In a world where many species are rapidly going extinct, amphibians are at the greatest risk.

Their moist, permeable skin makes them particularly susceptible to drought and toxins. They are an “indicator species,” providing valuable insight into changes in an ecosystem. California newts (Tarichoa torosa) are endemic to the state, yet their numbers are dwindling. Populations in southern California have suffered declines due to loss of habitat and from the introduction of predatory fish, crayfish and bullfrogs, which eat the larvae and eggs. Ponds have been eradicated for development, and streams destroyed by sedimentation resulting from wildfires. In San Diego County, the California newt has gone extinct.

In northwest Marin County, however, they face a particularly unique challenge.

During the rainy season, newts venture out of the hills and cross Chileno Valley Road en route to their Laguna Lake spawning grounds. Many get run over by cars and trucks and never make it. Other amphibians get run over too.

Distressed by the carnage, local rancher Sally Gale formed the Chileno Valley Newt Brigade—whose volunteers gather at night to scour the road by flashlight. They scoop up the slow-moving creatures and transport them across to safety. The volunteers’ efforts are timely. In January, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) reclassified the California newt from Least Concern to Near Threatened. Volunteers on the road are only a temporary fix. A more permanent solution is needed.

On a dark and stormy night

Bypassed by Bay Area urban sprawl, Chileno Valley is all about space and sky and land.

Hills roll toward a distant horizon. Black Angus cattle, cows and sheep dot the landscape. Ranchers operate spreads of 500 to 1,000 acres, maintaining a farming tradition passed on through generations. Many of these ranchers are descended from Swiss immigrant Charles Martin (nee Carlo Martinoia) who arrived in the United States in 1856. He prospected for gold in the Sierras and worked in agriculture on the Monterey peninsula prior to purchasing over 2,000 acres of Chileno Valley farmland. There he became a dairyman, prominent banker and businessman. Martin is Sally Gale’s great-great grandfather. Though Gale, 80, didn’t grow up in Chileno Valley, she and her husband Mike returned to the family property in 1993. “With our three children grown, we felt the ranch pulling us home,” she says. The couple restored Martin’s once-grand, two-story 1885 Italianate-style farmhouse where he lived with his wife and seven children. The Gales mended fences, restored water systems, creeks and native woodlands. They planted 400 apple trees, started a grass-fed beef business, and have served as board members of such local organizations as Marin Agricultural Land Trust (MALT), Marin Resource Conservation District, Marin Organic, Marin County Farm Bureau, Marin Conservation League and Marin Farmers Market. In 2000, they entered into an agricultural conservation easement with MALT to permanently protect their 586-acre ranch from development, while preserving the land for agricultural purposes.

As a rancher concerned about the environment, it seemed only natural that Sally would be drawn to saving the newts. “On a rainy night four years ago, Mike and I were driving home from having dinner with friends,” she says. “I spotted newts on the road and asked him to stop. I got out and started walking. I counted 45 dead newts. I moved five live ones across to safety. I knew I had to do something to help them.”

Newts vs. humans, tires

California newts are winsome creatures. They have an orange underbelly, protruding eyes, small feet with toes, and a straight-lined mouth slightly curved in a smile. Their beguiling looks can be deceiving. They are highly toxic, though not toxic to the touch. They have few predators, an exception being the garter snake that’s developed immunity and seeks newts out for nourishment. The bigger threat comes from humans encroaching on their habitat. Or running them over.

Newts, a type of salamander, are both terrestrial and aquatic. They can live for up to 30 years. A native species, they feed on mosquito larvae, worms, snails, slugs and sow bugs. They keep nuisance species, which can alter the balance of an ecosystem, in check. U.S. Fish and Wildlife biologist Susan Jewell is quoted in a 2022 article published by the United States Geological Survey’s Office of Communication and Publishing, as saying: “If we lose salamanders, we lose an important part of what keeps many of our forests and aquatic ecosystems vital, along with the benefits those ecosystems provide for the American people.”

