If you don’t live there, you may think of American Canyon as somewhere you go through to get somewhere else—a thoroughfare, a stretch of congestion as you speed north or south on Highway 29. But the City of American Canyon cannot be seen from the road. American Canyon is, and has been since it was incorporated in 1992, home to a vibrant, engaged, diverse people who share a sense of place and community and a dream of greater community that is right now on the verge of coming true. But before we get to that, we need to find the City of American Canyon in a way that you can’t find on a map.

As we start our journey through American Canyon, we’re invited to take a trip back in time with local historian Fran Lemos. She came to the area 70 years ago as a bride, and with her new husband built a house at the base of Oat Hill, where she resides to this day. Riding with us on the tour is American Canyon City Council member Mark Joseph, who has been on the council for 30 years. Joseph says he considers Fran to be something like the founding mother of the community. “She’s always been here. She has been such a champion of the community,” he says. “She’s one of the last of the original people who championed American Canyon. I call her the Queen of the City, or the Matriarch. She’s almost an icon in the community.”

Back in the day

Napa Junction, once an industrial center for building materials, is barely a memory now, other than the name on a nearby road sign. Today, hopes for a new life for the area are pinned on a certain piece of land where once stood a cement plant. In the early 1900s, the Napa Junction Company, owned by one Augustus Watson, was at the height of its productivity–extracting and shipping 30 tons of limestone a day, via the Southern Pacific Railroad, to nearby cities to be made into concrete. By 1902, Watson sold the plant to the Standard Portland Cement Company, which later became a major supplier of cement to help rebuild San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake. In its final industrial incarnation, the plant was sold in 1950 to the Basalt Rock Company, which supplied aggregate to form concrete to build Bay Area skyscrapers. By the late 1970s, when the limestone on the land was exhausted, the plant shut down. The land languished and buildings fell into disrepair. In 1985, local winemakers, the Jaeger family, purchased the land for vineyards, but it proved inhospitable for grapes. So the land settled back into nature and the place, which had produced so much industry over a century ago, went quietly to ruins.

Cruising with Fran through American Canyon neighborhoods, one can sense this growth–like unwinding a time machine–starting with the modest, closely spaced subdivisions built for World War II veterans and their families, on through newer neighborhoods of medium-sized homes, and then into the more recent developments featuring larger, more commodious houses with green lawns and striking views. Unlike what you see of American Canyon from Highway 29, the neighborhoods have vistas, views, parks and small open spaces. And these neighborhoods, diverse in their economic stature, seem comfortable as a community. Are they?

“People love living here,” Fran says. “Everyone gets along.”

A young and growing community

Fran is an excellent driver. Careful of speeding traffic, she smoothly swings over to the east side of the freeway, toward the 620-acre Newell Open Space Preserve. There she shows us newer home developments, including American Canyon High School which, built in 2010, looks vast and modern. American Canyon boasts five schools: Three elementary schools, a middle school and the high school. Unlike other areas in Napa County, where aging populations and high percentages of second and third homes are associated with falling enrollment rates, school enrollment in American Canyon remains steady–– and diverse. According to one school district survey, there are more than 38 languages spoken in American Canyon–a cultural mix of Asian, East Asian, Hispanic, Pacific Islanders, Alaskan Native as well as standard English learners. As we drive through the shopping centers on Fran’s tour, we see restaurants that hint of this diversity. Mark Joseph points out a couple of favorites––a Nepalese fusion, an Indian grill, a Chinese eatery, and a tidy new Italian restaurant where they make their own pasta. If you want French pastry, he says, you can go back over to the west side, to Paris––“Le Paris,” that is––where the goodies are gorgeous, and you can take a bag home. All this, plus acres of housing, and more on the drawing boards, calls into questions of water sustainability in a time of drought.

Water

Water is a constant on people’s minds. In an earlier conversation, City Manager Jason Holley told us that the City of American Canyon is trying to use water in the most efficient ways possible, including converting the parks and grassy area irrigation systems to recycled water. To do that, American Canyon has embraced cutting edge water practices. “In a lot of our new developments,” he says, “particularly our mixed-use developments, we do [potable] water, waste-water and recycled water. We provide all those utilities for our residences and businesses. In a lot of our new developments, we’re flushing toilets with recycled water.” So instead of taking high-quality drinking water and flushing it down the toilet, they’re flushing with recycled water. “That’s very leading edge,” he says, “particularly for the North Bay. We’re using water twice and three and four times.”

It would seem that the City of American Canyon has everything families and neighborhoods need. But there’s one crucial element missing. It’s what the people of American Canyon have been talking about since their incorporation as a city: a “town center.” A place where people can gather, meet a friend, have coffee, dinner, do a little shopping and welcome visitors for events. A place that would give the City of American Canyon an identity.

