Born in 1876, Jan. 12, marks the 145th anniversary of Jack London’s birth—an event that almost didn’t happen. His mother, Flora Wellman, pregnant and unwed, twice attempted suicide. The father, William Chaney, denied the baby was his and left town. Unable to provide nourishment, Wellman gave the baby to Jenny Prentiss, an ex-slave from Tennessee, to wet nurse. The child lived with Prentiss and her family in Oakland for three years, and off and on between homes for several years thereafter. An active infant, he reminded Prentiss of a jack-in-the-box. She called him “Jackie.” According to Jack, she was like a second mother, the only one who showed him love and affection. Their bond lasted a lifetime. Copies of his books he gave her are inscribed from “your son.”

Eight months following the baby’s birth, Wellman married John London, a Civil War veteran, carpenter and widower with two young daughters. He provided Jack with a new surname. Until age 20, Jack believed John London was his biological father. He tracked down Chaney and they exchanged letters. Chaney continued to deny paternity.

From this fragile beginning, Jack would go on to become a famous writer, an adventurer and a sustainable farmer. The pursuits often overlapped, one influencing the other. London’s successes came amidst hardship and challenges that would have deterred any ordinary man.

Finding his way

The London family struggled and Jack did his part to help. At age 10, he delivered newspapers. At age 14, he worked 16-hour shifts in a pickle cannery earning 10 cents an hour. The Oakland Public Library became his refuge, where he spent hours devouring books that took him to faraway lands.

He roamed the Oakland waterfront. A boy among men, he learned to box, drink and spin yarns. He developed a fondness for sailing, and not always for leisure. The railroad controlled oyster beds in San Francisco Bay and oysters were sold at inflated prices. A band of oyster pirates formed to thwart the monopoly. With $300 borrowed from Prentiss, London purchased the sloop Razzle Dazzle and became one of them. Pirating was dangerous business. Under cover of darkness, they raided beds protected by armed guards. They sold their take at prices most people could afford. Ironically, London’s skills as a pirate caught the attention of the head of the state fish patrol who hired him at no salary, instead offering a share of fines collected. When the mainsail of the Razzle Dazzle burned, London moved on.

Curiosity and the thrill that comes with personal accomplishment drove much of London’s early life. At age 17, he signed on to the crew of the Sophie Sutherland, a 157-ton, three-mast schooner headed to hunt seals off the coast of Japan. The voyage took about seven months. Along the way, the schooner encountered a violent typhoon. “Possibly the proudest moment of my life occurred when I was seventeen,” London wrote in the preface to The Cruise of the Snark. “I was called from my bunk at seven in the morning to take the wheel. The sailing master watched me… afraid of my youth, feared I lacked the strength and the nerve. I stood there alone….I saw it coming, and, half-drowned, with tons of water crushing me, I checked the schooner’s rush to broach…At the end of an hour, sweating and played out, I was relieved. But I had done it! With my own hands I had done my trick at the wheel and guided a hundred tons of wood and iron through a few million tons of wind and waves.” That event led to London’s first literary endeavor. He submitted an essay “Story of a Typhoon off the Coast of Japan” to a contest sponsored by a San Francisco newspaper, and won. The win would serve as a writing placeholder. Years, and more adventures would pass before he took up his pen to write about them.

In 1894, industrial unrest spread across the country. Workers demanded fair wages and better working conditions. London adopted their demands as the rallying cry for the brand of socialism he espoused throughout his life. He joined a detachment of 2,000 men traveling in boxcars headed to Washington, D.C. to protest. He’d spent his youth toiling in factories and sympathized with their cause. With the band of protesters, he hoboed his way across the country and experienced the plight of the unemployed and farm workers.

After reaching D.C., he followed the rail line home via Niagara Falls. He asked a policeman for directions, was arrested for vagrancy and sentenced to 30 days in jail. Dispirited by the experience, London vowed to do all he could to help the common man, but realized that before he could do that he needed to further his education. When he returned to Oakland, he studied and passed the entry exam to the University of California, Berkeley. After one semester he dropped out, finding it “not alive enough.” And he needed to help his family.

In July of 1897, the cry “gold in the Klondike” drew men from all over the world. Jack joined them. Few got rich, thousands perished in the harsh winters. Though Jack didn’t discover gold, he returned home a year later with experiences that would later serve as material for some of his best writing.