A newt lease on life

Chileno Valley’s 200-acre, privately owned, Laguna Lake is a vital valley resource. Its shallow waters support ranching and is used for crop irrigation. It’s also the newts’ spawning ground. Beginning in the autumn rainy season, newts cross a mile stretch of Chileno Valley Road to breed at Laguna Lake—and cross it again on their late-winter return to woodland areas with their young. After sighting dead newts on the road four years ago, Gale contacted her friend Gail Seymour, retired senior environmental scientist with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. Together they founded the Chileno Valley Newt Brigade. They obtained grants of $1,000 each from the Tomales Bay Watershed Council and Marin County Fish and Wildlife to purchase road-safety equipment. And they put out a call for volunteers.

“To draw a crowd for our first orientation, I cooked up a batch of chili and invited David Herlocker, a Marin County naturalist, to speak,” Gale says. Approximately 30 people from around the Bay Area attended. “Though there was a good turnout, it took a while for the brigade to gain traction,” Seymour says. “The first year there were only eight of us on the road.”

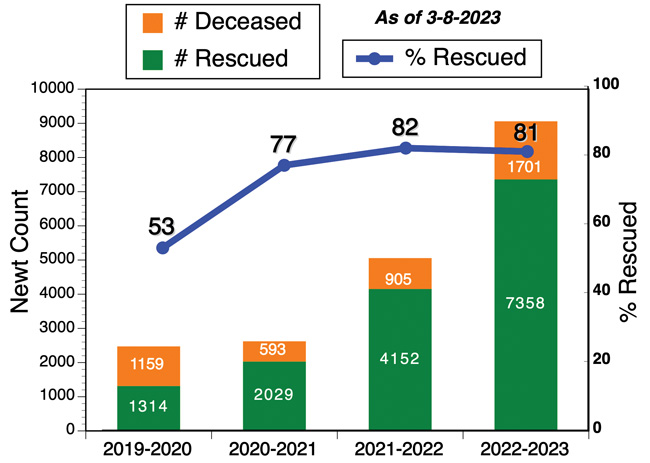

Word spread. Now there are 75 active volunteers. The greater the number of volunteers, the more newts saved. That’s reflected in the statistics. During the 2019-2020 season, the brigade saved 1, 314 newts—compared to 7,179 so far this year. And the percentage of rescued—82% versus 53% —improved, too.

Volunteers receive training in road safety and the use of the iNaturalist app. “First time out they’re paired with an experienced brigadier,” Gale says.

Volunteers wear reflective vests and carry flashlights. They cover two-hour shifts from 4:30 to 8 p.m. Coastal oaks and bay trees shade the side of the road where the newts spend most of their time hunkered down under logs. On the other side is Laguna Lake where the newts breed. Chileno Valley Road separates their habitats. Though mostly quiet during the day, at commuter time, just as the newts begin to emerge, traffic picks up. Signs are placed at either end, alerting motorist to brigadiers on the road and newts crossing. When the cars approach, volunteers step well off the road, face the traffic and point their flashlights to the ground. Most motorists slow down, are courteous and curious.

Collecting data is an important aspect of what the volunteers do. Newts and the other amphibians are photographed. The photos, along with other pertinent information, are uploaded to iNaturalist, the popular citizen-science network used for sharing observations of the natural world. Brigadiers record the date and time of observation, the species type, adult or juvenile and whether dead or alive. The observations, together with GPS coordinates, can be analyzed to determine migration patterns and population trends.

Liza Eichert, principal at Mary Collins School at Cherry Valley in Petaluma, captains the eight-volunteer, Saturday night team. They meet at the Gales’ barn to gather equipment and review road-safety procedures before heading out. “We never know what to expect,” Eichert says. “There can be only a few newts on the road or a lot. One night we saved nearly 1,000 juveniles coming from the lake headed to the woods. Some were so tiny you could barely see them.” Eichert’s passion for nature extends to her role as an educator. “I encourage students to walk the school’s nature trail, go on field trips and participate in the Point Blue’s wonderful conservation science program, “Students and Teachers Restoring a Watershed (STRAW),” she says about the Marin/Petaluma-based conservation nonprofit. Two other teachers from Petaluma City Schools, Kirsten Franklin and Kerry Sanita, are also brigade volunteers.