Establishing an identity

According to City Manager Holley, a city’s identity starts with its community. “What makes a city is the people,” he says. “It’s the collective.”

The City of American Canyon is growing. Back in 1992, when the city became incorporated, the population was about 7,000; now it’s nearly 22,000. “There’s been closely a threefold increase,” he says. “And that group has chosen to be in American Canyon.” Why? The reasons are obvious once you get to know the place, he says.

“There’s a pretty deep pride in the community,” Holley says. “And a desire to make it a great place.”

That desire is now wrapped up in the promise of the 309-acre Watson Ranch Project, currently being built in and around the ruins of the once-thriving cement plant in the former Napa Junction. For that old, industrial piece of land, a major transformation is in process. “It will become the town center,” says Holley. “I think that’s a shared dream.”

The vision of the Watson Ranch

The Watson Ranch project is a careful balance of vision and meticulous on-the-ground planning. “The project will be unlike anything in the Bay Area that we’re aware of,” says Holley. “It’s essentially a master-planned community.”

To get a sense of how all this will work, Holley suggests we meet the Watson Ranch developer, Terrence McGrath. He says McGrath has been working on the entitlements for Watson Ranch since 2004. That’s the year McGrath, whose company, McGrath Properties, which specializes in developing “underutilized” properties, partnered with the Jaeger family, which had owned the property since 1983. “But then came the recession,” says Holley. “So a lot of things came to a screeching halt, but then the project started up again and Terry’s been the big mover for this project from then on.” Over time, McGrath and his team worked with city officials to bring their town center and Ruins and Gardens idea into focus. The Watson Ranch Specific Plan was unanimously approved by the American Canyon City Council in 2018 and is now an integral part of the city’s Strategic Plan.

Touring the Watson Ranch

When we met with Terrence McGrath, the site–all beige-colored, 309 acres of it–was quiet. The ground looked like those dirt patches little boys like to play in, charging their toy trucks up imaginary roads and down hills and along flatlands, making tracks around and under things. McGrath, with that kind of focused enthusiasm, can’t wait to get going. As soon as our seatbelt buckles snap shut, he takes off up a dirt hillside, around a newly paved roundabout, over newly graded dirt road. “See there ––” he shouts over the sound of the motor, “all the underground work has been completed.” All the utilities, water pipes (potable, sewer, recycling, and stormwater) are now safely underground and the market-rate lots are ready for houses, a milestone for the project.

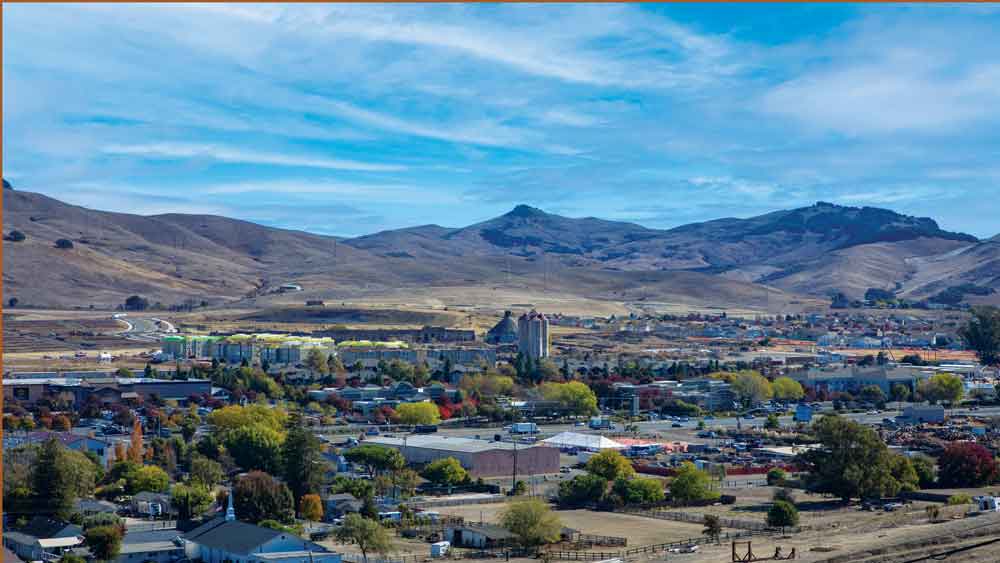

As we’re taking in the enormity of the scene, McGrath heads to the top of a hill and stops. From here, looking west, we can see an amazing view––the glitter of the Napa River and the wetlands, and beyond that, the blue outline of Marin’s Mt. Tamalpais. A little farther to the south, barely visible, is the Golden Gate Bridge. Looking east, we get the soft rolling hills of the Newell Open Space land that runs along the eastern border of the Watson Ranch. It’s a huge project. How does he hold a project of this scope in his mind?