The Writer

In 1898, vowing to never again be a “work beast,” London took up writing as a profession. He still labored long hours every day, writing. With little money for sustenance, he fought off bouts of illness. Years later his novel, Martin Eden, a story about a struggling writer, drew heavily on that experience. The Overland Monthly magazine published his first short story, “To the Man on the Trail.” A Daughter of the Snows, set in the Yukon with a female protagonist, was his first published novel. Call of the Wild brought him fame. The story stars Buck, a St. Bernard mix who’s taken from a family in Santa Clara Valley, shipped to Alaska and tossed into the rough and tumble world of the Klondike. The book launched London’s career. He became a celebrity, and the highest paid author in the world.

Return to Adventure

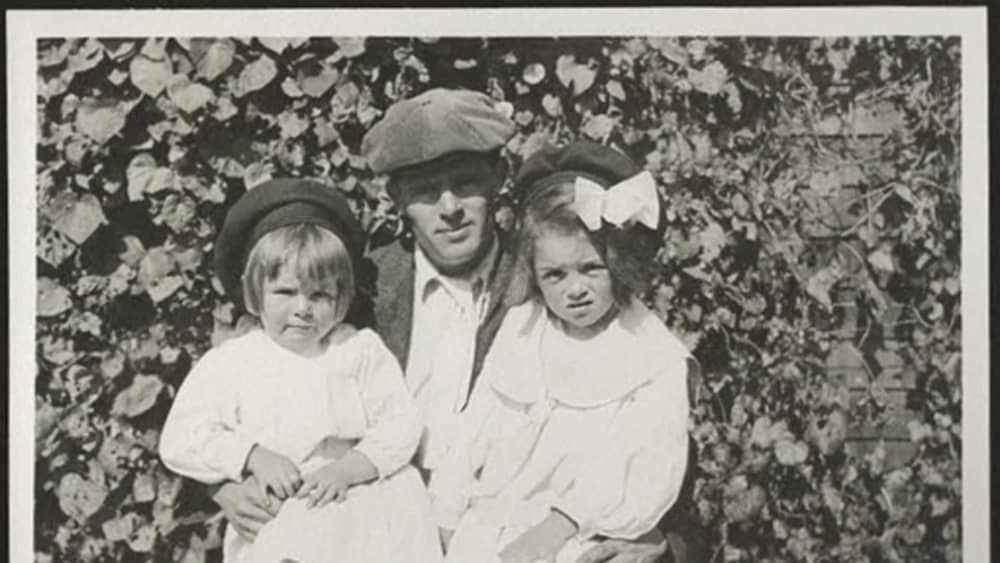

In 1900, Jack married Bess Maddern in a union not destined to last. They were polar opposites, she quiet and reserved, he boisterous, social and one who loved life. After three years and two daughters, they separated. The divorce that followed was not amicable. In 1905, with the divorce finalized, Jack married Charmian Kittredge, Maddern’s best friend. Charmian, like Jack, was daring, spirited and an adventurer.

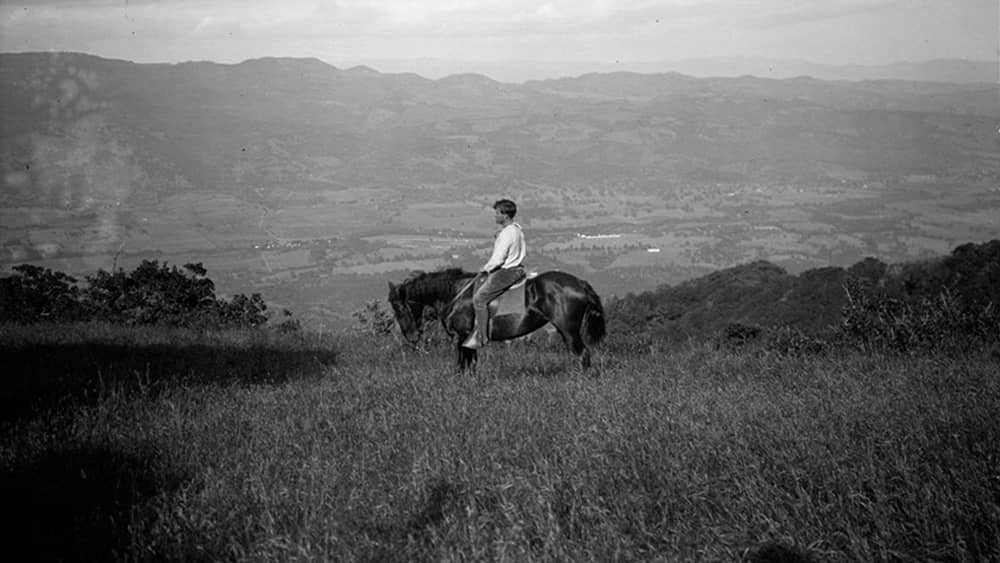

London purchased several parcels in Glen Ellen that eventually totaled 1,400 acres. The land appealed to his sense of beauty and love of nature. He named it “Beauty Ranch.” The Londons pondered a decision— build a dream house, or sail around the world. Excited at the prospect of travel and adventure, they put the house on hold.

