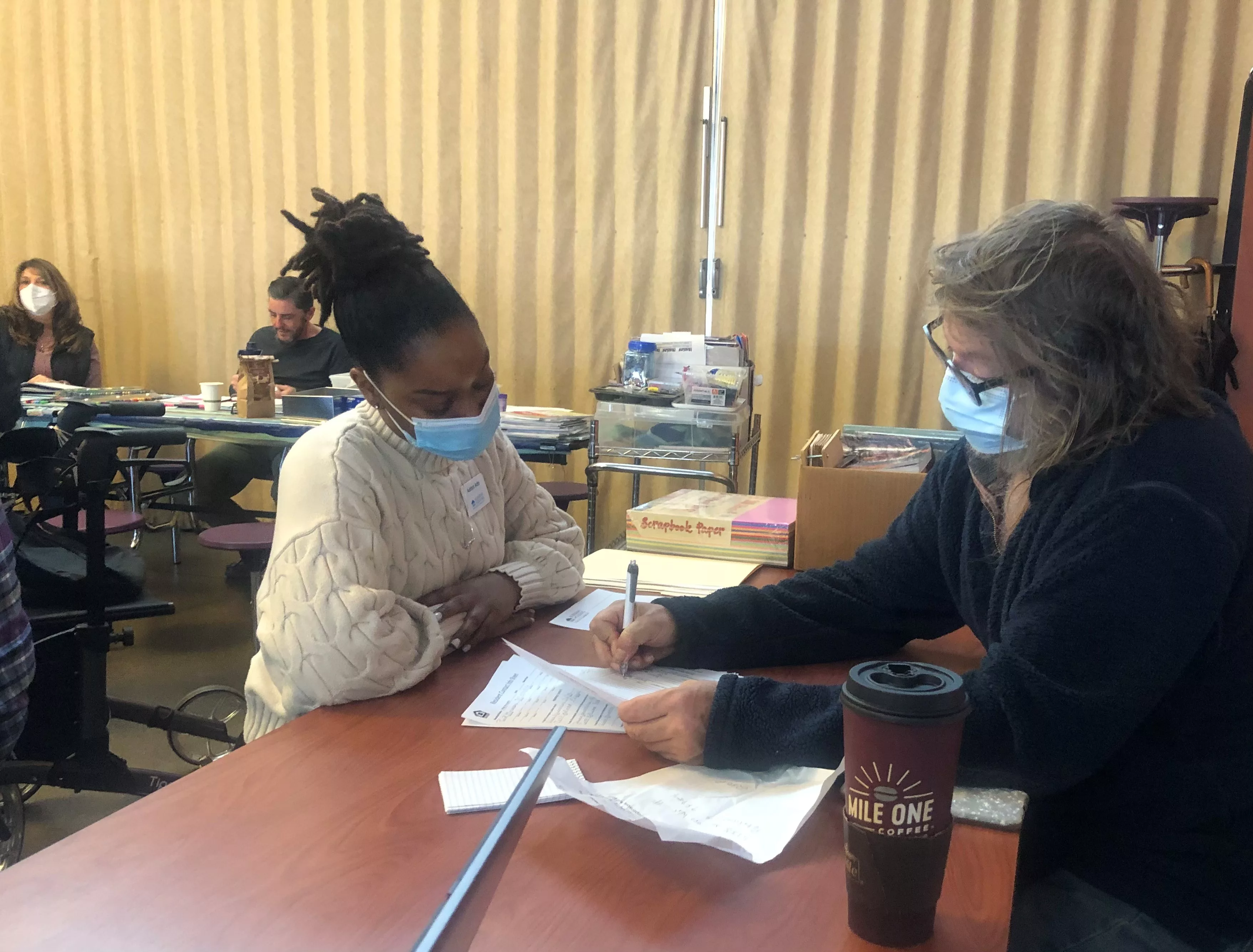

Social Advocates for Youth Finley Dream Center in Bennett Valley, which serves transitional age youth experiencing homelessness. [Photo courtesy Social Advocates for Youth]

As the North Bay’s nonprofits and government agencies prepare shelters and warming centers for winter, they want to share that one of the reasons the number of people experiencing homelessness has not dropped significantly is because new individuals and families lose housing on a regular basis. The North Bay has a high average cost for rent and local wages do not average as high as those in other parts of the Bay Area. In addition, there has been an 8.7% increase in the cost of living in the U.S. since 2022. Another concern is that Sonoma County, which currently has the highest population of people experiencing homelessness in the tri-county area, has been challenged by a multi-month lag in paying nonprofits to help people in need.