Volunteer Craig Erridge makes the 45-minute drive from Sonoma on Tuesday nights. “I became fascinated with herpetology at an early age. I still am. I enjoy being out on the road with others concerned about the environment and saving creatures,” he says. “Newts venture out of the forest during spawning season for a little love on the other side of the road only to get squashed by a motorist in a hurry to get home to watch Jeopardy. Just doesn’t seem right. Least I can do is help them make it across.” Erridge, retired after 30 years in the computer industry, spends time camping and involved in other outdoor activities. “There are few places one can go these days without hearing the rumble of civilization in the distance. Chileno Valley is special. Walking the road at night after nature settles in, there’s only the sound of silence.”

Wildlife crossings are the new black

The implementation of wildlife crossings has become a global trend. The concept first took hold in the 1950s in France. The Netherlands took the lead with 600 wildlife overpasses and ecoducts throughout the country. Canada’s Banff National Park has 44 wildlife crossings including six overpasses and 44 under the road. Other countries have adapted ingenious solutions to fit the species and the threat. West Japan Railways, in collaboration with the Suma Aqualife Park aquarium in Kobe, installed shallow tunnels allowing turtles to cross under the tracks. In October or November, millions of Australia’s Christmas Island large red crabs migrate to the sea to spawn. Underpasses and bridges built over sections of the road ensure safe passage. In Costa Rica a roadway constructed through the rainforest bisected the howler monkey’s habitat. Many got killed by speeding vehicles or electrocuted swinging on power lines in attempting to cross. Rope bridges connecting overhead forest canopies provided the solution. Howler monkey road kill declined and the population rebounded.

The U.S. has lagged the rest of the world in addressing wildlife crossings, though things are beginning to happen. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 provides $350 million to be distributed over five years for the construction of safe wildlife passage over or under federal highways. Last year California Gov. Gavin Newsom signed the Safe Road and Wildlife Connectivity Bill. State agencies will be required to include wildlife passage solutions in road projects. According to a UC Davis Ecology Center report, more than 44,000 wildlife-vehicle collisions occurred in California from 2016 to 2020. The collisions resulted in injuries and deaths to drivers and wildlife and caused at least $1 billion in damages.

At Liberty Canyon, about 40 miles outside Los Angeles, the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing is under construction. When completed the crossing will span a 10-lane stretch of Highway 101 and reconnect pockets of isolated mountain lions. Without gene pool diversity, scientific studies project that Los Angeles County’s mountain lions could go extinct in the next 50 years. When completed the $100 million project will be the largest of its kind in the world. Landscaped with native vegetation and pollinator plants, the structure will provide a crossing not only for mountain lions but bobcats, coyotes, badgers and skunks, as well as other wildlife.

Though large mammals tend to garner the most attention, amphibians have a following, too. A Yosemite National Park road separates the rare Yosemite toad from its wetland breeding habitat. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in partnership with Caltrans, United States Geological Survey and the U.S. Forest Service erected an elevated wooden span so the Yosemite toad and other amphibians could pass underneath. During spawning season in North Amherst, Massachusetts, spotted salamanders cross Henry Street to reach vernal pools on the other side. Residents carried them across to safety. On hearing about those volunteers’ efforts and plight of the salamanders, the British Fauna and Floral Preservation Society, together with Germany’s ACO Polymer, funded an experimental tunnel. Subsequently the Hitchcock Center for the Environment, Amherst Department of Public Works, University of Massachusetts, Massachusetts Audubon Society and local residents collaborated to build two tunnels with drift nets to steer the salamanders toward the openings. And landowners allowed the project to be built on their property. Completed in 1987, the Henry Street tunnels became the first amphibian passages in the United States.