If London had a flaw, it was his trust in people who let him down. The Snark, a 45-foot ketch, was built in San Francisco to Jack’s specifications and design. Charmian’s uncle, Roscoe Eames, oversaw construction, though he lacked experience. And he became voyage navigator. A San Francisco Bay yachtsman, he’d never sailed on the open seas. In April 1907, the Snark, and crew of five left the Oakland Estuary, sailed out of San Francisco Bay and set a course for Hawaii. Almost immediately, things fell apart. The cook and cabin boy got seasick. Compartments meant to be water tight, leaked. Iron fittings broke. The boat wallowed in the troughs. And they got lost. Jack stepped in, and learned navigation on the spot. Twenty-seven days later, they limped into Honolulu where they remained while the Snark underwent repairs in Hilo. Eames returned to California.

Five months later, with repairs finished, they headed off on a voyage that took them through the pristine, primitive islands of the South Pacific— Marquesas, Tahiti, Samoa, Fiji and the New Hebrides. In the Solomon Islands, the crew became ill with deadly yaws, an infectious bacterial tropical disease. Jack was the most affected. Treatment involved rubbing mercury-laced ointment into open sores. London did that for four months. With London ill, they left the Snark in Guadalcanal and took a steamer to Sydney, Australia. There he remained in a hospital for several weeks. After a year and a half, the voyage of the Snark ended. The Londons booked space on a cargo ship, and headed home.

Tragedy begets tragedy

Charmian became pregnant, the culmination of the couple’s desire to have a family. In a difficult delivery, she gave birth to a beautiful baby girl they named Joy. The baby lived for just 38 hours.

In his grief, London turned his attention to Wolf House, a 15,000-square-foot mansion to be constructed of lava rock and redwood timber, a house with 26 rooms and nine fireplaces, a house meant to stand “a thousand years,” as London liked to say. In 1913, the construction cost approximately $75,000, what would be priced at nearly $2 million today, according to the U.S. Inflation Calculator. A month prior to the Londons moving in, Wolf House caught fire. When it was over, smoldering rock and blackened chimneys were all that remained. Though some suspected arson, in 1995 forensic experts determined the cause was spontaneous combustion. Workers left linseed oil soaked rags in the wood paneled dining room. On that hot night, the rags ignited. Largely uninsured, the Londons were laden with debt, and without the funds Jack needed for his farm. Undaunted, he got advances from his publishers, a practice he would come to rely on.

That same year, London experienced severe pain and was rushed from Sonoma to Merritt Hospital in Oakland where he was operated on for appendicitis. He survived surgery, but the doctor found something more serious. His kidneys were failing. To prolong his life, the doctor advised London to take it easy, and rest. Its doubtful London mentioned yaws and the mercury-based treatment. No one had determined the adverse effects of mercury on the body. And it’s doubtful the doctor warned London about the risk of his heavy smoking. The adverse health effects of cigarettes had yet to be discovered. London refused to alter his lifestyle. And he didn’t tell Charmian about his potentially terminal illness. Instead, he turned his energies to Beauty Ranch.

Sustainable farming

Early pioneers farmed the land in Sonoma County until it was depleted, then moved on. London was incensed by their disregard. An avid reader, he was taken by the writings of John Muir and other conservationists. They advocated for the preservation of California’s natural resources and the reversal of the adverse effects of 19th century farming, logging and viticulture practices. He restored his Beauty Ranch and pursued sustainable farming, though the term was unknown at the time. “I am rebuilding worn-out hillside lands that were worked out and destroyed by our wasteful California pioneer farmers,” London said. “I am not using commercial fertilizers. I believe the soil is our one destructible asset, and by green manures, nitrogen-gathering cover crops, animal manure, crop rotation, proper tillage and draining, I am getting results the Chinese have demonstrated for years.”

A man of big ideas, London didn’t shy from experimenting. Guided by readings and university department of agriculture scientific publications, he planted 84,000 eucalyptus trees native to Australia on the property. Promoted as a fast growing hardwood, London planned to sell them for use in construction and furniture making. The eucalyptus species London and other Californians purchased, however, turned out to be an inferior softwood subject to twisting, splitting and was highly flammable. There is a eucalyptus hardwood, but like other hardwoods, it takes years to mature. He learned from his farming experiments, and persevered.

