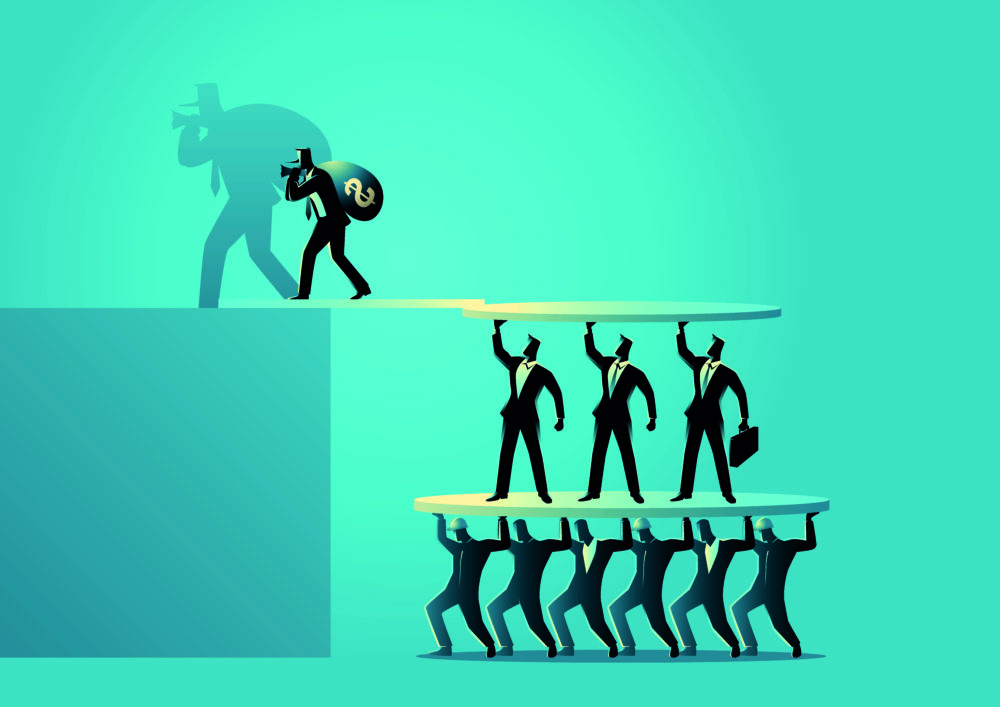

To make a Ponzi scheme work properly, you need an idea to sell, a pipeline of fresh investors, and the proper profile—high enough to generate quality word of mouth, but low enough to avoid unwanted attention from those who could topple the arrangement.

From 2015 to early 2020, Novato’s Professional Financial Investors Inc. fit that description beautifully, according to a lawsuit by the Securities and Exchange Commission, as well as a criminal action filed by the U.S. Justice Department in federal court. Both actions were filed in San Francisco in late September.

The company focused on acquiring apartment houses and commercial real estate and was led by Kenneth Casey and Lewis Wallach. Professional Financial owned about 70 properties in Marin and Sonoma counties. Investors wrote checks that went into a pooled fund so that the company could purchase real estate assets, and received returns based on the performance of the buildings. In theory, the proceeds would be derived from lease revenues, interest on cash waiting to be invested and sale proceeds when buildings were sold.

But a Ponzi ploy don’t really work that way. Early investors are paid with later investors’ cash. And of course, the trick is keep a steady flow of fresh investment cash coming in, while delaying payment to earlier investors if the cash pool is short. The trouble is, at some point, the pipeline of fresh cash slows down, and the ruse begins to look like a game of musical chairs as the organizers scramble to cover payments.

The other part of the Ponzi manual calls for the folks running the scheme to skim cash off the top for their own uses.

The most famous Ponzi example is the one operated by Bernie Madoff in New York, which claimed 4,800 victims who lost about $65 billion. Madoff pled guilty in March 2009 and was sentenced to 150 years in the slammer with a fine of $150 billion.

In the case of Professional Financial, the 64-year old Wallach carved out $26 million in profits from $350 million that was raised from investors, many of whom were seniors reliant upon the returns from the investment to pay for their expenses in retirement.

Wallach allegedly used investor cash to pay for a second home in Malibu, luxury wheels and real estate investments in Texas and Northern California that went bad as well as payments on his credit cards.

Casey, 73, died in May of a heart attack.

One of the biggest qualities a Ponzi plot needs is adequate social cover. Casey was a member of the Marin Human Rights Commission from 2015, a cruel bit of irony. Another ability Ponzi operators need is to have an answer for every question, and when worried investors came calling this spring in the midst of COVID-19 asking about Professional Financial Investors’ ability to weather the storm and the safety of their investments, they were told by Casey and Wallach that company’s reserves were adequate protection.

But the investors were right to inquire, especially given Casey’s backstory. He founded Professional Investors in 1990 and was charged with 53 counts of fraud and tax offenses in 1998. At the time of the conviction, he was a certified public accountant, and he lost his license as a result of the settled charges.

Arguably, those charges should have tipped off investors, but not everyone is adept at due diligence. Wallach joined Casey in 1990 as an accountant and became president in 1998, and the two moved forward with recruiting Professional Investors’ victims.

The SEC is very seldom the first on the scene of a swindle, and this case is no exception. The regulator became aware something was wrong after Casey died and his ex-wife, Charlene Albanese, the beneficiary of Casey’s estate, reached out through a law firm to say that something was amiss. Not long after that, the DOJ and the FBI began a criminal investigation.

Wallach has already admitted to the civil charges and pled guilty to the criminal charges. He faces a possible sentence of 20 years in federal prison on each count and a fine of $250,000, along with additional, yet to be determined, monetary damages. A Dec. 28 hearing is set for sentencing.

The SEC filing said that Wallach had returned $1 million in cash and was moving to transfer ownership of his homes to the company.

In July, Professional Investors filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy status as the properties owned by the company were worth about $550 million and the company carried $650 million in debt. Between the SEC charges, the DOJ case and the bankruptcy filing, it is difficult to know what investors can expect to recover.

Author

-

Bill Meagher is a contributing editor at NorthBay biz magazine. He is also a senior editor for The Deal, a Manhattan-based digital financial news outlet where he covers alternative investment, micro and smallcap equity finance, and the intersection of cannabis and institutional investment. He also does investigative reporting. He can be reached with news tips and legal threats at bmeagher@northbaybiz.com.

View all posts