"The superior man is the providence of the inferior. He is eyes for the blind, strength for the weak, and a shield for the defenseless. He stands erect by bending above the fallen. He rises by lifiting others." —Robert Green Ingersoll

Emil Kakkis, M.D., PhD, is a medical geneticist on a mission: To help as many patients with rare and ultra-rare diseases as he can by developing therapies that will save their lives. By all accounts he’s doing whatever it takes to put patients first while also overseeing a fast-growing company that may have as many as 400 employees by year’s end.

Emil Kakkis, M.D., PhD, is a medical geneticist on a mission: To help as many patients with rare and ultra-rare diseases as he can by developing therapies that will save their lives. By all accounts he’s doing whatever it takes to put patients first while also overseeing a fast-growing company that may have as many as 400 employees by year’s end.

What began as an underfunded research project for Kakkis more than 20 years ago has morphed into a major pharmaceutical developer with thousands of square feet of office space in Marin County and Brisbane. Now a public company with a market value of $2.6 billion, Kakkis’ 6-year-old Ultragenyx Pharmaceutical is traded on the Nasdaq under the symbol RARE. The company has several promising treatment therapies for rare diseases in clinical trials and a couple inching toward approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (see “Life-Saving Treatments in the Pipeline,” page ??).

Rare diseases are defined as those with fewer than 200,000 patients in the United States; a ultra-rare disease reports fewer than 6,000 cases, says Kakkis. The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development states that roughly 80 percent of rare diseases are genetic, and about one-half of all rare diseases affect children. Of the 7,000 rare diseases identified by the Centers for Disease Control, only 289 have an approved treatment.

According to the EveryLife Foundation for Rare Diseases, the average rare disease patient will be examined by eight doctors, misdiagnosed three times and wait more than seven years to receive the correct diagnosis. About 30 percent of rare disease patients will not live to celebrate their fifth birthday.

Biochemistry plus management

Born in Montebello in southern California, Kakkis grew up in Long Beach, where his father, Albert, was a neurologist at St. Mary’s Medical Center. “All of my early exposure to medicine was through my father. I spent a fair amount of time in his work environment,” he explains. “My father was gregarious and engaging, but I didn’t feel I was quite that same person.” Lab research was a better fit for the younger man.

Now 56, Kakkis says he was “no longer in training, technically” by the time he reached age 33. “First there was college, then medical school, then my pediatrics training, medical genetics fellowship and my first job as an assistant professor. All that training, however, put me in a position to combine biochemistry and management.”

During his career, Kakkis developed numerous drug treatments for rare diseases, with some gaining FDA approval while he worked at BioMarin Pharmaceutical. On the market since 2003, Aldurazyme is an enzyme replacement therapy for the rare genetic disease mucopolysaccharidosis I (MPS I). The therapy was authorized for use in Europe the same year and is now available in more than 70 countries.

At BioMarin, Kakkis guided the development of other therapies for rare diseases, including Naglazyme for MPS VI and Kuvan for phenylketonuria (PKU), a metabolism disorder in which certain enzyme activity is absent in the body. Both were approved by the FDA.

A major breakthrough

A major breakthrough

Aldurazyme was born in an old military Quonset hut behind Harbor-UCLA Medical Center in Torrance, where Kakkis began his first significant research in the mid-1990s. “It had a low ceiling and just one computer—the kind of place you’d never dream a therapy breakthrough could take place,” recalls Mark Dant, father of MPS I patient Ryan Dant, who was missing a crucial enzyme that his cells needed to break down sugar.

In 1991, when Ryan was diagnosed with MPS I in Texas at age 3, his parents left no stone unturned trying to save their son’s life. Children diagnosed with the disease at that time weren’t expected to live beyond their teens. Profound physical changes would take place before death, including blindness, deafness and mental deficiencies. There was no known treatment or cure.

MPS I is one example of an “orphan” disease, a condition so rare that sponsors are reluctant to develop the “orphan drugs” to treat them. Orphan drugs are pharmaceuticals that remain commercially undeveloped because of their limited potential for profitability.

“We would ask Ryan’s physicians, ‘Who’s working on treatments for this?’” says Mark. “One doctor told us MPS I is a disease no one’s heard of, and drug companies won’t step up to work on things like it because it’s so rare.”

Dant and his wife read everything they could about MPS I and began searching for scientists who were seeking treatments for it.

Funding research

Dant, a police officer, bought a book on how to start a nonprofit organization and raise funds. That led to a modest bake sale that collected $342 for MPS I research. The Dants continued their quest for scientists working specifically on treatments for MPS I and started their own nonprofit, the Ryan Foundation. Small fundraisers turned into golf tournaments and brought in more dollars. All funds were sent to the National MPS Society, an organization for families living with the disease.

