March 2020 is etched in memory for many North Bay residents. News about SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19, had been circulating for weeks. Then, Bay Area public health officials announced shelter-in-place orders, setting in motion the first major impact locally. Schools and businesses closed, and everyday life came to a standstill in a widespread effort to stop COVID-19 from spreading. The goal was short-term preemptive action to eliminate the threat quickly, but SARs-Cov-2 is full of surprises, and two years later, the path back to normal life is elusive. Just when we feel confident that the worst is over and begin to take positive steps forward, it deals us a setback, reminding us that the pandemic isn’t over. And each time, public health officials and their staffs seek the most effective ways to keep us safe, facing new challenges as they continue to learn about an unpredictable virus while attempting to overcome shortcomings in the public health system.

Beginning of a pandemic

When early reports of a new pneumonia-like disease began filtering out of China in December 2019, local public health officials took notice. “I began actively tracking news out of China, says Lisa Santora, M.D., deputy public health officer for Marin County. However, she found that accurate information was difficult to find because the Chinese were understating the situation in the Chinese city of Wuhan, where the illness first appeared. Then, in January 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued its first warning and announced that the first case of COVID-19 in the United States had been diagnosed in a resident of Washington State who had traveled to Wuhan. Santora alerted Chief Public Health Officer Matt Willis, M.D., informing him that the novel coronavirus looked a lot like SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome), an airborne virus transmitted through small drops of saliva, which was first identified in China in 2002 and also spread worldwide. Then on Jan. 23, 2020, China closed Wuhan, a city of more than 11 million people, in a bold step that made Santora realize that SARS CoV-2 was much different from previously existing coronaviruses.

“I first heard about it in January 2020,” says Napa County Public Health Officer Karen Relucio, M.D., chief public health officer for Napa County, and it became the sole topic of discussion that month by the Association of Bay Area Health Officials, a regional network of 13 health departments that counts Napa, Marin and Sonoma counties among its members. They began discussing different scenarios for dealing with COVID-19 over the next several weeks, leading to the initial shut down in March 2020. State restrictions followed just days later, but, nonetheless, cases of COVID-19 increased rapidly, and the pandemic took hold, leading to more than 5 million cumulative confirmed cases in California and upwards of 76,000 deaths by the end of 2021, according to statistics from the state.

When Sundari Mase, M.D., Sonoma County’s public health officer, became aware of COVID-19, she had spent 18 years specializing in work on tuberculosis at the federal and international levels, and she suspected that a pandemic could be in the making. She wanted to be involved in efforts to combat it and started sending emails to public health officials to express her concern.

“That’s how I landed this position,” she says. She was well versed in tracking respiratory infections, and one of her priorities was to create a program for contact tracing with the health department’s existing nursing staff. D’Arcy Richardson, R.N., a health program management professional with extensive experience in public health and tuberculosis programs, did the training within two weeks of the county’s first case of COVID-19. Once the system was in place, the team contacted people who were infected as quickly as possible and gave them quarantine orders. “I think we were one of the first counties that were testing both symptomatic and non-symptomatic contacts,” she says.

Challenges

Mase, Relucio and Santora all recognized the threat, but public health departments were hampered by chronic underfunding and understaffing from the beginning, and the challenges were daunting. Relucio reports that public health departments were downsized considerably following the H1N1 swine flu epidemic in 2009 and 2010, leading to a long-term staffing shortage. The Affordable Care Act’s Prevention and Public Health Fund was supposed to provide funding, training and improved infrastructure. As a result of political opposition to the ACA, however, legislators cut more than $6 billion from the fund in 2017, undermining the ability of public health departments to respond to health crises. As a result, “We started off this pandemic with less staffing,” she says.

“Public health has been poorly resourced for years and years,” says Mase, explaining that when funding is flat, it’s really decreased, because costs continually go up. The underfunding meant that to obtain resources for COVID-19 programs, Sonoma County had to cobble together a team from other programs—which all suffered—until it received resources from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act. Even with funding, it takes a long time to hire and train people, and the county didn’t have a fully developed and staffed COVID section until the end of 2020.

Marin County also had too little staff to fight a pandemic, and it lacked the infrastructure for testing as well as personal protective equipment and other resources. Santora attributes decades of deficiencies in public health to chronic underfunding. “We have a cycle in our government’s history,” she says. After a big event like the terrorist attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, she explains, the government increases funding, but then reduces it when the crisis is over. Marin had a staff of six in the public health department when the pandemic began and now has more than 100. However, she doesn’t anticipate significant changes to the government’s approach. Nothing has stopped the cycle in the past, and she expects reductions in funding once the pandemic has passed because governments rarely invest in public health.

