increase as others move in to claim the now vacant territory. And killing the lion doesn’t take care of the underlying problem. Pet and livestock owners have a responsibility to keep their animals out of harms way. It’s hardly fair to the animals if they are left to fend for themselves. Good stewardship entails looking after those in our care.”

Most problems arise on small-scale farms with a few sheep or goats, or in neighborhoods where dogs or cats are left out at night. In 2017, eight Sonoma County residents sought depredation permits. P5, the resident male lion in the southern Mayacamas killed a rancher’s livestock and was targeted with a depredation permit. After meeting with Martins and learning about the importance of lions to the ecosystem, the rancher relented. P5’s life was saved.

Trapping

The first lion trapped and collared in the program was at Sonoma Land Trust’s Glen Oaks Ranch, adjacent to Bouverie. It was dubbed P-1, as in P for puma. Martins, together with Neil Martin of Santa Rosa-based Keysight Technologies, manufacturers of electronic measuring equipment and non-profit OneEightyStudio, built equipment with electronic height sensors that activate only when a lion passes thorough.

The first lion trapped and collared in the program was at Sonoma Land Trust’s Glen Oaks Ranch, adjacent to Bouverie. It was dubbed P-1, as in P for puma. Martins, together with Neil Martin of Santa Rosa-based Keysight Technologies, manufacturers of electronic measuring equipment and non-profit OneEightyStudio, built equipment with electronic height sensors that activate only when a lion passes thorough.

The walk-through trap is set along trails where mountain lion activity has been detected. “Animal safety is our primary concern. Our new high-tech traps eliminate the capture of non-target species and minimizes trap management,” Martins says. Setting of the traps is a high stress period for the Martins. “At night, my wife and I are on edge anticipating the loud clang of chimes that signals a lion has entered the trap.” Martins’ team is organized to respond and be on site within thirty minutes. “Trapping periods can last 4-6 weeks. After that we need a good nights rest and a nice bottle of wine.”

Wild Neighbors educational program

Liz Martins, Quinton’s wife and former Waldorf teacher, is Living with Lions’ education coordinator, a position similar to her role with Cape Leopard Trust. “In South Africa, I organized eco-camps for children to come and stay at the preserve. This gave them the opportunity to experience nature first hand,” says Liz. She also obtained grants to transport school groups from the townships to the Cederberg Mountain site. At ACR, she’s devised a 90-minute program for elementary school students, dubbed “Our Wild Neighbors.” Twelve volunteers have been trained as lion ambassadors. And they’ve been busy. Since inception in 2017, the program has been presented to 3,000 students in 130 classrooms. “Our Wild Neighbors” fits perfectly with Bouverie’s mission of educating school groups through docent-led nature hikes. A similar program for middle and high schools is in the works.

Liz Martins, Quinton’s wife and former Waldorf teacher, is Living with Lions’ education coordinator, a position similar to her role with Cape Leopard Trust. “In South Africa, I organized eco-camps for children to come and stay at the preserve. This gave them the opportunity to experience nature first hand,” says Liz. She also obtained grants to transport school groups from the townships to the Cederberg Mountain site. At ACR, she’s devised a 90-minute program for elementary school students, dubbed “Our Wild Neighbors.” Twelve volunteers have been trained as lion ambassadors. And they’ve been busy. Since inception in 2017, the program has been presented to 3,000 students in 130 classrooms. “Our Wild Neighbors” fits perfectly with Bouverie’s mission of educating school groups through docent-led nature hikes. A similar program for middle and high schools is in the works.

The Lion Ambassadors recently made a presentation in Talia Maas-Howard’s third grade class at Madrone Elementary School in Santa Rosa. With lights dimmed, volunteer Dave Traver, pretending to be a mother mountain lion, crouched low and moved among the desks, as if looking for prey to feed a litter of kittens. Mesmerized, the students tracked him with their eyes. Afterwards, pictures flashed on the wall. One showed a scene where mountain lions lived, the other where they had disappeared.

“What’s different?” Ambassador Julie Harts asks, while pointing to the two pictures. Hands shoot up.

“Where’s there’s no lions, there’s more deer, and no grass,” says one boy.

“And what do you notice about the creek?”

“The water’s not clear and the fish are gone,” says a girl with long dark hair.

“That’s right. Without grass or plants, the soil runs off into the creek. It’s called erosion.”

“And there’s not many birds or butterflies,” says another student.

“There’s nothing to attract them,” Harts explains. “So you can see, we need lions to keep the balance of our ecosystem. Animals and plants need each other.”

Melissa Ormandy is a lion ambassador and a Bovary docent. The 22 weeks Bovary docent training is intensive and incudes learning about plants, mammals, amphibians, birds, Native Americans, and working with children. “I was super excited to join Liz’ program and present in classrooms,” says Ormandy. She has a degree in animal science from California Polytechnic State University. “My studies in college allow me to see conservation from a unique perspective.”

In the MA drone Elementary school courtyard, Romandy and the other ambassadors organize a game. Students alternate roles of being a mountain lion, a deer and a tree. The deer wore a blindfold to emphasize the deer’s dependency on its sense of hearing at night. The student lion tries to creep up and tap the deer on the shoulder before being heard. The student tree acts as referee.