Meanwhile, Kakkis was working tirelessly in the Quonset hut on the enzyme replacement therapy that would later be marketed through BioMarin as Aldurazyme. The late 1980s and early 1990s were exciting times in genetics, he says. “Many genetic diseases were being identified and discovered then.”

By networking at MPS conferences, the Dants heard about Kakkis’ research project from one of his colleagues, Dr. Elizabeth Neufeld, also an MPS researcher. Dant says Neufeld told him, “I have a former student [Kakkis], who’s possibly the most brilliant student I’ve ever had. He’s working on MPS I but has no funds.”

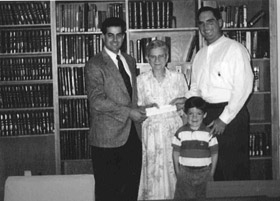

Meeting Kakkis for the first time and presenting him a check for $40,000 to help jumpstart the research was one of the most exciting days of Dant’s life. “I knew in my heart after just one conversation with Emil that he had a drive like nobody I’d ever met,” he says. “My wife and I decided right then we’d help him raise funds for his research any way we could.”

A few years later, the compelling story of the Dant family and their special relationship with Kakkis attracted the attention of 60 Minutes, which aired a segment about Kakkis’ research and how Ryan Dant was surviving and thriving by receiving regular treatments of Aldurazyme in clinical trials. Their story was also featured in an issue of Reader’s Digest in 2001.

Ryan finished high school (Kakkis attended the graduation in Dallas with the Dants) and now, at age 28, he’s attending the University of Louisville on a full scholarship and works on the football team’s equipment staff. He continues to receive enzyme replacement therapy.

“I don’t know if Emil understands how different a doctor he really is,” says Mark Dant, who recently retired from law enforcement and is now the executive director of the National MPS Society. “He’s always focused on the patient. Others may say that, but Emil lives it.”

80-hour workweeks

80-hour workweeks

Kakkis has an impressive track record of developing treatments and getting them approved, says Julia Jenkins, executive director of the EveryLife Foundation for Rare Diseases, which was started by Kakkis in 2009 to accelerate biotech innovation for rare diseases. “But he always sees it as, ‘I could have done more if not for the roadblocks in the regulatory process.’ Working full-time to him is 80 hours per week,” she says. “If the parent of a newly diagnosed child calls and needs advice, that’s his first priority. He always takes their calls and returns their emails. He’ll still be returning emails at midnight. It’s a huge passion of his to help the patients.”

EveryLife’s mission is to save lives by changing policy, specifically to improve and accelerate drug approval processes through its Cure the Process campaign. “We focus on improving the regulatory processes,” says Jenkins. Last year, the foundation introduced into Congress the OPEN (Orphan Products Extension Now) Act, to repurpose drugs for rare diseases. It passed in the House and is pending in the Senate. “This legislation could bring hundreds of safe, effective and affordable medicines to rare disease patients within the next several years by incentivizing drug makers to repurpose therapies [meaning they would run a new clinical trial to test a medicine’s efficacy in treating a disease or condition for which it wasn’t originally developed] for the treatment of life-threatening rare diseases and pediatric cancers,” says Jenkins.

EveryLife also has legislation pending in California (SB 1095) that would expand the health screening of newborns. “There’s so much need in the rare disease community,” she adds.

Kakkis has stepped down from day-to-day operations at EveryLife Foundation, but he remains its president and best resource for scientific and regulatory drug development expertise, says Jenkins. “It’s next to impossible to hire someone with an M.D. and a PhD who’s also had drugs approved. Emil would be very difficult to replace.”

Looking for defects

Kakkis joined BioMarin in 1998, and left 10 years later to start the EveryLife Foundation. He launched Ultragenyx in 2010. “It was just me and an executive assistant at first,” he says. Two years later, there were 24 employees; 59 employees worked at the company when it went public in January 2014. Today, there are more than 300 employees.

“We invested $2 million in the first year of Ultragenyx and have been able to raise more than $500 million in capital to invest in the research of new rare diseases,” he says. “And now, it’s remarkable that we’re working on treatments for 10 different rare genetic diseases at the same time.”

More than half of Ultragenyx’s employees handle clinical development work, designing and running the clinical trials conducted at hospitals worldwide, explains Kakkis. The remaining employees are involved in research, manufacturing, quality, compliance and general and administrative functions.