London referred to the farm animals brought to the area by early pioneers as “scrub.” Determined to bring in better breeds, London read agricultural journals and scoured the country for the best purebreds.

He eventually acquired prized Jersey Duroc hogs. When a few died of cholera, London suspected the local butcher was responsible for tracking in the deadly germ. He installed a gated entry with a carbolic acid footbath through which visitors would have to pass, and he designed and built a sanitary, state-of the art piggery, the design perhaps reminiscent of the Amish round barns he had seen years earlier when he hoboed his way across the U.S.

A high, round stone tower with a concrete conical roof centered a shaded courtyard. A gravel path and outer ring of seventeen pig apartments, each with a patio, an enclosed shelter and a fenced off exercise area, encircled the center structure. The upper level of the tower stored feed. When a metal flume opened, feed dropped into a basin below where the slop was mixed. Each apartment could house a 700-pound sow and litters of 10 to 14 piglets. The turn of a single tap provided each pen with water. With London’s unique layout only one worker was needed to care for more than 200 pigs. “….I am building a piggery that will be the delight of all pig-men in the U.S. It will be large and efficient and cheap….” London said. Large and efficient it was. At a cost of $3,000, it wasn’t cheap. And many scoffed. When it was finished, Jack invited reporters to see what he had done. One of them dubbed it the “Pig Palace” after San Francisco’s famous, elegant Palace Hotel.

London saw his bulls lazing in the shade while cows birthed calves and produced milk. He decided they needed exercise. He designed and built a bull exerciser, a rotating contraption set atop a circular stone base. Bulls, hitched up to a pole, walked and walked, in a wide circle.

London devised a liquid manure system with a pipe that ran from the cow barn down to a concrete holding tank. Horses pulled a small wagon tanker with sprayers that dispersed liquid fertilizer onto the crops. The system was revolutionary for the time.

London’s ranch menagerie grew to include 55 Angora goats, 600 white Leghorn chickens, the Duroc Jersey hogs, a flock of pheasants, a herd of Shorthorn cattle, Jersey cows and 6 thoroughbred Shire horses. With 50 workers, the ranch hummed with activity.

Earle Labor, London biographer, wrote, “…London was regarded by the agricultural experts of his time as “one of California’s leading farmers’ and that his model ranch was considered ‘one of the best’ in the country.

The final years

Three years after his fatal kidney diagnosis, Eliza Shepherd, Jack’s half-sister and ranch manager roused Charmian from her slumber. “I think you’d better come…,” she said. Jack lay doubled over on his side on his sleeping porch. Unconscious, he breathed heavily. Unaware of his terminal illness, the women suspected food poisoning. London never regained consciousness. On November 22, 1916, Jack London died of kidney failure, caused by the mercury-based yaws treatment.

At the young age of 40, London accomplished more than most men. He left behind a treasure trove of literature—50 books, more than 200 short stories, some plays, poetry and numerous essays. His books are widely read and several have been made into movies. The fifth film production of Call of the Wild starred Harrison Ford. Buck comes to life through computer-generated animation.

The recent movie, Martin Eden, based on a London novel, was produced in Italy and set in Naples. There’s an all-Italian cast. Dialogue is in Italian with English subtitles. As stated in an October, 2020 New York Times review, “The entirety of the 20th century—its promises, illusions and traumas—sweeps through the audacious and thrilling Martin Eden…The true miracle of this film is how Italian director Pietro Marcello translates both London’s scabrous tone and his lush, character-revealing prose into pure cinema.”

London’s legacy

In January, 145 years after his birth, Jack London’s legacy lives on in Glen Ellen, and guests continue to visit the homes and grounds of Jack London State Historic Park. They come to pay homage and explore the vestiges of London’s beloved, aptly named, Beauty Ranch. Many are from Russia. Steinbeck and London were the only American writers whose works were translated into Russian and allowed to be taught in public schools.

A recent Russian visitor, 87-year-old Alla from a village outside Moscow, made her way up the path as she returned from London’s gravesite. “I love Jack London,” she said. ”By the time I was 12, I’d read 10 of his books. My favorite is Martin Eden.” She spoke in Russian. Her son, Ivan, of Elk Grove, Calif., translated her words, “Jack London is famous in my country. Most of my life I dreamed of coming here and visiting his grave.”

Attributed to London, this quote embodies his bold philosophy of life: “I would rather be ashes than dust! I would rather that my spark should burn out in a brilliant blaze than it should be stifled by dry-rot. I would rather be a superb meteor, every atom of me in magnificent glow, than a sleepy and permanent planet. The function of man is to live, not to exist. I shall not waste my days trying to prolong them. I shall use my time.”