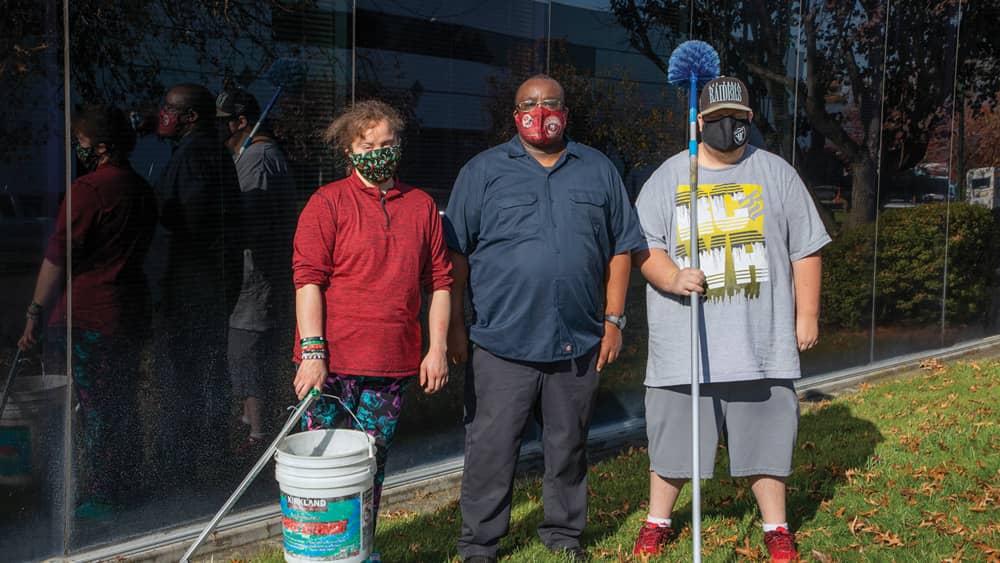

Calvin Calloway has been an employee with United Cerebral Palsy of the North Bay for 20 years “give or take,” he says. “I used to work on the bus shelter crew in Marin County, then I worked at Friedman’s Home Improvement in Petaluma for three years. Now I’m the job coach for the mobile crew in Petaluma, cleaning offices and other buildings.”

“Calvin went from participating in the crews to being the team lead/coach,” says Margaret Farman, CEO of UCPNB.

Calloway, 44, is a uniquely gifted individual, who was hired by UCPNB as a job coach to the crews that he was once a member of, while engaging in employment training. He is among the 300 uniquely-abled persons working in various capacities under the UCPNB umbrella, which overall has 500 employees in Sonoma, Napa and Solano counties.

“Most of our employees were born with their disabilities,” says Farman. “These can include cerebral palsy, autism, Down Syndrome, epilepsy and developmental or intellectual delay. The largest percentage of our employees falls into that category, and 13% have cerebral palsy. Generally, we have a mix of all forms of diagnosed developmental disabilities.”

Farman says historically the staff in the healthcare industry referred to individuals with disabilities as “high or low functioning,” but the organization does not use those labels. “We try not to use that language; it is a dehumanizing label. UCPNB’s mission is: “Work, Play and Learn Without Limits” and believes every individual can achieve their potential.

Michael Lisenko, director of business operations for UCPNB, also prefers to call their disabled clients “uniquely-abled.”

The organization’s aim is to advance the uniquely abled to a higher level of productivity and increase their training. “Our goal is to find them the kinds of jobs that match their individual career goals, talents and gifts,” adds Farman. “Many of us in the industry refer to this as ‘job carving,’ to carve out a job that’s unique to the individual.” Persons with disabilities, she adds, don’t want to be looked at just through the lens of their challenges, but through the lens of their talents, hopes and dreams. “Each of them is unique and has his or her own capacities and challenges,” she says. “Like so many things in life, their path is determined by their individuality.”

