The use of racist restrictions in real estate documents that prohibit the purchase, lease, or occupation of property to people of color is a piece local history that remains in many recorded housing documents today. While racially restrictive covenants are now illegal, many property owners throughout Marin live in homes that still have illegal covenants referenced in their properties’ title reports.

It’s been almost 55 years since it became illegal in the United States to place racist restrictions in real estate documents, including official property deeds. For years, the County of Marin has investigated how such language could somehow be stricken or nullified from legal documents that must be stored in perpetuity within the Marin County Recorder’s Office. The breakthrough came with January 1, 2022, passage of California’s Assembly Bill (AB) 1466[External], requiring all county recorders to redact illegal restrictive language.

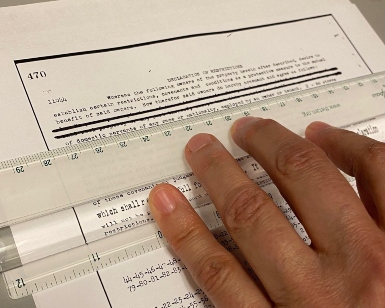

On October 25, staff from the Recorder’s Office–led by Assessor-Recorder-County Clerk Shelly Scott–provided an update on the ongoing effort to comply with AB 1466, called the Restrictive Covenant Project. And while previously it had been illegal to alter language in official legal recordings, now the staff is recording modifications that include a redacted copy of the original document. Black pens are being used to redact the racist passages and note that it was updated.

Watch the County’s video[Video] about the project.

Discovering the now-illegal language is not a quick process. In fact, it’s expected to take years to complete the task. The Recorder’s staff welcomes help from homeowners, who can check their documents provided by a title company during a purchase transaction. Anyone living in a home built in the mid-1960s or earlier can examine their title papers and email the Recorder’s Office staff if the racist restrictive covenants are found.

“Finding those passages in historic documents is very hard because of our statewide traditional filing system that goes back more than a century, so it’s like the proverbial needle in the haystack,” said Jodi Olson, Chief Deputy Recorder. “I’m proud of the meticulous work our team has done thus far and we’ll be diligent about rectifying these recordings no matter how long it takes.”

Speaking before the Board, Scott said Board President Katie Rice approached her about addressing restrictive covenants several years ago after Rice had discovered racist language in her own home deed.

“I felt that doing this work is really meaningful, important and educational,” Scott said. “Housing is not only a local, regional, and national conversation, but we need to make sure we are looking at the past so we don’t repeat those mistakes. Our staff is really proud of the work we’re doing.”

ARCC’s Restrictive Covenant Team has reviewed about 1,550 recorded documents in its search for illegal language and mapped those parcels with the assistance of the County’s Information Services and Technology (IST) Department and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) specialists. The team identified 800 parcels on which the deed modifications need to be made and have completed 55 of them.

All document modifications made thus far by ARCC staff involve race-related restrictions, but some restrictions from past decades prohibited the purchase, lease, or occupation of properties based on gender, marital status, age, source of income, and other characteristics. All the limitations became illegal with the passage of the federal Fair Housing Act of 1968, which blocked loopholes in the larger Civil Rights Act of 1964.

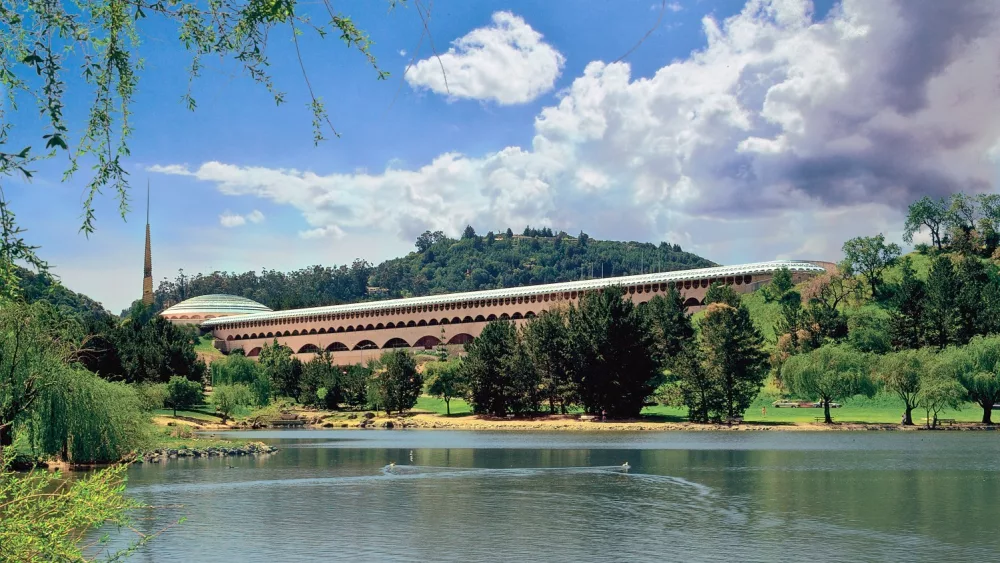

Scott said roughly 8,500 homes were built in Marin from the time the racist language was legalized in 1926 and 1948, the year the U.S. Supreme Court declared it a violation of the 14th Amendment. As Marin’s subdivisions were planned and built during the Baby Boom years, its population more than doubled between 1948 and 1968 when the Fair Housing Act was passed.

“It’s so important that our larger community understand the uncomfortable truths about residential segregation and racist institutional practices that lifted up some and left so many others behind.” Rice said. “That is the basis for a lot of the poverty in our community and others across the country today.”