Given these ongoing strains, more people in the North Bay will likely lose housing this winter. The situation will be alleviated if people who are housing-insecure or experiencing homelessness come forward to request rent subsidies or nonprofits can identify and assist housing-insecure individuals before eviction. Nonprofits can offer other assistance—including utility subsidies, food, clothing, laundry and showers—to help people focus spending on rent or mortgage payments.

“The longer people wait to get help, the more desperate they are. That is why we try to get people connected to resources before they are evicted. We don’t want to see them lose their belongings and feel their only option is to live in a vehicle or encampment,” says Fordham.

Other tools to assist people experiencing homelessness include more funding for beds in substance use treatment centers, more vouchers to subsidize rent payments, more supportive services like workforce training programs, and more housing units.

“Even people with significant impairments, who chronically experience homelessness [defined as experiencing homelessness for over one year] and have concerns like a serious disability, usually benefit from permanent housing with voluntary supportive services,” says Chris Cabral, CEO of Committee on the Shelterless (COTS). COTS is a Petaluma-based nonprofit that offers housing for single adults, families and veterans.

This type of housing, called permanent supportive housing (PSH), combines affordable housing with on-site support staff and visiting staff who offer access to services like introductions to work opportunities. A 2020 UCSF study found less than 5% of people offered PSH return to homelessness.

Cabral says the North Bay does not currently have enough PSH for the individuals who are chronically homeless.

“It can take up to six months to find a bed in a detox unit. Patterns like substance use and chronic homelessness are linked. More money for substance use recovery could open up more spots in PSH,” says Cabral.

Laurel Hill is the director of safety net services of Community Action Marin (CAM), a San Rafael-based nonprofit that provides outreach, housing case management, and rental assistance to people experiencing homelessness. Hill says that an increasing number of people are becoming unhoused due to rising rents and residual economic impacts of COVID-19.

“For example, the line of RVs on Binford Road in Novato started ballooning during the COVID-19 pandemic. It’s now over 100 vehicles,” says Hill about the Highway 101-adjacent road that has made national headlines due to its plethora of unhoused people living in vehicles. “The biggest challenge facing those individuals and the agencies that are trying to assist them in becoming rehoused is the lack of both subsidized and affordable housing in Marin.”

Seniors falling into homelessness

Adults aged 65 and older are the fastest growing age group who are becoming homeless, according to a 2019 report by University of Pennsylvania researchers on homelessness in Los Angeles County, Boston and New York City. This trend is echoed in the North Bay’s three counties, according to data and eyewitness accounts from local nonprofits.

“We are seeing people in their 80s and 90s end up in a congregate [group] homeless shelter for the first time. This does not allow them to get good sleep or recover from medical issues associated with aging,” says Fordham.

Cabral says over 35% of the population that COTS sees is over 55.

Jennielynn Holmes, is CEO of Catholic Charities of the Diocese of Santa Rosa, a nonprofit that aids people in need and operates across six counties in northern California, including Napa and Sonoma counties. Holmes says Catholic Charities is partnering with cities to ensure seniors and other people experiencing homelessness remain in the counties where they currently live. There is not a plan to assist individuals with relocating to areas with lower costs of living.

Kelli Kuykendall, housing and community services manager of homeless services for the City of Santa Rosa, verifies that the goal is to help people experiencing homelessness get local housing they can keep.

A person experiencing homelessness and their friends and family members benefit from this solution. Usually, a person experiencing homelessness has identified sources that will help them here, like doctors or parents.

“The individual’s friends and relatives also experience relief. It can be stressful for a parent or friend to have the person at risk move several hours away to an unfamiliar place. There it’s difficult to check in with them or offer food or a hot shower,” says Kuykendall.

Usually, the majority of people experiencing homelessness are from the area where they currently reside. For example, Sonoma County’s 2023 Homeless Point In Time Count showed that 85% of people experiencing homelessness lived in Sonoma County before they lost housing. Yet there are some circumstances in which people experiencing homelessness in one spot seek services in another.

