Anxiety over 'guilt tipping' has reached a breaking point.

Tipping is a simple idea: you’re giving additional money to a service person because they provided above-average service, typically as a percentage of your bill. Bartenders, food service and delivery people, cabbies—even exotic dancers—all rely on tips to a greater or lesser degree.

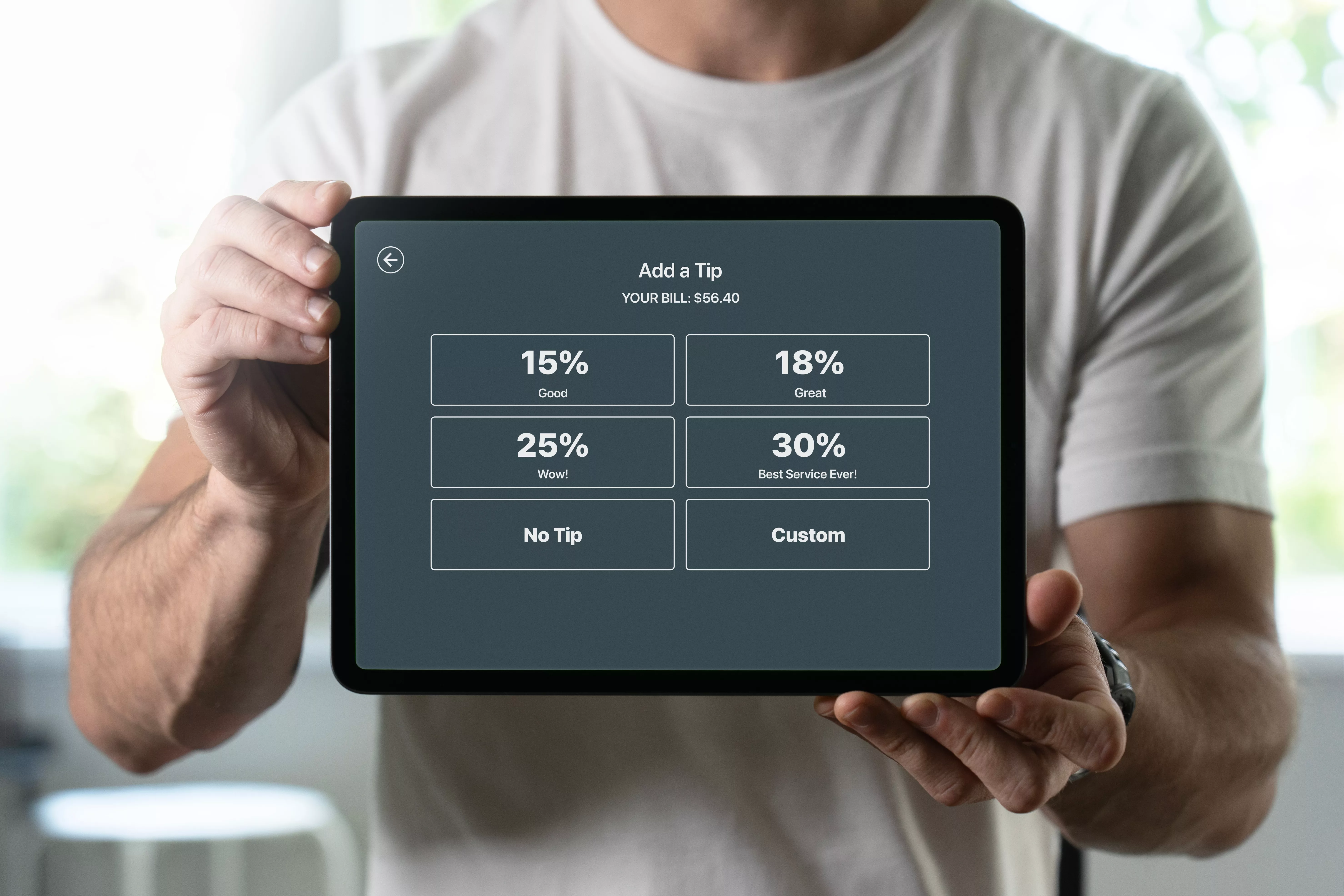

With the spread of point-of-sale (POS) technology, however, we’ve all become painfully aware of tipping: No tip? 15%? 20? 25? Custom? All while the service person who will receive that tip looks on. It’s a surefire way to create anxiety at the point of sale. There’s even a phrase for it: “guilt tipping.”