Back in the classroom, students were asked to complete mountain lion related short sentences like— I am…, I can.., I have. From the responses, the lion ambassadors composed a poem later sent to Madrone Elementary along with a lion photograph.

Santa Rosa appearance

As for youthful mountain lions, they tend to avoid public places, just like mature cats—though a youngster strolled onto Santa Rosa Plaza on an early morning in May. The lion hung out for several hours, snoozing in a planter box outside Macy’s. Its presence created quite a stir. Authorities blocked off nearby streets and employees couldn’t get to work. Concerned for the lion’s welfare, no one complained.

California Fish and Wildlife tranquilized the young lion and Martins took DNA samples. The male lion was tagged P18. “I’m thinking he recently left his mother and was striking out on its own. He probably came down nearby Santa Rosa Creek,” Martins explains. Fish and Wildlife relocated P18 to a wilderness area north of Santa Rosa.

Good Samaritans

On a stormy Friday night in January, a mountain lion jumped the fence at Willow Creek Ranch, a heavily wooded 247-acre property outside Jenner. Two llamas were killed. “We brought the goats into the barn at night. They didn’t mind,” says Maria Cardamone, owner along with husband Paul Matthews. “But the llamas preferred to stay outdoors. We adopted the retired Sierra pack animals five years ago. We never expected this to happen.” Paul and Maria could have gotten a depredation permit. Instead they called Martins. As long time supporters of ACR, they met him at an event and admired his work.

On a stormy Friday night in January, a mountain lion jumped the fence at Willow Creek Ranch, a heavily wooded 247-acre property outside Jenner. Two llamas were killed. “We brought the goats into the barn at night. They didn’t mind,” says Maria Cardamone, owner along with husband Paul Matthews. “But the llamas preferred to stay outdoors. We adopted the retired Sierra pack animals five years ago. We never expected this to happen.” Paul and Maria could have gotten a depredation permit. Instead they called Martins. As long time supporters of ACR, they met him at an event and admired his work.

Martins used the llama’s remains as bait. And at 4 a.m. on Sunday, the cougar was caught, tranquilized, fitted with a GPS tracking collar, and released. He’s known as P14, the fourteenth lion in the program— or more affectionately called Paul, for Paul Matthews. The capture and release in Jenner enabled Martins to extend his research into western Sonoma County. Since his release, P14 has been tracked to Bodega Bay, back up across the Russian River to Manchester and down to Fort Ross. For the past months he’s been hanging out in the area around Pt. Arena and Sea Ranch.

“What happened was an unfortunate incident. And yet the lion had just as much right to be here as us. Man and nature must learn to co-exist,” says Cardamone. “Our chickens used to be free range—but no longer. We’ve built a critter-proof run so they’re safe and bobcats won’t be tempted.” Maria and Paul bought the property in 2010 and have retired there. “It’s a special place,” says Cardamone. “It used to be a cattle ranch. There’s a lot of old barbed wire fencing still around. Our goal is to get rid of that so wildlife can freely pass through.”

Partnerships

Living with Lions formed a partnership with Justin Brashares, Ph.D., and the Brashares Lab of UC Berkeley. “This allows us to expand our research and study area to Mendocino County and the location of the UC Hopland Research and Extension Center, site of UC’s deer behavior and collaring project. It gives us access to innovative technology that provides higher resolution into interactions between predator and prey,” says Martins. “There’s potential for an exchange of data between a deer’s collar and that of the lion. Higher resolution will enable us to better understand what factors affect the mountain lion’s behavior like what attracts and what deters.”

Martins hopes to encourage more partnerships with the private sector similar to the one with Keysight, the Agilent Technologies spin off. “I’m hoping a security company might be interested in working with us and helping landowners by building and monitoring automated pens for livestock. A new form of security—livestock security,” says Martins. “I think there would be a lot of interest in that from a conservation perspective as well as at the commercial level.”

The future

Despite efforts to dismantle environmental regulations at the national level, Martins holds out hope. “I’m optimistic,” says Martins. “People who live here want the best for the land, and this special place where we live. With ACR’s support, we’ll continue our efforts to protect the apex mountain lion and in the process hope to preserve our ecosystems, and all the flora and fauna within.”

If you encounter a mountain lion:

Do not run.

Stay together in one group.

Never approach the mountain lion or offer it food.

Always leave the animal an escape route. Even if it means stepping aside so the mountain lion can move past you.

Face the mountain lion. Talk to it firmly while slowly backing away.

If the mountain lion does not leave, be more assertive. If it crouches and lays back its ears, bares teeth or twitches its tail, then shout and wave your arms and throw any object you have (water bottle, book, backpack) at the animal.

If the mountain lion attacks, fight back. Be aggressive and stay on your feet.

Pick up small children and place them on your shoulders.

Try to appear larger than the mountain lion. If you’re wearing a jacket, hold it open to increase your apparent size. If in a group, stand shoulder-to-shoulder to appear intimidating.

Give a mountain lion or mountain lion kittens plenty of room and leave the area as soon as possible. Mountain lion kittens can look similar to domestic cats.

Mountain lion attacks are extremely rare. They are very good at avoiding people and generally behave indifferent toward us.

Source: 2018 WildFutures