Nathalia Zavala is the program specialist and executive assistant for Sonoma Overnight Support, a Sonoma-based nonprofit that offers meals, showers and laundry services to people experiencing homelessness.

Marin County-based families of people with serious mental illness (SMI) have on occasion set up housing for a relative in Sonoma County. This is because the cost of living is lower in Sonoma County, says Mary-Frances Walsh, executive director of NAMI Sonoma County, a chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness. NAMI Sonoma County is the Santa Rosa-based office of a national organization that supports individuals and families affected by serious mental illness.

One more local outlier is that people experiencing homelessness in West Marin frequently seek services in Petaluma. This is because it is easier to travel between West Marin and Petaluma than between West Marin and San Rafael.

No significant changes in the numbers

Across the North Bay, populations experiencing homelessness have remained relatively stable since 2022. Most data come from the three counties’ 2022 and 2023 Point in Time (PIT) Counts, which tally the total number of people experiencing homelessness in a county on a single, predetermined day.

The most recent PIT Counts show Marin County had 1,121 people experiencing homelessness in 2022, up from 1,034 in 2019 ; Napa County had 506 people experiencing homelessness in 2023, up from 494 in 2022, and Sonoma County had 2,266 people experiencing homelessness in 2023, down from 2,893 in 2022.

While offering services during a PIT Count and afterward, nonprofit staff have learned the reasons for losing housing include rent increases, job loss and disabling conditions —long-term physical or mental impairments that impact a person’s ability to live independently.

Certain groups within the larger population of people experiencing homelessness have different reasons for losing housing. There are nonprofits with targeted missions that approach these groups: survivors of domestic violence, survivors of human trafficking, parents and school age children, and transition age youth (TAY), young people between the ages of 18 and 24.

One of the organizations that helps transition age youth is Social Advocates for Youth (SAY), a Santa Rosa-based nonprofit that helps TAY throughout Sonoma County. Susan Boyle, communications and marketing manager for SAY, says youth are often unlikely to take a bed at an adult shelter.

SAY makes efforts to change the perception that housing is not the only service that transition age youth require. A young person who has been experiencing homelessness for any amount of time needs supports in place to help them thrive.

“These include job skills training, mental health support, access to affordable long-term housing and individualized case management. Many of our youth haven’t had strong role models to teach them skills that adults take for granted,” says Boyle.

Supporting younger children involves efforts by schools and is supported through funding from the state, says Debra Sanders, foster and homeless youth education project coordinator for the Sonoma County Office of Education. It is beneficial for schools to make classrooms sanctuaries, with ample resources like school supplies and food. Teachers can also develop clear, consistent routines which do a great deal to help students feel safe and supported.

“Removing the unknown really helps students who may be sleeping on a relative’s couch or in a family shelter or hotel room,” says Sanders. “These students may be experiencing additional stress such as being afraid they will have to leave suddenly and their belongings could be thrown out.”

One of the big changes that has helped TK-12 students is the state’s provision of free and reduced-priced meals to all students, which most often includes both breakfast and lunch. When the COVID-19 pandemic began, schools began providing meals to all students, regardless of income. This practice has continued, making it easier for students to get food and focus on learning.

Assisting people who are experiencing homelessness and have a severe mental illness (SMI) requires developing an understanding of what each individual needs.

“A mental illness affects how a person thinks, behaves and feels. When mental illness is left untreated, a person with SMI can become very difficult to live with. [This] can push families to the brink. A person with SMI cannot always live peacefully with family members,” says Walsh.

Education around mental illness for family members helps them better understand and communicate with relatives with SMI. NAMI classes and support groups guide a parent or sibling on how to support, access resources and prepare for a crisis.

An important shift that occurred recently is that Medi-Cal is now requiring that treatment for people with co-occurring mental illness and a substance use disorder tackle both at the same time, rather than one before the other.

During the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, one of the programs that benefited people with SMI was Project Roomkey , a state program that lasted from March 2020 to February 2023. Project Roomkey funded placement of individuals who were experiencing homelessness in hotel rooms. The program reduced the spread of COVID-19, which can infect many people in a congregate shelter. Project Roomkey also helped many people with SMI become accustomed to living on their own. Yet people with SMI who are now experiencing homelessness are in need of supportive services.

“Supportive services assist people with SMI with retaining housing by providing practical resources, skill building and relational connections in the community,” says Hernandez.