According to a Pew Research Center report from last November, 72% of Americans think tipping is expected in more places than it was five years ago. Credit card processor Square reports that nearly 75% of remote transactions in food and beverage now ask for a tip. That includes orders online and at kiosks. Pew also notes that about two-thirds of people are confused about when and how much to tip.

Forbes magazine notes that “the pandemic contributed to tipflation, as many people were tipping more generously to support service industry workers who were struggling financially. These were the frontline workers who shopped for our groceries and delivered meals to our homes through apps.” I certainly can attest to the fact that the pandemic increased both the amount and frequency of my own tipping.

But tipping is not as simple as it might seem. In California and 12 other states, tips don’t count as part of an employee’s wages. Seven of those states also have a state minimum wage above the Federal minimum of $7.25 an hour—in California, it’s $16 an hour as of this year. In other states, tips count toward the minimum wage, basically subsidizing the employer for anywhere from $1.25 (Hawaii) to as much as $11.37 an hour (that’s in Maryland, where the state minimum wage is $15 an hour, and the minimum wage for tipped employees is $3.63).

As you might expect, employers like that subsidy. The alternative, of course, would be to eliminate tips and simply pay people more, increasing prices to cover some or all of the increased expense. Many employers feel that this would negatively, perhaps catastrophically, impact their business. And the fact is, tipping culture in America runs deep. Customers like rewarding a job well done, and workers who provide exceptional service like being rewarded for their efforts.

There’s also the issue of what actually happens to your tip. It doesn’t necessarily go only to your server. Tip pooling, where all tips are pooled and distributed according to a formula (set by the employer) among employees, is legal in California. When my daughter worked at the now-defunct Zazu Kitchen in Sebastopol, the server actually only received 50% of the tip amount. The remaining half was split between bartender, barback, busser, host, and back-of-house staff (cooks and dishwashers). Some customers don’t like tip pooling because it rewards both good servers and bad ones equally. As the saying goes, it’s complicated. And every state and employer is different. It’s not surprising that two-thirds of us grapple with tipping.

In the midst of all this confusion. I’d like to make a modest proposal for business owners. If you ask customers for tips as part of your payment process, let your customers know how tips work in your business. They have a right to know what happens to their money. Possible places for this information: the menu, a small card accompanying the bill, on the email receipt you send.

And for tippers, if the POS tipping setup at an establishment bothers you, let them know. Companies like Square and Toast, which together represent over 50% of the POS market, won’t change unless businesses who use their systems complain. I can assure you, these systems have been designed to generate tips (and it appears they work). To its credit, Toast has a pretty good overview of restaurant tipping practices (designed to educate their POS customers). You can read it at tinyurl.com/w3z3jc4k.

For me, it’s pretty simple. If you have a good experience, tip more than any expected minimum (google “US tipping practices 2024” for suggestions). If you can afford it, tip some even when it’s optional. My experience is that regular customers who tip well are well-served by the establishments they frequent. For all its aggravation, tipping appears to work. And, frankly, I feel better when I tip.

What do you think of tipping in the 21st century? Send your thoughts to mike@mikeduffy.com, and I’ll summarize in a future column.

In case you were wondering: I’m still working on my “year of health.” I’ve lost about 15 pounds so far, but I’ve had trouble keeping up with a pound-a-week rate of loss. Tracking my weight on a spreadsheet makes it (depressingly) obvious that I did really well in Dry January, and less well since. So, as I write this in late spring, I’m taking on a Dry May to get back on track. I’ll let you know how it went next month.

Author

-

Michael E. Duffy is a 70-year-old senior software engineer for Electronic Arts. He lives in Sonoma County and has been writing about technology and business for NorthBay biz since 2001.

View all posts