“What we do in our facilities is the intellectual work—the designing and planning and management of the business aspect of running the drug trials,” says Kakkis. “The hard, wet research takes place in labs around the world, including here in Novato at the Buck Institute for Research on Aging. We work collaboratively to use its first-rate facility.”

The working culture at Ultragenyx, says Kakkis, is based on a passionate commitment to get patients treated. “We started this company to take on diseases nobody else was looking at. Our business model is to look for patients whose bodies have a defect. We take what’s wrong, pick a compound and put it into development, basically making a replacement therapy for them. With genetic diseases, we know exactly what’s wrong, so we develop a better way to treat it. Our identity is defined by five words––courageous, generous, dynamic, relentless and possibility.”

Life-Saving Treatments in the Pipeline

Life-Saving Treatments in the Pipeline

Ultragenyx, the pharmaceutical company founded by Dr. Emil Kakkis, is developing several treatment therapies for rare diseases currently in different phases of clinical trials. Some are in late-stage development, and Kakkis expects to file for FDA approval of two of these medications within the year.

Biologic drugs in development include:

• KRN23 for treating X-linked hypophosphatemia (XLH), a bone disease characterized by phosphate-wasting due to excess activity of FGF23, a hormone that reduces serum levels of phosphorus and vitamin D (approximately 12,000 patients in the United States); and for tumor-induced osteomalacia (TIO), a disease characterized by typically benign tumors that produce excess levels of FGF23, including its skin lesion variant, epidermal nevus syndrome (500 to 1,000 U.S. patients).

• rhGUS for treating mucopolysaccharidosis 7 (MPS 7), a genetic metabolic disorder caused by a deficiency of the lysosomal enzyme beta-glucuronidase, which is required for the breakdown of certain complex carbohydrates (200 patients in the developed world).

• rhPPCA for treating galatosialidosis, an enzyme deficiency that results in accumulation of substrates in the lysosomes, causing skeletal and organ dysfunction, and death (300 to 500 patients in the developed world).

Small molecule drugs in development include:

• UX007 for treating fatty acid oxidation disorders (FAOD), in which the body is unable to convert long-chain fatty acids into energy (2,000 to 3,500 U.S. patients); and glucose transporter 1 deficiency (Glut1 DS), a severely debilitating disease characterized by seizures, developmental delay and movement disorders (3,000 to 7,000 U.S. patients).

• Aceneuramic acid for treating GNE myopathy (GNEM), a rare, severe, progressive, genetic neuromuscular disease caused by a defect in the biosynthetic pathway for sialic acid, with onset usually after age 20 (2,000 patients in the developed world).

Charisma and Clooney

“Emil is a charismatic guy,” says Ultragenyx’s CFO, Shalini Sharp. “He’s great with our investors, and people love talking to him. He’s genuinely trying to do something good in the world, and when you work with him you feel like you’re part of that. It gives our work meaning.”

The Emil Kakkis story is so amazing, says Mark Dant, “there should be a movie made about him—honestly.” George Clooney in the role of Kakkis, he adds with a chuckle, would be great casting.

Music, Art and Baklava

Dr. Emil Kakkis may put in long hours on the job, but colleagues also get to see his lighter side. “Emil told us once that his mom had the best recipe for baklava,” says Mark Dant. “So once when we were visiting his house in San Rafael, he gave us a lesson in how to make it. It was a classic Emil moment––here’s this great scientist, who’s literally saved hundreds of lives, and he’s sharing his mother’s recipe. He’s just a sincerely kind and gentle person.”

Married 32 years, the couple has raised three children––a son nearing graduation from college, and twins (a son and a daughter) who just graduated high school. Kakkis plays the piano and so do his children. “They’re a very musical family and really down to earth,” says Julia Jenkins, executive director of the EveryLife Foundation.

The Kakkis family usually hit the slopes at Lake Tahoe every winter, and also goes scuba diving together (Kakkis is certified). “I’m pretty good at ocean fishing, too,” he adds. “I’ve been fishing since I was little. I go to Mexico for tuna, and to Alaska. I’m trying to sample fishing in more places around the world.”

Jenkins says Kakkis has a huge passion for music and art. “For Emil, science and art are very connected, and both are important to him.” When the Youth in Arts Italian Street Painting Festival in San Rafael was being discontinued five years ago because of a lack of funding, Kakkis stepped forward to bring it back. “He pledged $20,000 and worked to get additional pledges to keep the festival going. The Italian Street Painting Marin event is now part of EveryLife’s community outreach program,” she says. “The foundation also has a program for patients and their caregivers who are artists, and we hold receptions for them throughout the year.”