As the pandemic progressed, public health departments had to do case investigation and contact tracing, manage vaccination programs and keep track of all the information they were amassing but didn’t have adequate systems for storing so much data. The lack of adequate technology was a significant challenge. By the end of 2021, Marin County had tested tens of thousands of people and given more than 244,000 vaccinations. However, Santora points out, a public health department isn’t a healthcare system with its own data management system, and so they used Google Drive and spreadsheets at first. “We literally broke Google,” she says, explaining that people often had to get out of Google so others could access information. The county’s information technology team developed a data-management platform to handle the massive volume of information related to COVID-19 once the need became clear.

Public health departments also needed to input information into the California Immunization Registry, but such a large quantity of data all at once overburdened that system, too. “Part of the problem was that we had an antiquated state system,” says Relucio, and changing directives from the state complicated matters further. “It became this really complicated setup,” she says. When vaccines became available, she explains, the state created tiers to designate when specific occupational sectors of the population could be vaccinated, but then they changed the prioritization scheme to make it based on age. The state also appointed Blue Shield to act as a third-party provider to allocate doses, beginning March 1, 2021, but local public health had to instruct Blue Shield on how doses should be allocated. Next, the California Department of Public Health created My Turn for people to schedule appointments, forcing public health departments to learn a new system at the busiest time for vaccinations. “They kept shuffling those decks,” she says, and at a time, when they were being urged to pick up the pace and give more vaccinations, the changes slowed down the rollout.

In addition, wearing masks and vaccinations were measures meant to slow down the spread of the virus and help protect people but instead became political issues that weakened their effectiveness. Relucio explains that the politicization of a public health issue was an unexpected challenge and not part of pandemic planning, and it resulted in public health being seen in a different light, and not necessarily a positive one.

Adding to the challenges, pandemic fatigue eventually had an impact on healthcare workers and led to burnout, and a significant number of medical professionals left the field. Relucio observes that some percentage of patients with COVID-19 will have to be hospitalized, and one of the goals of the preventive measures was to keep hospitals from becoming overwhelmed with more cases of COVID-19 than they could handle. However, by the end of 2021, with the Omicron variant surging, hospital capacity was less than it was the year before as a result of staff departures and personnel ill with COVID-19 and unable to work.

Lessons

SARS CoV-2 was an unknown virus, and COVID-19 was a new disease, so they came with a learning curve. “It was challenging because there wasn’t a playbook,” says Santora. “We were constantly building the plane while flying it.”

“We learned a lot about the virus itself,” says Mase. An early discovery was that it was a respiratory virus, and because it is airborne, actions like touching doorknobs weren’t a risk as feared at first. Mutations were to be expected but were unpredictable, and so Delta and Omicron were setbacks. Omicron proved to be highly transmissible and caused the rate of infection to surge, doubling every two days at the end of 2021, upending hopes for a return to normalcy in the new year.

She also points out that the restrictions had unintended consequences. “What we did was make sure we avoided deaths,” she says. Mase acknowledges that the isolation had consequences for mental health, especially for seniors who were alone and for the businesses and industries that suffered an economic impact. In addition, she points out that the pandemic has had a disproportionate effect on vulnerable populations such as the Latino community, many of whom are essential workers. They’ve had more case rates and deaths. “It was so traumatic to see that disparity. It showed us that we really need to focus on equity,” says Mase.

“We responded the best that we could with the information we had,” says Relucio, but the lack of knowledge at the beginning of the pandemic made it impossible to predict what was going to happen. Since then, science has evolved, and “If I had the information I had now, I don’t think shutdowns would have been as extended,” she says. “We never expected it to be as difficult and constantly challenging as it has been.”

Advances

Despite the challenges, the road ahead is beginning to look brighter, thanks to safe and efficient mRNA vaccines and new treatments for those who fall ill. Prasanna Jagannathan, M.D., assistant professor of medicine (infectious diseases) and of microbiology and immunology at Stanford Hospital and Clinics, explains that if healthy people who are vaccinated become infected, the course of illness is typically mild. Vaccinated individuals who are immune-compromised or have conditions that make them high risk are more likely to become seriously ill. In that case, “If someone is newly infected and has a high risk of the disease progressing, we would administer a monoclonal antibody soon after infection,” he says.

Monoclonal antibody treatment was the only way to stop the disease from progressing until December 2021, when the FDA authorized Emergency Use Authorization for two oral medications: Pfizer’s Paxlovid and Merck’s Molnupiravir. Jagannathan reports that Molnupiravir reduced hospitalization and death by 30% in clinical trials, and Paxlovid reduced the risks by closer to 90%. He explains that Paxlovid contains a protease inhibitor, which blocks an enzyme that allows the virus to replicate, and it’s paired with ritonavir, which allows the Pfizer drug to build up in the body. “It’s an exciting result because treatment using IV was the only way before,” says Jagannathan, explaining that monoclonal antibodies are 80 to 90% effective, but must be administered intravenously in a hospital. Oral medications, on the other hand, are easier to get to patients and can be used where intravenous access isn’t available. He adds, however, “If you are eligible for treatment, what you receive would depend on which medications are available, and some medications cannot be used in particular patient populations. For example, molnupiravir is not recommended for use during pregnancy.”