Taking pride in their work

The uniquely-abled employees of UCPNB with jobs generally fall into two categories: they are in a group-supported employment situation or an individual employment role. Calloway, for instance, is a participant turned staff member who currently coaches three other participants and supervises the Mobile Janitorial Work Crew in Petaluma, according to Tony Montoya, the director of supported employment for the organization.

Frequently, an employee with unique abilities begins training with a group of their peers and then explores community employment as an individual. One participant, says Farman, was recently hired as a job coach who is training other uniquely-abled employees in the organization. “It may take the individuals a bit longer in their career trajectory to meet their goals, but they are very dedicated and can even work out to be a better business fit than say a typical non-disabled employee. The individuals we work with take a great deal of pride in their work and have developed job habits, such as being punctual well-groomed, and exceptionally loyal. That’s not always true for typical non-disabled employees.”

In UCPNB’s social enterprise programs, participant referrals typically come from the North Bay Regional Center, one of 21 centers statewide for persons with developmental disabilities monitored by the California Department of Developmental Services (DDS). North Bay Regional Center works with UCPNB to determine person-centered goals and a plan, as well as reimbursing UCPNB for their support of that individual. “Another way we get referrals is through the California Department of Rehabilitation (DOR),” she adds. “In that case, an individual with a disability might seek the DOR’s help because they may have just become disabled, or they need to change jobs. In these cases, we receive referrals from the DOR for job assessment and training. Usually, those persons become employed directly by a community employer, and we provide the job coaching.”

In our social enterprise businesses, employees are given the opportunity to work one to four hours per day, depending on their desire and nature of their disability, says Lisenko. “We pay all of our employees with disabilities a minimum of minimum wage. There are many programs that pay employees with disabilities sub-minimum wage. Fifteen years ago, when we started our social enterprise programs, disabled workers were paid far less than nondisabled workers for identical work tasks due to the predominant sub-minimum wage pay. We just didn’t feel right about that.”

In many cases, Farman says, UCPNB offers a continuum of service from what’s considered most restrictive to least restrictive in terms of jobs and hours worked. “Many of our employees start working with a counselor in a business setting that supports them with job skills acquisition. From that point, they can graduate into group-supported employment, when a job coach is always with them. The distinction between social enterprise employees and group employment employees is that the social enterprise employees can work up to four hours per day, depending on their capacity and interest, and in group-supported employment, we want participants who can work a full 6- to 8-hour shift each day with the ability to stay focused.”

The UCPNB staff is trained to provide support around job skills and some employment behavioral support, as well, she says. “We teach our participants how to communicate professionally, how to not lose their cool over something in the job setting, and to take in information and process it by explaining it a couple of times.

“On average, people want a different job challenge every five to seven years, and someone uniquely-abled might want to tackle something new,” Farman adds.

Once a company hires a UCPNB work crew or someone with a unique ability, they discover that these individuals are often highly inspirational, says Farman, which can build a great deal of positive morale for the rest of the employees. “Your workplace will become a much happier and productive place.”

Praise for UCPNB crews

Marcos Norona, manager of Friedman’s Home Improvement store in Petaluma, says the UCPNB crew working there is always reliable, responsible and professional. “They perform many invaluable cleaning and maintenance duties at our store, including sweeping, vacuuming, removing trash, retrieving shopping carts and wiping down work stations.”

The crew, he says, is comprised of four people who work at the store five days a week, Monday through Friday. (According to Farman, UCPNB crews have worked at the Petaluma store since its opening in 2014; crews have worked at Friedman’s Home Improvement’s Sonoma store for 10 years.)

“When we recently conducted interviews for open positions at the Petaluma store, several candidates commented on the cleanliness of the store, inquiring how we are always able to keep it looking so nice,” says Norona. “This is a direct testament to our UCP work crew. Their dedication in completing their tasks to the highest levels leaves a lasting impression on our community and our team members.”