Similar to the residents of Henry Street, the Chileno Valley Newt Brigade is working toward a permanent solution. “Together with our neighbors, the county and other conservation groups, we hope to implement a science-based crossing to ensure safe passage for amphibians and other creatures,” Gale says. Currently the brigade is seeking grants and donations to fund an engineering and biological feasibility study to evaluate crossing alternatives. Data collected by the brigade over the past four years will be an important source of information for use in the evaluation.

A quote from Robin Wall Kimmerer’s book, “Braiding Sweetgrass,” perhaps best expresses the sentiment of the Chileno Valley Newt Brigade and the many others involved in amphibian conservation:

“Each time we rescue slippery, spotted beings we attest to their right to be, to believe in the sovereign territory of their own lives. Carrying salamanders to safety also helps us to remember the covenant of reciprocity, the mutual responsibility that we have for each other.”

Those wishing to volunteer can go to the brigade website chilenovalleynewtbrigade.org and fill out an application.

Laguna Lake, a vital 200-acre ecosystem

Laguna Lake isn’t only popular with newts. Located along the Pacific Flyway, many species of birds call the lake home. Dede Sabbag, a birder for over 45 years, is a volunteer involved in updating the Marin County Breeding Bird Atlas. “eBird lists 146 bird species at Laguna Lake,” she says. More than 100 million sightings are recorded on eBird each year by birders around the globe. In January 2022, an eBirder observed 12,000 ringed-neck ducks and 8,000 lesser scaup at Laguna Lake. Both species are divers and tend to hang out in the lake’s deeper water.

Over the summer songbirds migrate to the lake from Mexico and populate vegetation along the shore. In the winter, geese and ducks arrive from Canada, Alaska, Washington, Montana and Idaho. In spring birds gather to nest and raise their young. And there’s an array of raptors—the bald eagle, golden eagle, hawks, falcons and owls. “This year’s unusual sightings include a snow goose, a tundra swan and a sandhill crane,” Sabbag says. The lake’s invertebrates and microorganisms form the basis of a food chain for many creatures.

Laguna Lake is part of a dynamic ecosystem. Yet in 2021, the lake dried up. The absence of water can have devastating consequences. The natural lake’s water is a source of life for wildlife, birds, amphibians, invertebrates and plants. Ranchers rely on the lake for their livelihoods. The following year the rains came and the lake filled up. The rains, they need to keep a fallin.’ So much is at stake.

9 thoughts on “Caution: Newt X-ing”

I love the valuable info you supply in your posts. I will remember this.

An attention-grabbing dialogue is value comment. I’m sure that its better to write on this topic, towards the often be a taboo topic but typically persons are not sufficient to speak on such topics. To another location. Cheers

right on our supermarket, i can buy some cheap protein bars which i always consume when doing workouts,

I don’t like your template but your posts are quite great so I will check back! Also i can’t join to your rss feed! Any ideea why?

It’s hard to find knowledgeable men and women for this topic, however, you seem like do you know what you’re preaching about! Thanks

Nice read, I just passed this onto a colleague who was doing some research on that. And he just bought me lunch since I found it for him smile Thus let me rephrase that: Thank you for lunch!

Phlebotomy Certification Ever before discovered of phlebotomy certification? Superior even now, ever before observed of phlebotomy? Certainly, it is not a typical phrase you hear approximately. In case, you will be thinking what it really is, phlebotomy is often a process by way of which blood is removed by implies of a needle. You may possibly be pondering, are not these folks called nurses? Nicely, no. Nurses can perform phlebotomy but not all phlebotomists are nurses. People that are qualified only to take away blood with a needle are known as phlebotomists, they as well perform in hospitals and clinics but which is all the health-related help they can supply unless theyre prepared for much more.

i love bob dylan, he is one of the best singer songwriter**

Can I say what a relief to discover one who actually knows what theyre preaching about on-line. You certainly understand how to bring a challenge to light making it important. More and more people really need to check out this and understand why side of your story. I cant believe youre less well-known simply because you undoubtedly develop the gift.