Preventive treatments for people who are immunocompromised and can’t be vaccinated have also made strides forward. Jagannathan explains that patients undergoing chemotherapy or taking either steroids or high doses of anti-inflammatory medication for the treatment of conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis might not respond well to a vaccine, and some people can’t be vaccinated because they are allergic to a component. In December 2021, the FDA commissioned Emergency Use Authorization to Astra Zeneca’s Evusheld, a therapeutic that lowers the risk of infection and hospitalization significantly for those individuals.

“These are exciting developments for treatment,” he says, although how effective they will be against variants is unknown, and they will require further testing. “The virus will have a fair amount of evolution,” he says. He believes COVID-19 will eventually become an endemic disease, and SARS CoV-2 will circulate the way other coronaviruses do, once the population is fully vaccinated or has some immunity through natural infection, and the pandemic starts to recede.

The way forward

The availability of vaccines and treatments has been a game-changer, and even if new restrictions become necessary, it’s unlikely we’ll ever have to go back to the onerous conditions we faced at the beginning of the pandemic. “The writing is on the wall that there will be no more shutdowns,” says Relucio, pointing out that it’s not possible to sustain the health of people by shutting down businesses and schools because of other behaviors and health issues come into play. “You have to weigh the issues. You’re trying to balance protecting people against COVID versus protecting other aspects of physical as well as mental health,” she explains.

Santora believes that adapting to the novel coronavirus as part of our environment is the way to move forward, and it will require managing people’s fear and anxiety about transmission. Ending isolation and quarantine orders when the time is right will be one of the first steps in treating COVID-19 like a less serious disease, and testing will play a role. If a child tests positive on a Friday and then has a negative test the following Monday, for example, that child should be allowed to return to school. She acknowledges that for someone who’s been living in a pandemic for almost two years, it could be difficult to relax and let kids return to their previous routines. Access to antigen tests, though, will help us get there.

“We have to laud our public health departments. The Bay Area has been somewhat exemplary compared to other places in the country,” says Jagannathan. They’ve had to make decisions about mask mandates, for instance. “Those are really tough decisions they’ve had to make,” he says. He also credits Gov. Gavin Newsom and Mark Ghaly, M.D., secretary of the California Health and Human Services Agency, for their actions. “Their decisions have caused consternation in some populations,” he says, “but they’re doing their best to keep as many of us alive as possible so we can find the best way forward.”

Local public health officials feel privileged to serve their communities during such a difficult time. “I feel really honored that I’ve been part of this effort, and we’ve had the impact we’ve had and saved lives,” says Mase. Her hope for the future, though, is that public health departments will be better funded so that the next time a crisis strikes—whether it’s a pandemic, fire, or other disasters—they can be fully prepared.

Cases and Deaths

The California Department of Public Health provides COVID-19 Time-Series Metrics by county and state. Information reported on January 5, 2022, was the following:

California: 5,480,265 total confirmed cases of COVID-19, resulting in 76,054 total confirmed deaths

Marin County: 21.675 total confirmed cases and 251 deaths

Napa County: 15,370 total confirmed cases and 107 confirmed deaths

Sonoma County: 48,654 total confirmed cases and 410 total confirmed death

Source: California COVID-19 State Dashboard

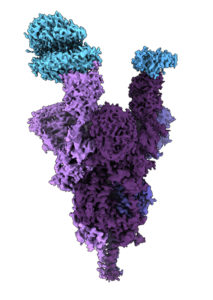

Omicron Up Close

The mutation is a natural process in the evolution of a virus, and a virus often gets weaker with successive mutations. When the Omicron variant began to surge at the end of November, however, it became clear that it was better at transmitting from one person to another than previous mutations.

To gain insight into what makes Omicron so efficient, a group of scientists at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver B.C., obtained a genetic sample of the new variant in December 2021 and conducted the first molecular-level analysis of its spike protein to find out why it’s so infectious. The virus’ spike proteins—the protrusions on its surface—bind to human cells and infect them, and UBC’s Sriram Subramanian, Ph.D., of the department of biochemistry and molecular biology at UBC’s faculty of medicine, reports that the analysis revealed 37 spike-protein mutations in Omicron, which is three to five times more than seen in any other variant of SARS CoV-2 so far, thus explaining the ease of infection.

People who have been vaccinated develop antibodies that can neutralize SARS CoV-2 and prevent it from entering cells. However, because of the large number of mutations, Omicron is effective at evading antibodies. The spike proteins also retain their ability to bind effectively with ACE2 cellular receptors, allowing them to infect human cells. “That combination of the two makes it particularly transmissible,” says Subramanian.

Studying the molecular structure gives a better understanding of how a variant works and allows the development of therapeutics to treat the illness it and future related variants cause. The best defense, though, is vaccination, which still provides protection and has been effective at preventing serious illness

Source: UBC News