McGrath puts the car in gear and acknowledges that, yes, this is a huge project. He says that you can’t do it all on a “chalkboard.” You’ve got to get out there on the ground–walk around in different times of day, different seasons, different weather. Listen to what the land is telling you. As to the concepts, he spends time watching people in public places, what they do, what they like, where they gravitate to. He looks at what else has been successful, like V. Sattui Winery in St. Helena, Oxbow Market in Napa, Pier 39 in San Francisco—places where people mix and meander and enjoy diverse experiences. As a developer, he has a team of designers. But this walking around, watching, listening—it’s the way an artist thinks; it allows him to plan for the long run.

For example, he says that at first he’d wanted the hotel to be up on top of the hill. But now he doesn’t want anything on the top of the hill. The hotel will go down on the flat part of the site, near the ruins; that way, everyone will get a beautiful view.

Back in the car, he takes us off around a corner and down a steep, rock-strewn dirt path through some underbrush, pulling to a halt at the edge of a steep quarry—it’s like being in a car ad.

He hops out of the SUV and strides to the edge of the quarry, motioning beyond. “Can you imagine this as an amphitheater?” Seeing him standing there, presiding over the imaginary multitude, one can almost see the people enjoying themselves around this natural feature, under the stars on a summer night, with music filling the air and the whole place coming alive. It’s a fun moment, but he’s deeply serious. McGrath firmly intends for this to happen. Plus, he explains, the quarry will be part of a water conservation program––the development’s natural water reclamation feature. When it rains, water will fill up the quarry pond and gradually seep into the ground to be used as recycled water. Watson Ranch, like the rest of the City of American Canyon, is planning a whole recycling system around a scarcity of water. With 1,200 housing units going in, plus restaurants and the rest, efficiency–in water and everything else–is crucial.

Next, we drive by a group of rectangular boxcar-type structures covered in yellow–the affordable housing modules, already delivered and installed. He talks about how this housing is cost effective because of its modular construction. Materials are still materials–wood is still wood–but the mode of construction can be far more efficient than normal, reducing overall costs. The units were made in Idaho, fabricated using a sophisticated robot technology and delivered practically ready-for-move-in, with the appliances already installed.

The market-rate lots are ready for building and, so far, 20 have been sold, McGrath says. They, too, will be extremely efficient. Both housing types will be solar-ready. And then there’s the big draw: the Ruins.

The Ruins

For those who have only seen “the Ruins” from afar, the place is crazy wonderful. It’s an entire environment, in wild and sumptuous colors, impossible forms. The forms are tall and covered in emotion-driven, and often beautiful, graffiti art. You feel you’ve stepped into another world. It’s not the ruins of a 12th century monastery, as you’d see in England–it’s just what’s left of an old cement plant opened in the 19th century, but still, there’s a feeling of mystery. Even if it’s just the American industrial past–it’s a place where people labored and made stuff. And this is what remains–concrete walls covered in wild, spray-painted graffiti, made mostly by the developer’s friends. (McGrath also points out several walls that were painted in October by over 30 women artists of color who are part of a national organization called Few and Far.) There’s a feeling of music and rhythm as you move from one unique space to another.

For more information on American Canyon and the Watson Ranch project, visit the city website at cityofamericancanyon.org.

National Survey results

A 2022 National Survey funded by the City of American Canyon shows that a representative sample of residents feel positive about where they live.

The survey was done over a period of seven weeks, and offered in English, Spanish and Tagalog. Mailings inviting participation reached 2,668 households of which 335 completed the survey.

Of these, nearly 70 percent gave positive evaluations to the overall quality of services provided by the city, similar to comparison communities across the nation, and, overall––83 percent––of the respondents view the city as a good or excellent place to live.

https://www.cityofamericancanyon.org/community/national-community-survey

Learning More about Watson Ranch Resources

* More on the Watson Ranch Project, and to view the Watson Ranch Specific Plan, visit cityofamericancanyon.org.

* Don’t miss the video by the developer showing the scope of the project in the construction stage. Visit youtube.com and search for Watson Ranch.

Between this drone’s view of the actual project underway and the detailed presentation by the City’s Watson Ranch Specific Plan, it’s possible to see why some in American Canyon are excited.

Queen of the City

Whether Watson Ranch puts American Canyon “on the map” or not, one thing is certain—the project has already put Fran Lemos on the map. The project’s 183-unit, three-story apartment complex Lemos Pointe, is named for the longtime American Canyon resident and advocate, who arrived as a newlywed nearly 70 years ago and never left. And its address? 1 Fran Lemos Lane.