Also in Petaluma, a UCPNB landscaping crew keeps the grounds looking sharp at the Petaluma Valley Medical Center Group building on Lynch Creek Way. “I started my job 23 years ago, and UCP crews were already working at that site,” says Corinne Heald, office manager for Rohnert Park-based Eugene Burger Management Corporation, which manages the building. “The crew comes twice a week to mow the lawn, pick up trash and trim shrubbery. They do a great job keeping it looking nice.”

Vanessa Garrett, director of public works for the City of Rohnert Park, says the UCPNB crews working there generally handle tasks in city parks from one to three days per week. “We have 14 parks and facilities where UCP crews handle various tasks, and some are fairly large parks. In summer the crew works two or three days a week, doing grounds keeping and picking up trash, and in winter it’s about once a week. We have an agreement in place with them that is self-directed, so they can work whatever days they want. We recently renewed the contract for their help for three more years. It works great for us, and it’s obviously been successful. They have been a good addition to the park’s beautification of the city.”

Packaging and shredding

In Napa, approximately 96 employees with disabilities work at WineBev, which provides wine packaging and gift assembly services for the wine industry. “A good portion of our project activity is known in the wine industry as a ‘kitting’ service. Kitting essentially is defined as putting together various sized wine shipping packages and getting wine gift boxes ready for filling with bottles of wine,” Lisenko explains. “WineBev was our first social enterprise program and is located in the Napa Valley.”

Gone for Good in Fairfield, he says, is another facility that employs 88 UCPNB participants who handle paper shredding for the Internal Revenue Service, among others. “The IRS contract is through Source America, a branch of the government that ensures that uniquely-abled persons are provided access to perform government-related work. Gone for Good is a recycling center and is also becoming a thrift store processing center for our Flipside Thrift Stores.” Currently, the organization has two stores—one in Rohnert Park and the other in Santa Cruz.

Because of the sensitive nature of shredding for the IRS, the center has been certified by the National Association for Information Destruction (NAID)—not an easy certification to acquire, says Lisenko. “NAID comes in and examines that your processes are secure. There are cameras everywhere, and all employees working there must undergo a background check by the Department of Justice and the Federal Bureau of Investigation. We also provide mobile shredding pickup services, but instead of shredding onsite at the business location, we take away locked bins and shred at Gone for Good, where the sorting of shredded material is done by our uniquely-abled employees”

A NAID certification, he adds, is a great tool for generating additional shredding contract business.

Even uniquely-abled senior citizens want to remain active and engaged, says Lisenko. For that reason, UCPNB runs a senior center in Rohnert Park specifically designed to provide day activity services for seniors with disabilities. Participants in UCPNB’s Senior Adult Program participate in art projects and recreational activities both onsite and in the community.

Lisenko says during the pandemic, the organization’s recycling and wine industry services (WineBev and Gone for Good) were all considered essential businesses. Because of health and safety reasons, the State of California’s Department of Developmental Services made it mandatory that no participant employees could be served beginning in the middle of March 2020. WineBev and Gone For Good were able to retain their business contracts because of the willingness of their amazing team of direct service professionals to work throughout the pandemic. “Like all businesses, we were tasked with ensuring a safe and healthy environment for our employees,” he says. “We strictly adhere to all the local Public Health and Safety guidelines, while staying open to meet the needs of our customers. In doing so, we were able to retain and even grow our business contracts to ensure that we would have plenty of work available for our participant employees when they were permitted to, once again, attend our social enterprises.

“Our participant employees began coming back to work a few months ago, but on a limited basis due to safe distancing requirements,” Lisenko adds. “The hope is that the pandemic ends as soon, and when it’s safe, all employees return to the work they enjoy so much.”

As press time, UCPNB was still somewhat constrained by safety protocols. “Like all businesses at this time, we have to be vigilant and provide our services safely, while continuing to pay close attention to all state and county public health requirements.”

Yet, most of the disabled workers were passionate about coming back when it was deemed safe for them to do so, he adds. “We had to figure out a way to bring people back fairly because we were only able to call back 20% of the workforce. It required a lottery process, where we were drawing names out of hats.”