Lauren Taylor is director of resident services for Burbank Housing, a Santa Rosa-based nonprofit that builds affordable housing in Sonoma and Napa counties. She says Project Roomkey has evolved into Project Homekey, a state-funded effort to add more units of affordable housing. Burbank Housing is building affordable housing with funds from Project Homekey and state funds from the No Place Like Home Program , a PSH program for people in need of mental health services who are experiencing homelessness or at risk of chronic homelessness.

“Across Sonoma and Napa counties, we have three Homekey projects that are now operational: Studios at Montero in Petaluma and Valley Lodge and Adrian Court in Napa,” says Taylor. “Additionally, we recently celebrated the opening of Caritas Homes in Santa Rosa, which was in part supported by No Place Like Home. No Place Like Home is also contributing toward the development of Heritage House Valle Verde in Napa.”

Heritage House Valle Verde is equally split between permanent supportive housing—or, supporting individuals who have been chronically homeless—and traditional affordable housing. Taylor says there are two more projects in the pipeline that include PSH units.

“All PSH units are supported by city or county housing vouchers. It would help if there were more vouchers so we could house more people,” says Taylor.

She adds that since the pandemic started, residents in permanent supportive housing and traditional affordable housing have expressed a higher need for basic resources like food.

“We’ve had to greatly expand our services because wages and government payments for benefits have not kept pace with inflation. The gap places people who want to remain housed at risk, even with affordable rents or vouchers,” says Taylor.

Still, the environment in permanent supportive housing communities benefits residents who focus on becoming stable and remaining housed. Joel Rutkowsky is a resident of The Studios at Montero. He says having a self-contained room with a kitchenette, bed, shower and supportive staff is a vast improvement on living in an encampment or congregate shelter.

“For the most part, everyone here has good intentions. They try to make the most of their life and not get others involved in drinking and drugs. That helps me so much,” says Rutkowsky.

Legislation could reshape the landscape

In 2024, politics will affect what nonprofits can accomplish, potentially by providing funding.

The Bay Area Housing Finance Authority (BAHFA), a new regional agency to advance housing affordability in the nine counties of the Bay Area, anticipates placing a $10 to $20 billion regional housing bond on the November 2024 ballot. If passed, the bond would provide funding to every county and major city in the region to build more affordable housing. It would also create the ability of BAHFA to fund regional housing on an ongoing basis.

Using one-time grant funds, BAHFA is currently launching pilot programs in anticipation of future funding. One of these programs is a homelessness prevention pilot program that will be administered by Housing and Homeless Services of Napa County.

“This program will provide shallow rental subsidies for seniors at risk of homelessness,” says Irene Farnsworth, anti-displacement program coordinator for BAHFA.

In March 2024, Proposition 1, a revamp of California’s Mental Health Services Act, will be on the ballot. If approved, Prop. 1 would create $6.38 billion in bonds to build over 11,150 new behavioral health beds and housing. This would benefit individuals with both substance-use issues and severe mental illness, at risk of homelessness.

Yet Prop. 1 could also mean the reduction of funds for education, prevention and awareness efforts regarding mental illness.

Five signs someone needs help and how to give it

- The person is skipping meals and has significantly cut grocery spending. Share information about local food banks, nonprofits and centers of worship that offer food. Also share personal experiences of getting food assistance to let the person know it is common and you have been through it as well.

- The person is chronically late on rent. Let the person know they can apply to the county housing authority’s voucher program. Also let them know that some nonprofits, such as Catholic Charities, will provide rent assistance, while others, such as the local legal aid office, will help with fighting an eviction.

- The person is not showering and does not have clean clothes. Let the person know about nonprofits like Sonoma Overnight Services that offer shower and laundry services. Sometimes these nonprofits also offer additional clothing.

- The person is depressed, worried, or not sleeping well. Let the person know about the county’s mental health services and nonprofits like Lomi Psychotherapy Clinic, which provide low-cost mental health services. Also let them know that signing up for Medi-Cal and choosing a health care provider will make them eligible for free or low-cost mental health services.

- A child or the child’s friend, neighbor, or classmate indicates the child is concerned about losing or recently lost their housing. Share information with the child’s older teen or adult siblings, parent or guardian about housing resources available in the child’s county of residence, including housing vouchers and rental assistance.—Jessica Zimmer