The importance of recreation

It’s not all work and no play for the uniquely abled, however.

“One of the great things we do is support our participants in creating a balance between work and recreation in their lives by helping them understand that recreation is important and healthy,” says Jennifer Whalen, director of community programs for UCPNB.

Bike camps are usually conducted in summer on the Sonoma State University campus, where kids and adults with disabilities learn how to ride a bike for the first time. “Last June, we taught 25 kids and young adults, using adaptive bikes. Our participants with autism usually need some assistance to help them process the safety aspects of biking, which can be more of a challenge for them than having a physical fear of a bike.”

Whalen also conducts adult activities at Camp Arroyo in Livermore, serving adults with disabilities, usually twice a year in November and June. The pre-pandemic camps included 65 to 70 participants; the latest camp numbered around 40. “Camp Arroyo is a three-day social retreat where we run recreational programs that are like a vacation for them. It’s a time for participants to get away from their group homes and families and enjoy outdoor fun.”

Another camp held in summer for school-age children with physical and intellectual disabilities, called Camp Kaos, takes place at Howarth Park in Santa Rosa. “We also refer to it as a week without limits,’” adds Whalen.

The pandemic put a hold on these recreational opportunities in 2020 but most made a comeback in 2021, generally with fewer participants to maintain safe distancing.

Helping his team grow

Calloway, the 20-year UCPNB employee working in Petaluma, says it’s a great organization to be associated with. “They care about the disabled people and do the best they can to train them to one day work in the community. They are very good at helping them find jobs, and won’t set up someone in a position where they won’t do well. They go that extra mile to make sure they will succeed by matching their skills to the right jobs.”

Meanwhile, he adds, “I’m trying to help my team grow, to make them better workers. So I’m not going anywhere.”

Work & Play

With 500 employees in Sonoma, Napa and Solano counties, Petaluma-based United Cerebral Palsy of the North Bay operates numerous businesses in these counties that provide jobs and job training for approximately 300 of its employees who have disabilities.

These businesses include the Petaluma Recycling Center on Second Street, a Senior Center for seniors with disabilities on Hunter Drive in Rohnert Park, WineBev Services on Technology Way in Napa, and Gone for Good in Fairfield. The organization also runs Old Adobe Development Services (OADS) in Petaluma, which provides employment and continuing education classes (in partnership with Santa Rosa Junior College) to help disabled students build independence and awareness of their community. All social enterprise programs offer transportation services and behavior support services. In addition, UCPNB runs thrift stores in Rohnert Park and Santa Cruz called Flipside.

UCPNB also operates the Cypress School in Petaluma, offering a personalized curriculum for students 5 to 22 years of age with autism and other disabilities. The UCPNB Boost programs serve children and adults with movement disorders.

But it’s not all work and no play for the employees of UCPNB.

“Our recreational programs are the heart of UCP of the North Bay,” says Margaret Farman, CEO of UCPNB. “From teaching a child to ride a two-wheel bike to sponsoring a weekend for our adults, we relish giving everyone an opportunity to play and have fun!

For more information about other recreational activities, visit ucpnb.org.

Wine Country Carnival

After being postponed three times due to the pandemic, the Wine Country Carnival, a fundraiser for United Cerebral Palsy of the North Bay, is set to take place on Feb. 26 at Jacuzzi Winery in Sonoma.

“Funding is always an issue, and our carnival needs sponsorships,” says Jennifer Whalen, director of community programs for UCPNB. “In the past, the carnival has always sold out, so if a company wishes to sponsor the live band or the dessert table or some of our games, we’d love to hear from you.” UCPNB participants build life-size carnival games for the event, and there’s always plenty of good food and wine.

For more information, contact Whalen at jwhalen@ucpnb.org.

Author

-

Jean Doppenberg is a lifelong journalist and the author of three guidebooks to Wine Country.

View all posts